This past Saturday, I found the irony a bit much to take: on one hand, there was Syria, a highly volatile country struggling for stability, while on the other hand, there was…Canada? Both, on the same fateful day, effecting media shut downs.

This past Saturday, I found the irony a bit much to take: on one hand, there was Syria, a highly volatile country struggling for stability, while on the other hand, there was…Canada? Both, on the same fateful day, effecting media shut downs.

No doubt, most every Syrian with Internet access knew their Internet had been shut down this past weekend, while very few Canadians knew that their international radio voice had been quelled. In both cases, the government was mostly to blame, though in Canada the CBC was left holding the knife.

The venerable, yet vulnerable Internet

I’ve mentioned numerous times how vulnerable the Internet is to simply being shut off. In most cases, this happens because those in power are attempting to control free speech and communications. Unfortunately, it’s not an infrequent occurrence; if anything, it’s a growing trend. In this NPR story from Saturday, Andrew McLaughlin, former White House adviser on technology policy, was quoted as saying:

“The pattern seems to be that governments that fear mass movements on the street have realized that they might want to be able to shut off all Internet communications in the country, and have started building the infrastructure that enables them to do that[.]”

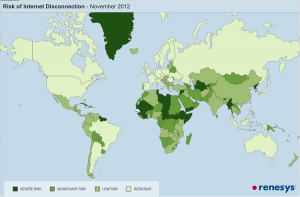

Renesys map showing vulnerable internet networks by country (click to enlarge). Note that most of the countries with low risk are those who have (or had) a strong international broadcasting presence on shortwave.

Not good. And as unethical as it sounds for Syria (or Egypt or Libya or the Maldives or China or Burma) to have shut down the Internet, if the U.N.’s World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT-12) meeting is successful, it will make Syria’s shutdown a legally supported scheme for every country in the world.

So what countries are technically vulnerable to this sort of shut down? It depends to a great extent on the diversity of a state’s communications infrastructure, and the number of its service providers that are connected to the rest of the world. Syria, sadly, is among the most vulnerable. James Cowie, at the Web monitoring firm, Renesys, was recently quoted in the Washington Post describing just how easy this shut-down process is:

“Make a few phone calls, or turn off power in a couple of central facilities, and you’ve (legally) disconnected the domestic Internet from the global Internet.”

Information of last resort

In January of 2011, Egypt, too, shut down its Internet service. Radio Netherlands Worldwide (RNW) responded by adding shortwave broadcasts targeting Egypt. Since then, RNW has been silenced. I would like to think that if RNW, with its once-powerful human rights and free press missions, were still around, the organization would have leapt to the aid of the Syrians. Alas, where are they now?

True, shortwave radio is not a comprehensive replacement for the Internet any more than it is for mobile phone service. It lacks the peer-to-peer connectivity of either medium. But it is interactive and accessible.

Indeed, recent history proves that, when all other communications systems are shut down, information still leaks from a country via various means. This very information is often broadcast by international voices over every medium, including shortwave radio. So there exists an intimate interaction between those living under a repressive regime and the foreign press that is impossible to deny. Shortwave radio is, in a very real sense, an arm of the foreign press and diplomacy, one that still reaches out to the citizens of oppressed countries.

What about satellite?

To be fair, did Egyptians seek out shortwave radio when their country’s Internet went down? Not all, but quite a number did. In truth, satellite TV is king in many growing countries, and the information found on satellite was still flowing freely. Therefore, many turned to satellite.

So is shortwave radio still needed? Of course. Satellite TV, like the Internet, is much easier to jam or block. Shortwave radio is the only broadcast medium that streams at the speed of light across borders with no regard for those in power, that requires no subscription or expensive equipment, and is 100% untraceable (provided you listen through headphones).

I’d like to think that even the UN or similar state networks would consider pooling funds to keep shortwave radio broadcasters on the air to protect this valuable resource. Still, it’s those countries with the wealth, the stability, and the democracy, that feel shortwave is so dispensable. When budgets are being cut, governments view their foreign broadcast service as a quick chop. They don’t realize that an international radio voice is actually the most reliable, most cost-effective arm of foreign diplomacy–especially in areas of the world where information does not flow freely. In such regions, they have a captive audience at pennies a head.

So, who will be next country to shut down their Internet services and leave their citizens in the dark? Follow the headlines. And who will silence the next shortwave broadcaster? Follow the money.