(Source: The Washington Post)

On Aug. 21, as the moon passes in front of the sun and casts a shadow across the United States, millions are expected to gaze at the totality. Meanwhile, a smaller crowd will be glued to 150 custom-made radio receivers set up across the country.

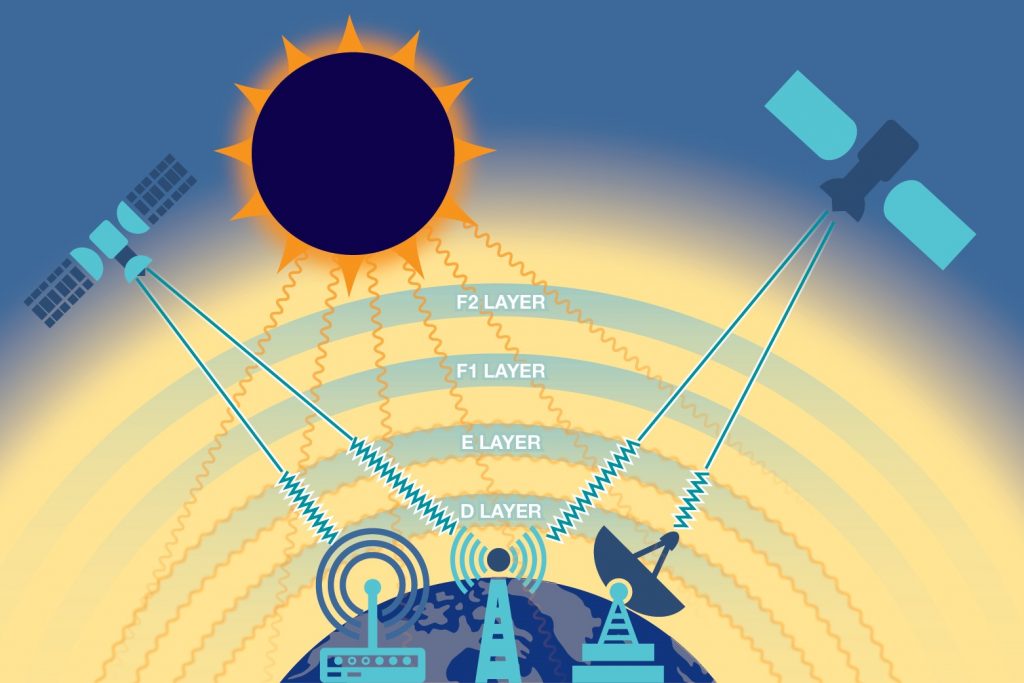

The project, called EclipseMob, is the largest experiment of its kind in history. By recording changes in the radio signal, these citizen scientists will collect data on the ionosphere — the region of the atmosphere where, miles above Earth’s surface, cosmic and solar radiation bumps electrons free from atoms and molecules. It plays a crucial role in some forms of long-distance communication: Like rocks skipped across a pond, radio waves can bounce along the top of the ionosphere to travel farther around the globe. But signals passing through the ionosphere sometimes behave in unpredictable ways, and scientists still have a lot of questions about its properties and behavior.

“Any solar eclipse is a good opportunity to study the ionosphere,” said Jill K. Nelson, an expert in signal processing at George Mason University in Virginia. The level of ions in the ionosphere fluctuates from day to night, decreasing in the absence of sunlight. But this change happens gradually during normal sunrises and sunsets. The sudden light-to-dark switch as it occurs during the eclipse, then, is an opportune moment to observe this layer of the atmosphere.

Many thanks for the tip, Ed!

I have a few recordings during the eclipse and my general observation is that the phenomenon is MUCH stronger as the dark spot (umbra??) travels AWAY from the listener. I had very little success listening to AM/MW radio stations to my west, but amazingly strong signals to my east. I was in Southern Illinois and everything east of me from Tennessee, Atlanta, and North Carolina was BOOMing in and very clear with some pulsing type fading. Not much to my west but I may have heard Casper WY but so faint and buried in noise.