Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Bob Colegrove, who writes:

Hi Thomas,

I came across this article on Wikipedia. It is a few days late, but thought it might be of interest to others. The link is

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_American_Regional_Broadcasting_Agreement.

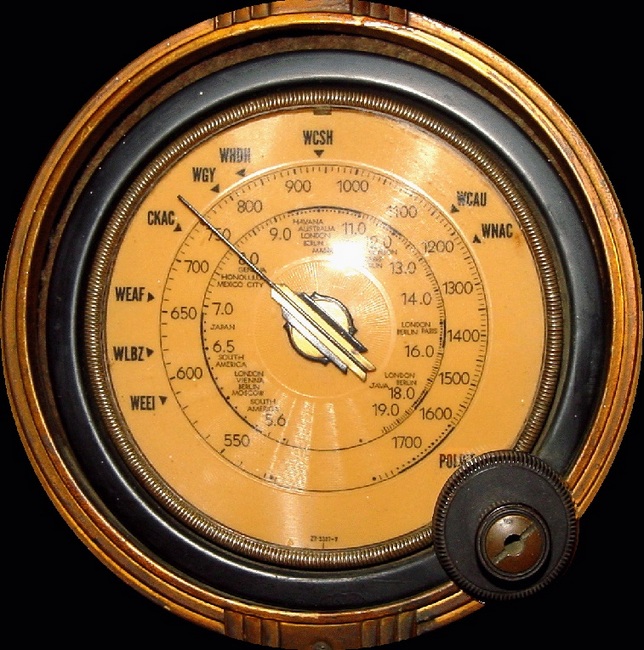

Briefly, this past Monday, was the 80th anniversary of the implementation of the “Havana Treaty,” which was actually signed on December 13, 1937, and finally implemented 80 years ago on March 29, 1941. It provided for reorganization of the “AM” medium wave band into frequency allocations for clear channel, regional and local stations.

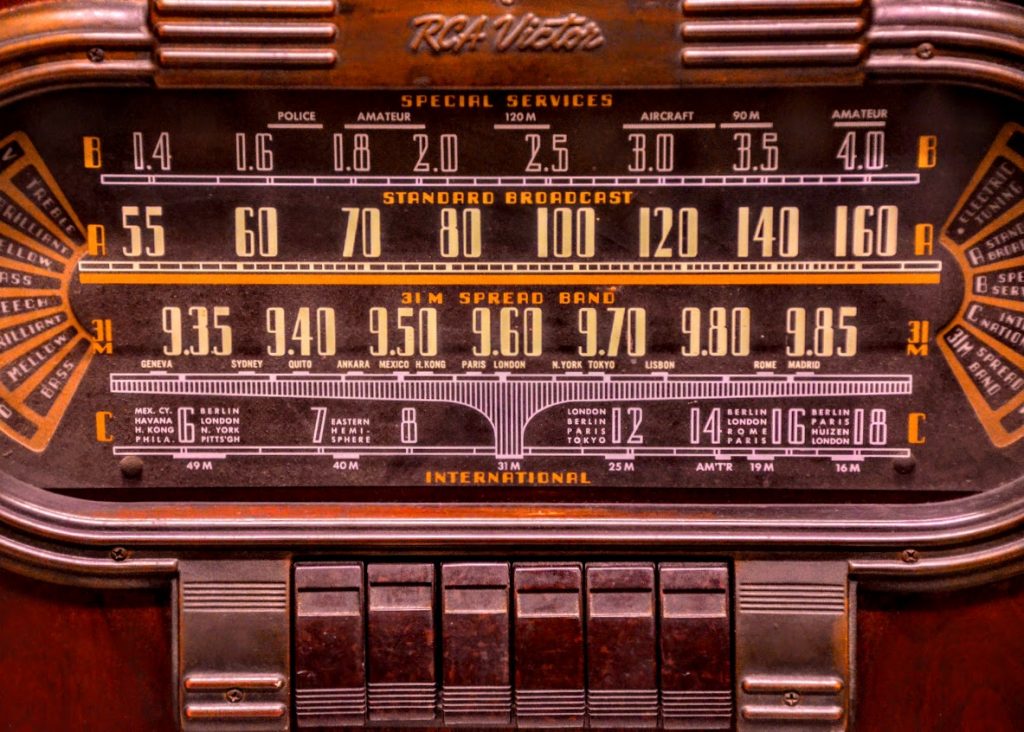

AM radio was the Internet of its day. The invention of the telegraph notwithstanding, radio provided widespread, instant communication, albeit one way, to a vast population reaching hundreds of miles from the transmission source. It extended to the most rural parts of the country adding “A battery” and “B battery” to the lexicon.

The initial licensing process had been done with very little planning and forethought using 96 channels between 550 and 1500 kHz. The reorganization was the culmination of the need for some order to reduce mutual station interference and provide more reliable service to listeners. It involved frequency changes for about 1000 stations in several countries. March 29, 1941 was informally known as “moving day.”

The Wikipedia article details the changes made at that time and goes on to describe subsequent expansions of the AM broadcast band.

Fascinating! Thank you for sharing this bit of radio history with us, Bob!