Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Eric McFadden (WD8RIF), who shares the following story from Spaceweather.com (my comments follow):

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Eric McFadden (WD8RIF), who shares the following story from Spaceweather.com (my comments follow):

On Sept. 1st, 1859, the most ferocious solar storm in recorded history engulfed our planet. It was “the Carrington Event,” named after British scientist Richard Carrington, who witnessed the flare that started it. The storm rocked Earth’s magnetic field, sparked auroras over Cuba, the Bahamas and Hawaii, set fire to telegraph stations, and wrote itself into history books as the Biggest. Solar. Storm. Ever.

But, sometimes, what you read in history books is wrong.

“The Carrington Event was not unique,” says Hisashi Hayakawa of Japan’s Nagoya University, whose recent study of solar storms has uncovered other events of comparable intensity. “While the Carrington Event has long been considered a once-in-a-century catastrophe, historical observations warn us that this may be something that occurs much more frequently.”

To generations of space weather forecasters who learned in school that the Carrington Event was one of a kind, these are unsettling thoughts. Modern technology is far more vulnerable to solar storms than 19th-century telegraphs. Think about GPS, the internet, and transcontinental power grids that can carry geomagnetic storm surges from coast to coast in a matter of minutes. A modern-day Carrington Event could cause widespread power outages along with disruptions to navigation, air travel, banking, and all forms of digital communication.

Many previous studies of solar superstorms leaned heavily on Western Hemisphere accounts, omitting data from the Eastern Hemisphere. This skewed perceptions of the Carrington Event, highlighting its importance while causing other superstorms to be overlooked.

[…]Hayakawa’s team has delved into the history of other storms as well, examining Japanese diaries, Chinese and Korean government records, archives of the Russian Central Observatory, and log-books from ships at sea–all helping to form a more complete picture of events.

They found that superstorms in February 1872 and May 1921 were also comparable to the Carrington Event, with similar magnetic amplitudes and widespread auroras. Two more storms are nipping at Carrington’s heels: The Quebec Blackout of March 13, 1989, and an unnamed storm on Sept. 25, 1909, were only a factor of ~2 less intense. (Check Table 1 of Hayakawa et al’s 2019 paper for details.)

“This is likely happening much more often than previously thought,” says Hayakawa.

Are we overdue for another Carrington Event? Maybe. In fact, we might have just missed one.

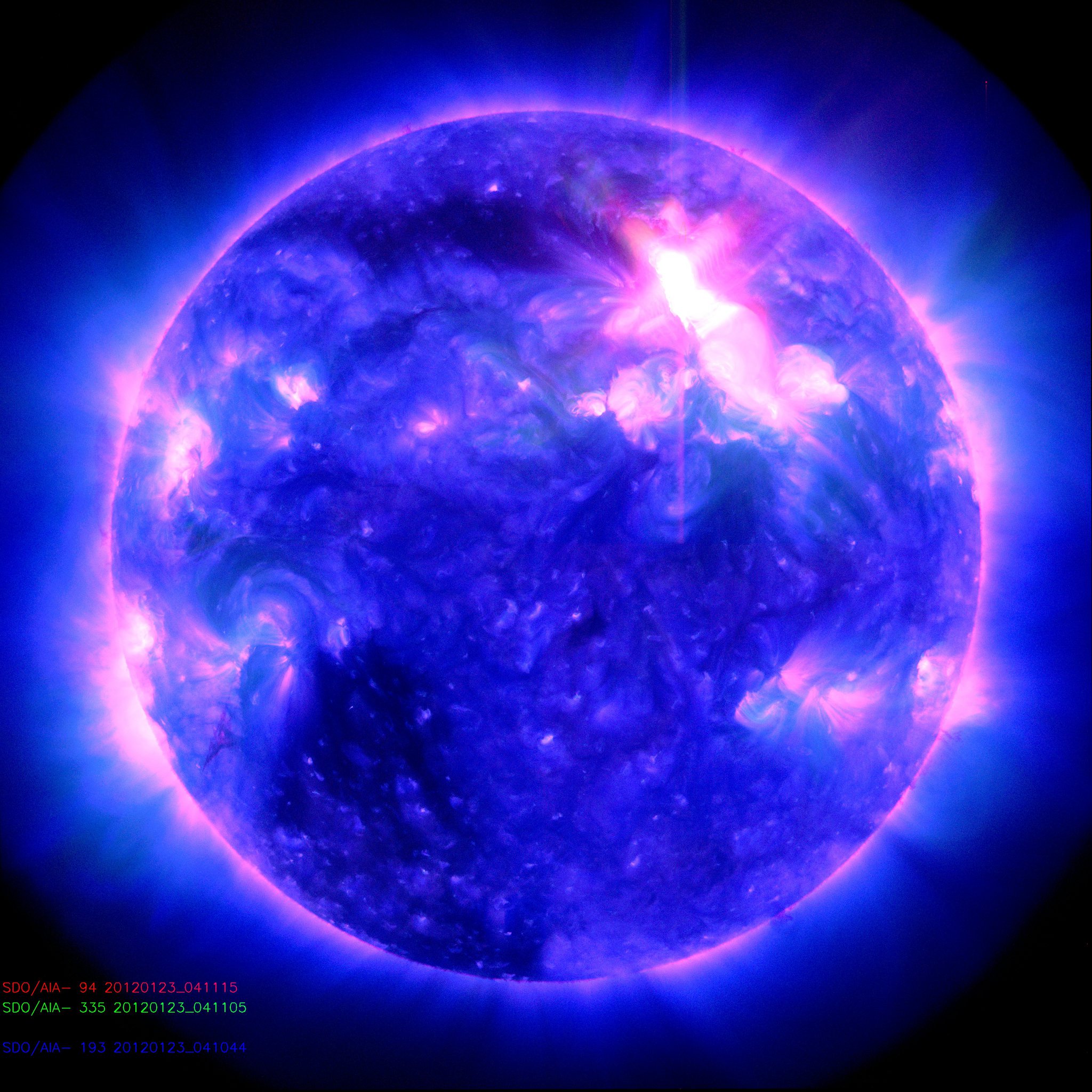

In July 2012, NASA and European spacecraft watched an extreme solar storm erupt from the sun and narrowly miss Earth. “If it had hit, we would still be picking up the pieces,” announced Daniel Baker of the University of Colorado at a NOAA Space Weather Workshop 2 years later. “It might have been stronger than the Carrington Event itself.”

History books, let the re-write begin.

With the way 2020 has gone so far, it might be wise to take a look at our EMP Primer which goes into detail about how to protect your radio gear from an EMP event like this. It’s not an expensive process, but requires advance preparation.

Anyone know what kind of warning we would get- in other words – from the time it is detected by satellite until it hits?

120ms if geostationary TV sats are being toasted in the way, otherwise times that are not perceivable for humans.

That is, In case of a flare hitting us.

I’ve read that we’ll get maybe one day’s notice that it will hit us. If we’re lucky.

Keep in mind that a CME is not an EMP. It won’t damage sensitive electronics, but it will mimic the destructive E3 effects of a high-altitude nuke, taking out the high voltage AC distribution transformers. Your battery operated equipment will be fine, which is good, because you’ll need it!

I was really hoping you’d join this thread, OM!

-Thomas

Keep in mind that most Electrical transmission lines will probably be shut down in advance of a super-flare to protect high voltage switch gear and the transformers. So whatever plans you have to get back on the air should also include a power supply of some sort.

A very good point. In fact, herein lies on of the problems with tube/valve gear: they’re more resilient to EMPs, but also much more difficult to power if the grid is down for an extended period of time.

I’m curious if the Ghz energy from a Carrington-type event is significant enough to damage electronics at ground-level (like an EMP from a nuclear device would be), or if the main danger is from lower frequencies and long wires (antennas & power lines). If it’s the latter, simply unplugging things, or even surge protection, might save most things. Just another reason for standard lightning protection. Buying electronics and storing them indefinitely in shielded bags is definitely not very practical.

Good question. You might want to check out our EMP primer because we had an EMP expert address many of these questions.

In the end, a Carrington type event *could* be more devastating than even a nuclear EMP because of the impact footprint (which could be half the planet) and length of exposure. Possibly the strength of the EMP as well. It’s also my understanding that there are so many variables, we really don’t know what the full impact could be. Probability is something less than fear-mongers would have you believe. I’m with you: storing everything in little shielded bags isn’t terribly practical.

Since I published the EMP primer, I’ve kept a small metal sealed trash can with enough radio gear that I’d be able to get back on the air pretty quickly. It’s essentially a “set it and forget it” supply. I do, on occasion, rotate out some of the supplies (remove one radio and replace with another).

I believe in approaching this in a practical way: low-cost, DIY, and low maintenance. I think it’s just a good insurance plan. With any luck, we may never be affected by such an event, then again the sun has been incredibly active the past decade and launched numerous CMEs. We’ve had close calls. Can’t hurt to be prepared without all the panic and fear, I say. 🙂

Cheers,

Thomas

that’s why some of us keep tubes trx rigs around 😉