Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Don Moore–noted author, traveler, and DXer–for the latest installment of his Photo Album guest post series:

Don Moore’s Photo Album: Bolivia 1985

by Don Moore

After finishing Peace Corps, my ex-wife and I spent six months traveling around South America in 1985. In mid-June we crossed the border to southern Bolivia from Argentina and took an overnight train to the mining center of Oruro. We also visited Cochabamba and the capital of La Paz before heading to Peru ten days later. We would have stayed longer but 1985 was the worst year ever for Bolivia’s typically unstable economy and the country was being wracked by labor strikes and food shortages. But I did manage to visit about a dozen Bolivian shortwave stations.

Photos

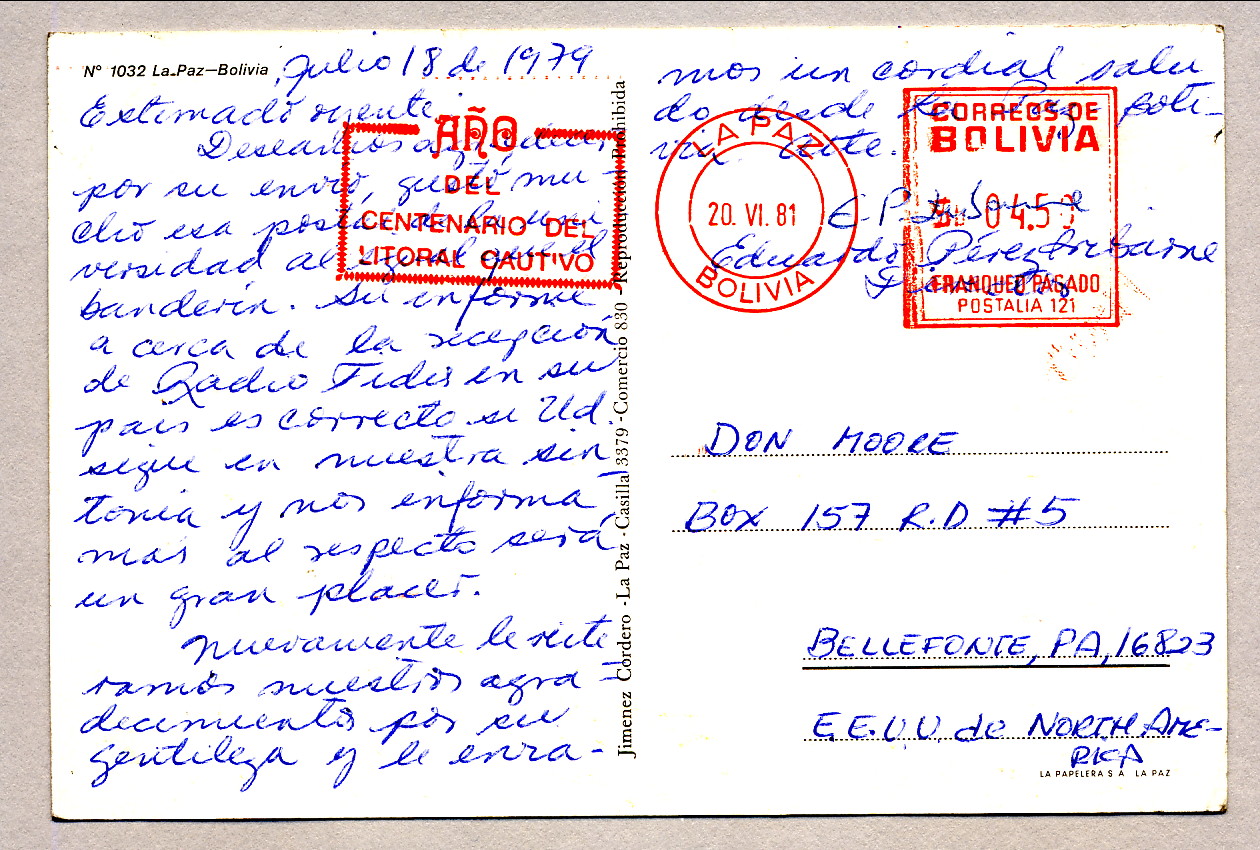

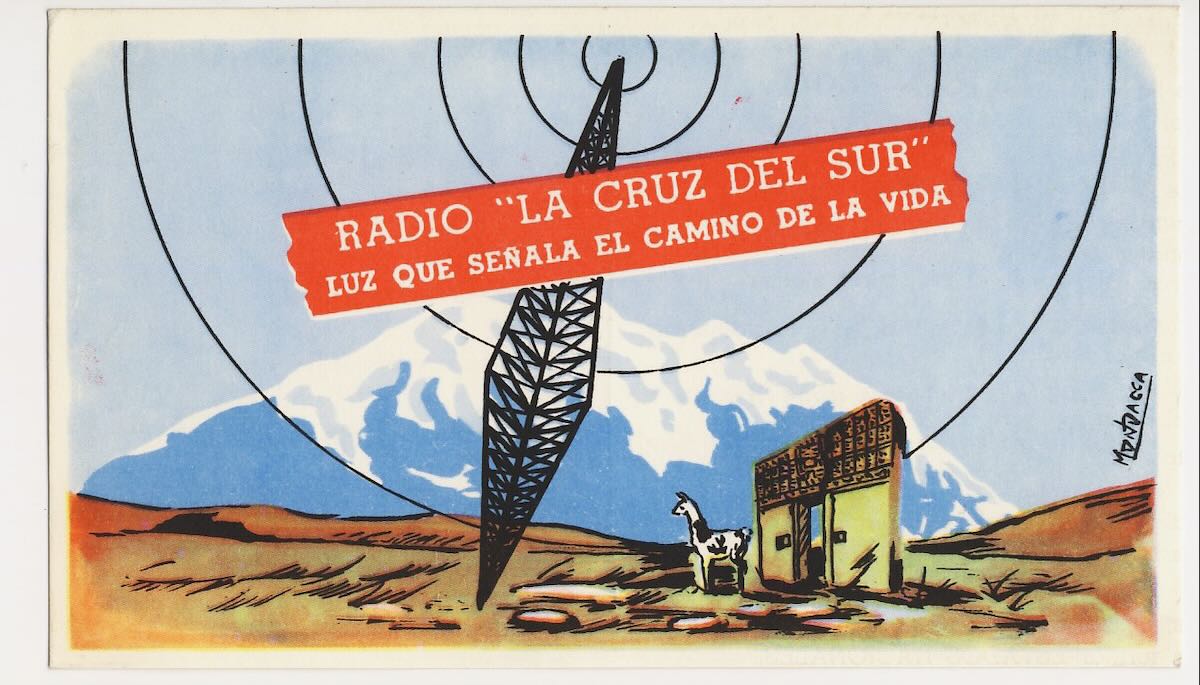

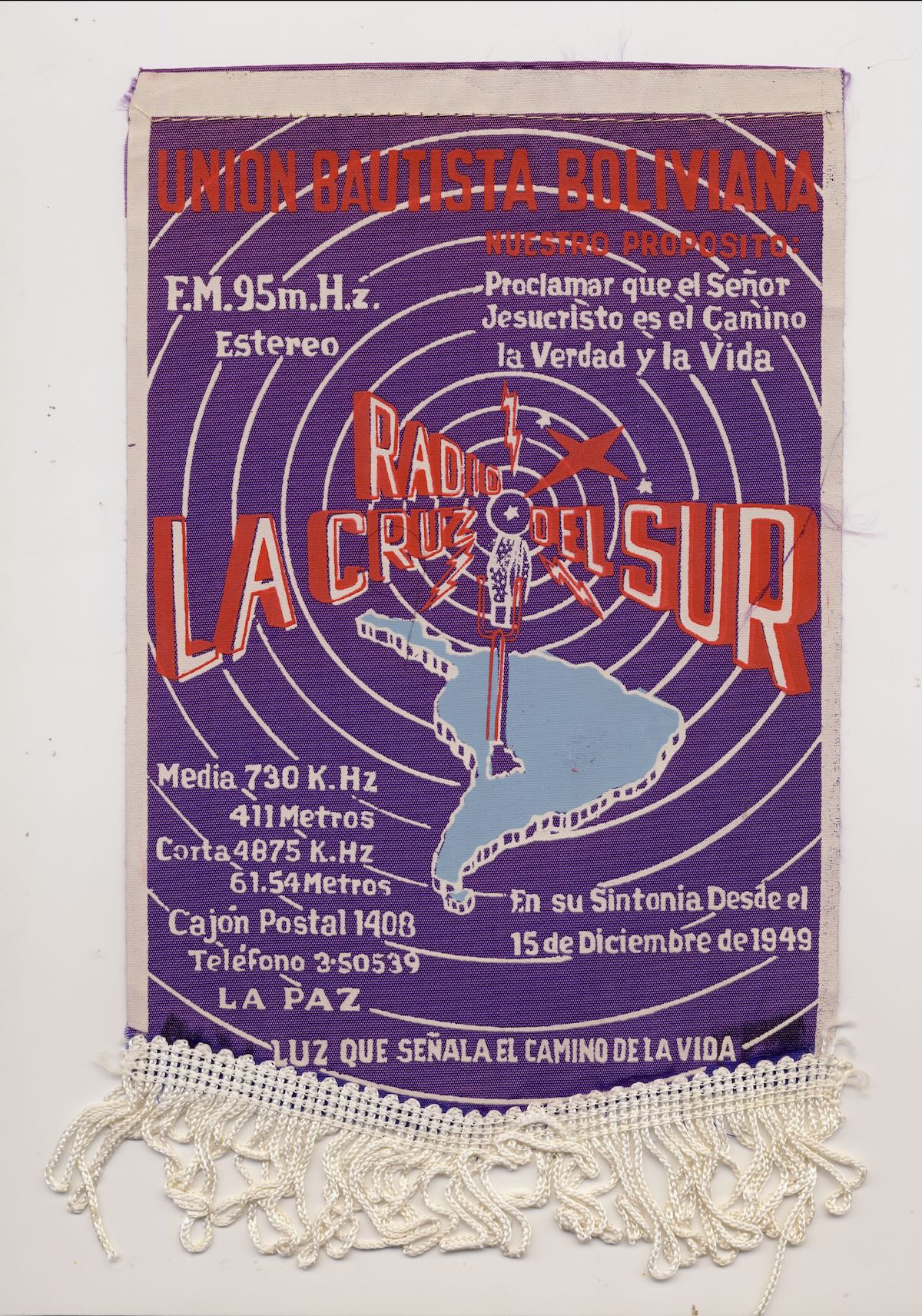

La Cruz del Sur was founded in 1949 by Canadian missionary Sydney H. Hillyer and the Canadian Baptist Mission. It broadcast on 4875 kHz shortwave for many years. My last log of it was in 2003.

La Cruz del Sur QSL from the 1980s.

La Cruz del Sur pennant from the 1980s.

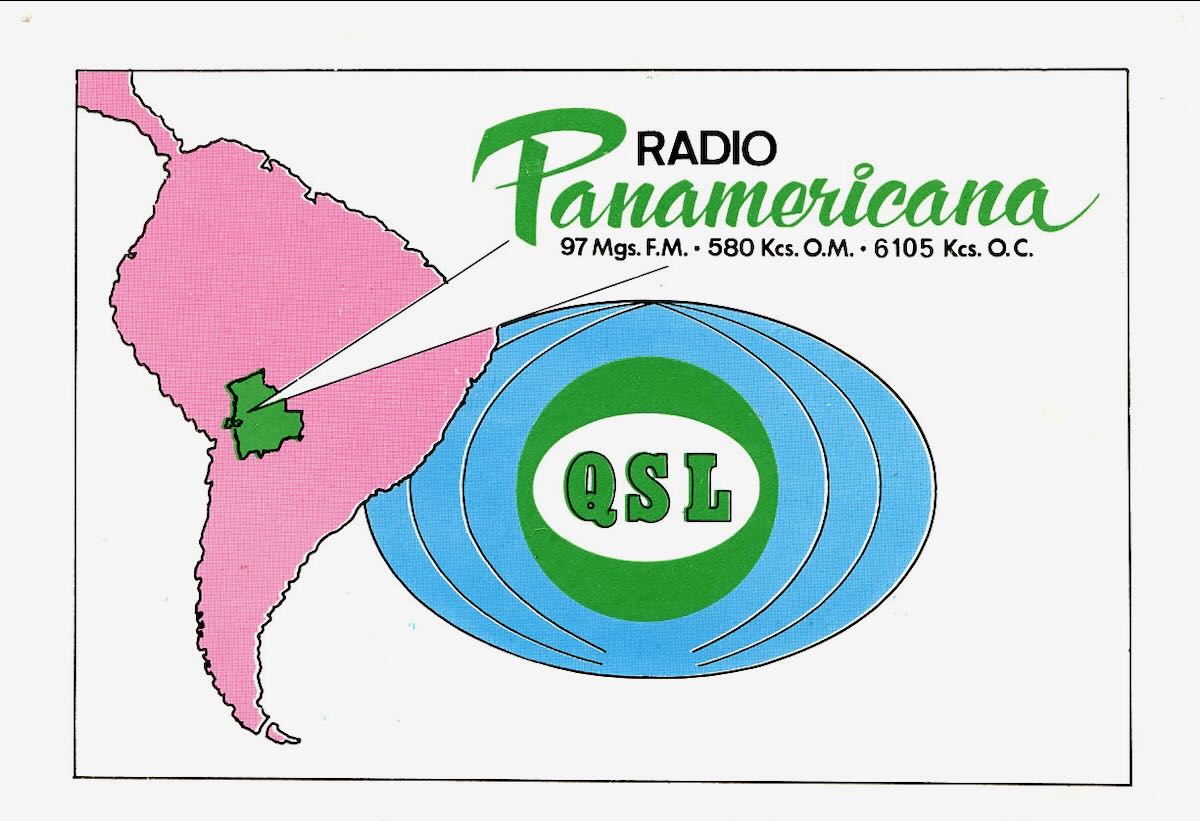

Radio Panamericana has been one of Bolivia’s most respected news stations for many years. In the 1980s it was active on 6105 kHz shortwave and was a good verifier thanks to Vice President Daniel Sánchez Rocha.

Radio Panamericana QSL card from the 1980s.

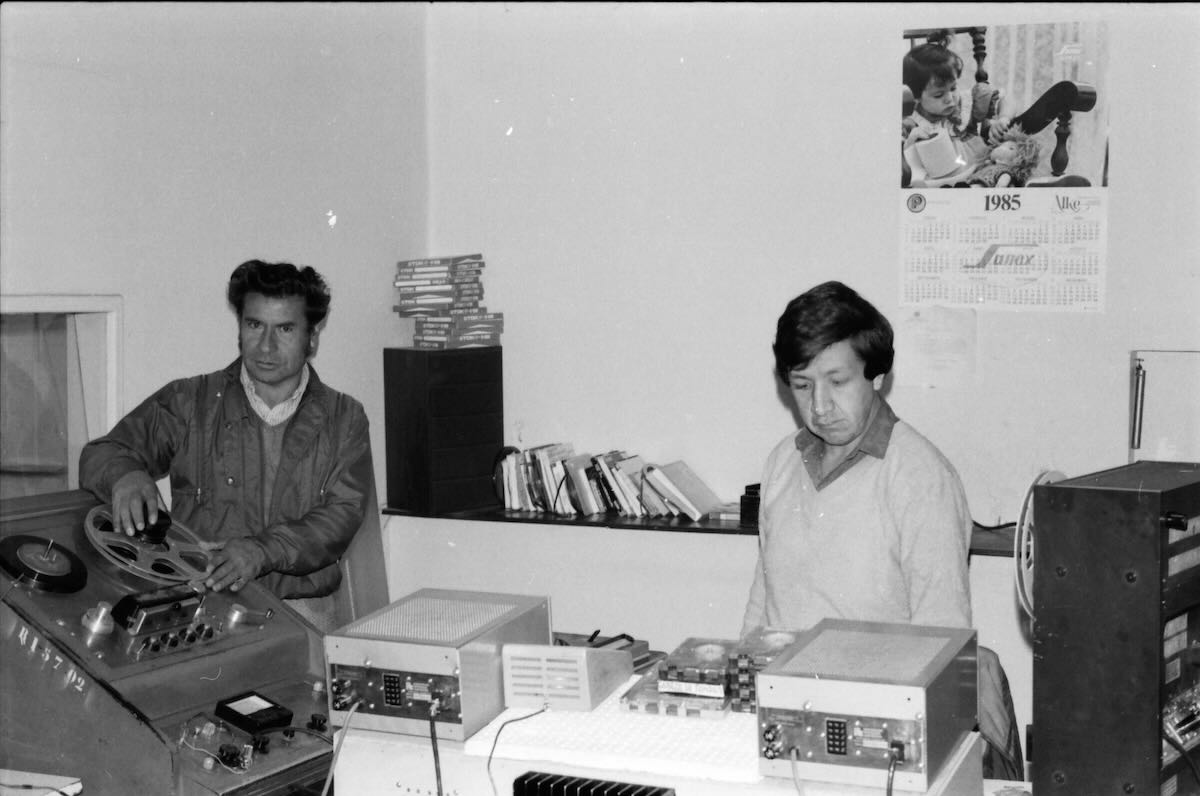

Technical staff at Radio Illimani, which used to broadcast on 6025 kHz. Named after Bolivia’s highest Andean peak, this is the national government-run radio station. In the 1980s there were several stations around the country named Radio Nacional but all were in private hands. Today Radio Illimani mostly uses the name Red Patria Nueva.

Radio Nueva America in La Paz on 4795 kHz was one of the easiest catches from Bolivia in the 1970s and 1980s. The station was founded by the late Raúl Salmón, one of Bolivia’s best-known playwriters and one-time mayor of La Paz.

Radio Nueva America decal from the 1980s.

Although not an Indian himself, Raúl Salmón put on the air what is thought to be the first regular radio program in the Aymara language while working as program director at Radio Altiplano in the 1950s. That may sound unimportant, but over 70% of Bolivia’s population are indigenous people, mostly Aymara-speakers in the Andean highlands. The native people and their culture were considered inferior and so no one had thought them worthy of a radio program before. From the time of the Spanish conquest until the mid-twentieth century the Indians were little better than slaves as they worked the fields and, especially, the rich silver and tin mines. They produced the country’s wealth but it all flowed to a small wealthy elite.

A 1952 revolution led to free elections that brought progressives to power for the first time. Twelve years later a military coup put an end to the era but not before major economic and social changes had been made. One of the most far-reaching changes was the legalization of trade unions. Bolivia’s work force quickly organized and, after centuries of mistreatment, the unions were not afraid of confronting the power structures that had repressed them. Mining was the foundation of Bolivia’s economy so the miners’ unions became an important political force. Because Bolivia had a high rate of illiteracy union leaders saw radio as a key to uniting their members and improving their lives. Local miners’ unions around the country began operating illegal radio stations. Most eventually became legal and at the peak there were around three dozen miners’ stations. Other trade unions followed the example of the miners and established their own broadcasting stations.

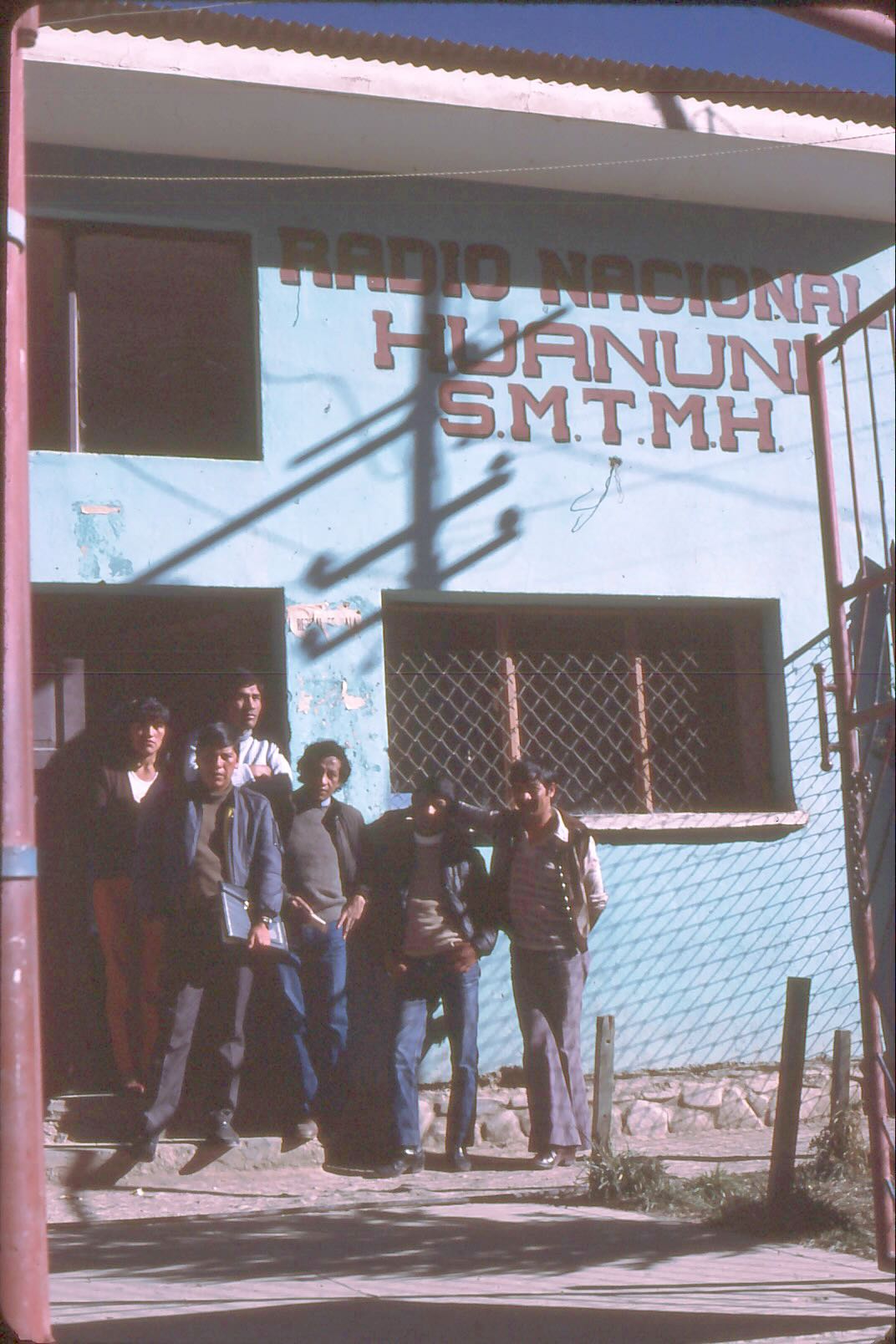

One of the most famous of the miners’ stations, Radio Nacional Huanuni broadcast on 5965 kHz shortwave for many years from the town of Huanuni, near Oruro. It still broadcasts on FM. The station was recently featured in a documentary about community radio on the BBC.

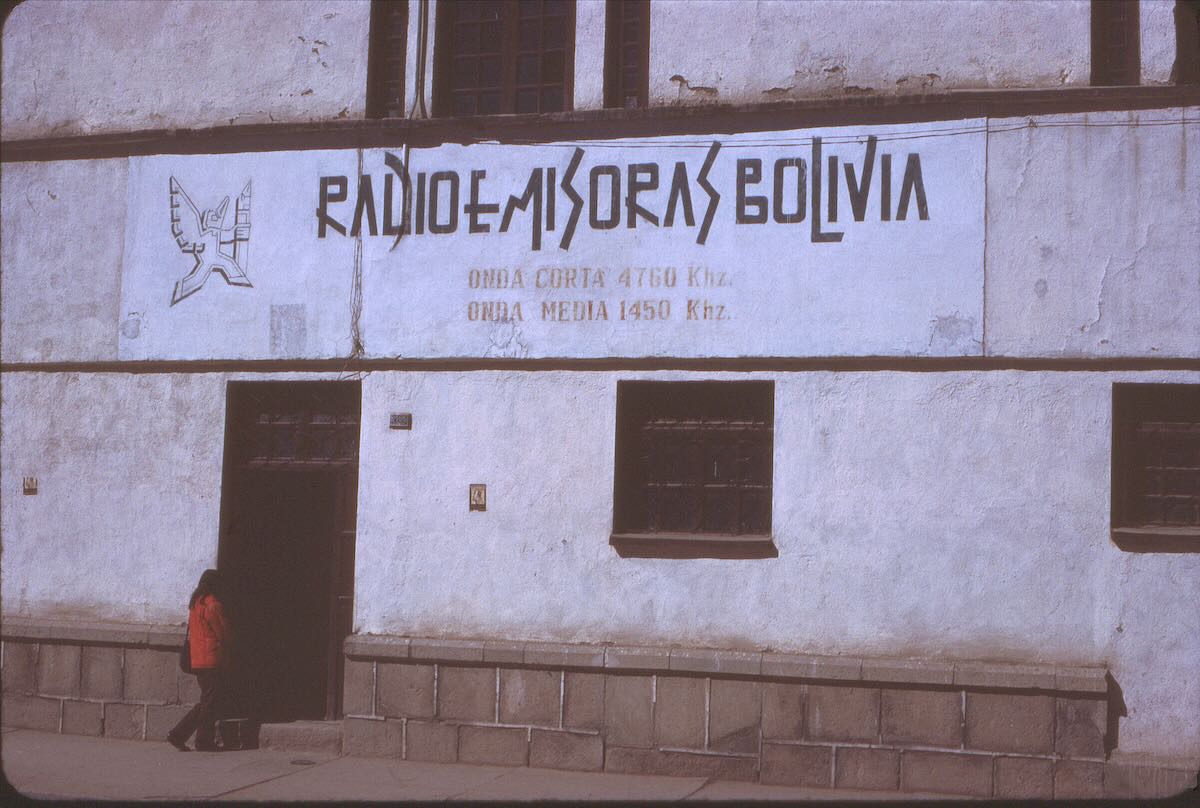

Broadcasting from Oruro, Radioemisoras Bolivia on 4755 kHz (not 4760) was a tough catch for North American DXers in the 1970s and early 1980s. It was operated by the union of campesinos (peasant farmers).

Also broadcasting from Oruro, Radio El Condor was run by the railroad workers’ union. Its frequency of 6069 kHz was rarely heard in North America.

Like all Latin American countries, Bolivia has a long history of broadcasting by the Roman Catholic Church. In the 1950s the Church in Bolivia sided with traditional power structures and saw the trade unions as gateways to Communism. That changed in the 1960s as the church began to see promoting social justice as the best way to prevent Communism. The real turning point came in 1967 when military forces massacred hundreds of striking miners and their families at the Siglo Viente mines. From that point on most Catholic radio stations in Bolivia became close allies with the working people, the trade unions, and their radio stations.

The right-wing dictatorship of General Hugo Banzer from 1971 to 1978 brought all reforms to a halt. Banzer suspended the trade unions and most political parties and sent thousands into exile. Hundreds of political opponents were arrested, tortured, and executed. Some of the miners’ radio stations were allowed to continue broadcasting but only under close supervision by the military. The Banzer government also did what it could to stifle dissent in the Catholic Church but had to tread more carefully there. As a result, Catholic radio stations became the most trusted news sources in Bolivia in the 1970s.

Foremost among those broadcasters was Radio Fides in La Paz, which in the late 1970s was an easy catch for DXers on 4845, 6155, and 9625 kHz. One of the station’s newsmen, Eduardo Pérez, became especially well-known for his work in turning Radio Fides into one of the most trusted voices in Bolivia. Banzer’s fall in 1978 brought some return to freedom but not stability. Bolivia went through four presidents in sixteen months before a new Congress made Lidia Gueiler interim president. Bolivia’s first woman leader, she guided the country through elections and prepared to turn power over to her successor.

My 1979 QSL from Radio Fides was signed by Eduardo Perez. Perhaps other DXers also have QSLs signed by him.

But not everyone wanted to see democracy come to Bolivia. On July 17, 1980, General Luis García Meza launched one of the most violent coups in South American history. García Meza had been one of Banzer’s associates but this was not just another military coup. The plotters included Bolivia’s most notorious cocaine lords and Klaus Barbie, a former Nazi Gestapo officer known as ‘The Butcher of Lyon’. A united force of regular army units, drug-lord paramilitary forces, and mercenaries hired by Barbie quickly spread out through La Paz to search out and destroy all potential opposition. One of their targets was Radio Fides. Armed with machine-guns and backed by a tank, a force of soldiers and hired thugs stormed the undefended Catholic radio station and shot up all the equipment. They then interrogated the station staff one-by-one as to the whereabouts of Eduardo Pérez, who they probably had orders to execute. Each person told the soldiers that Pérez was out on assignment so they left the ruined station not knowing that Pérez was one of the people they had been talking to. He was later able to escape the country.

Meanwhile as coup forces occupied other towns and cities around the country it was the miners who provided the stiffest resistance. Some of the mining towns held out for up to three weeks, keeping their radio stations on the air the entire time. García and his allies did get full control of the country but the violence of the coup combined with the cocaine connection and Nazi involvement made the new government an international pariah. García was forced out of power a year later and in 1982 the government was turned over the winner of the 1980 election.

Saved from the wreckage at the station, this clock preserves the time of the exact moment that Radio Fides was attacked during the 1980 coup.

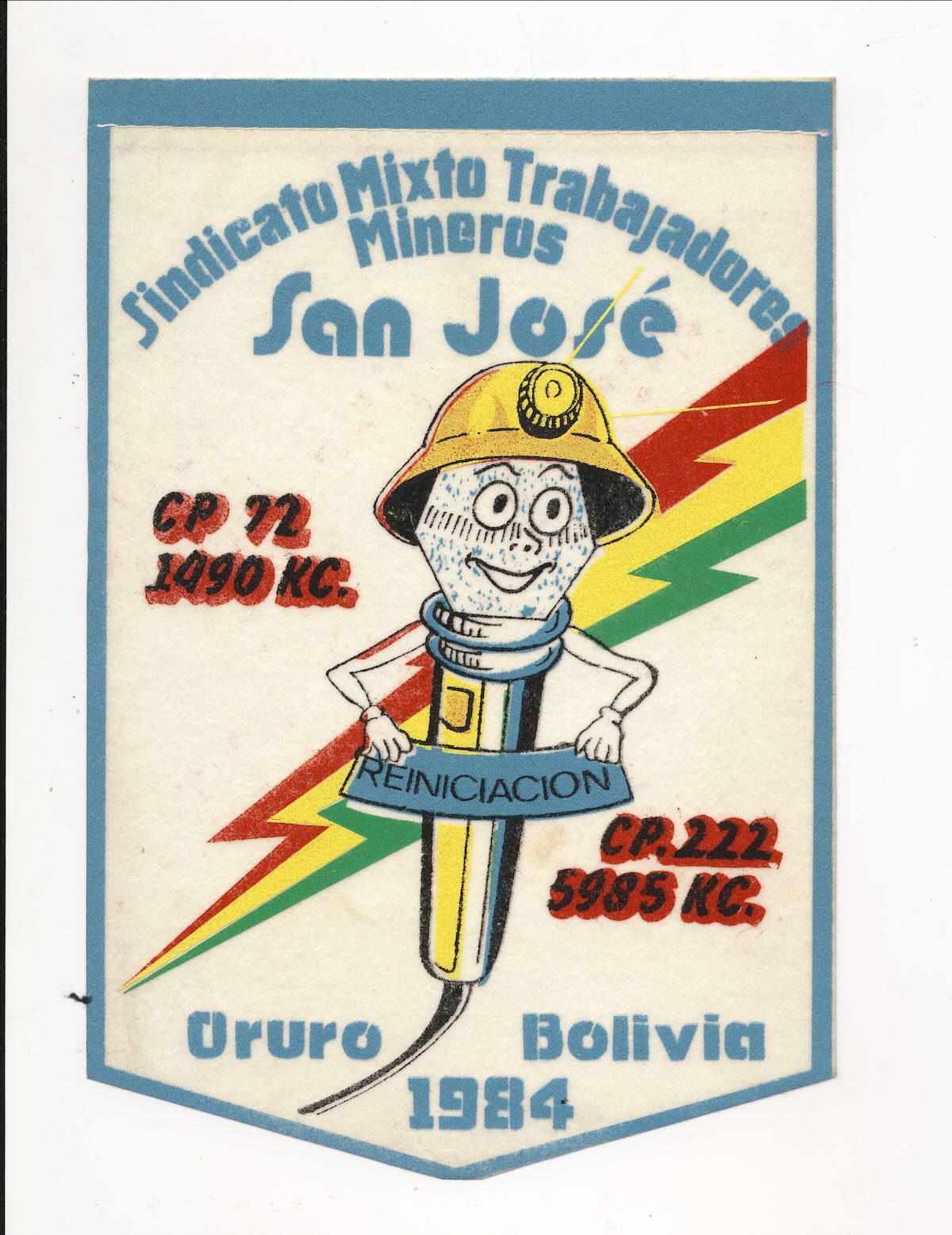

Radio San José was the voice of the miners’ union in Oruro. This pennant celebrates their return to the air (reiniciación) in 1984, after having had all their equipment destroyed during the 1980 coup. When I visited them in 1985 they were broadcasting from a few small rooms behind a community auditorium.

A privately-owned commercial station, Radio Nacional de Cochabamba broadcast on 5975 kHz in the early 1980s.

Radio Nacional de Cochabamba carried a DX program by the Bolivia DX Club, which was headquartered in Cochabamba.

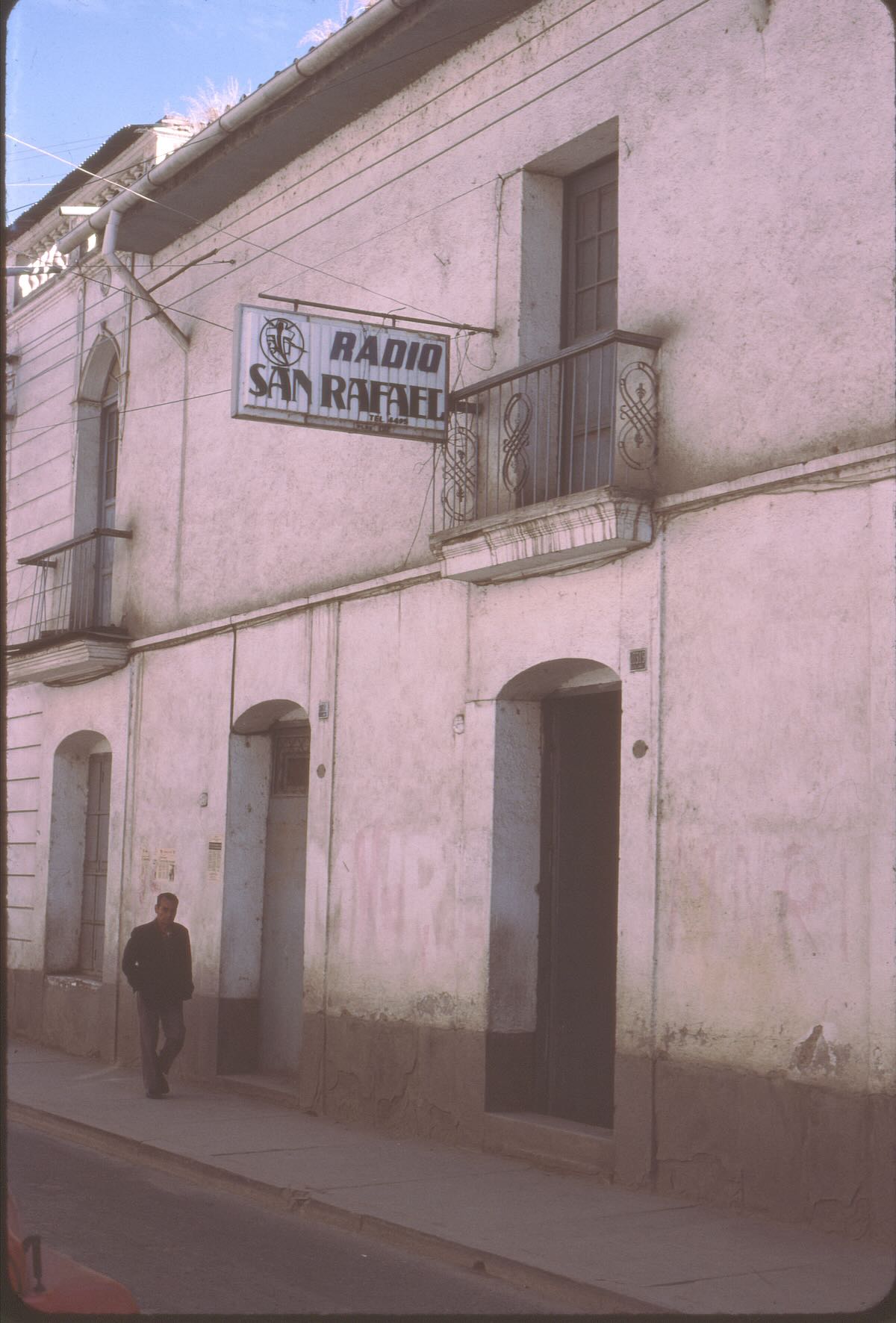

Radio San Rafael was a Catholic broadcaster from Cochabamba that used 5055 kHz in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Radio Batallon Topater in Oruro was one of several military-owned broadcasters set up during the Hugo Banzer dictatorship. The stations were staffed by civilians and mostly functioned as regular commercial broadcasters. Here I am with the station manager and secretary during my 1985 visit.

Tenth anniversary pennant for Radio Batallon Topater.

Display wall of samples at a pennant printer in La Paz. The pennants are mostly for schools, civic organizations, and futbol teams except for one from Radio Altiplano. I offered the shop owner twenty dollars for that one but he refused to sell.

After 1985 Bolivia’s mining economy went through may tough years and during that time many mines shut down. Bolivia’s politics have continued to be turbulent but the country has now gone over four decades without either a military coup or a dictatorship. Bolivia is still one of the poorest countries in the hemisphere but the Aymaras and other indigenous people now fully exercise their rights as citizens. In 2006 Evo Morales, an Aymara, was elected as Bolivia’s first indigenous president. Morales had started his career as leader of a local farmers’ union and, unsurprisingly, governed from the left. His critics denounced him as a radical but Bolivia’s economy grew more under his presidency than at any other period in its history and poverty was reduced by over 25%. Having broad popular support, he had little trouble getting presidential term limits ended so he could be reelected two times. But Morales’ sometimes heavy-handed tactics and flamboyant character caused even his strongest supporters to nickname him ‘Ego’ Morales. Morales was forced to resign in 2019 after unsuccessfully attempting to run for a fourth term in office.

As mines closed in the 1980s and 1990s, so did the associated local unions and their radio stations. Only a few such as Radio Nacional de Huanuni have survived and none have been on shortwave for years. The only Bolivian broadcaster with a connection to the miners and still on shortwave is the Catholic Radio Pio Doce on 5952 from the mining town of Siglo Viente.

For DXers, miners’ radio on shortwave from Bolivia is gone and won’t return. But don’t grieve for the miners. The new silver and gold of the mining industry is lithium and Bolivia has the world’s largest deposits.

Hi,

I just found this interesting site, regarding radio stations from Bolivia.

I run world’s one and only museum for radio pennants. It’s a private and non-commercial collection.

I own more than 220 different pennants from Bolivian radio stations. I’d be interested in exchanging photos

or even pennants.

Several years ago I also travelled Bolivia, visiting many stations.

Hoping to read you soon.

Regards from Bavaria / Germany

Andy

Top stuff, Don! Your article brought back memories of great Bolivian stations. Interesting photos, too. Many thanks.

Thank you for the good views (and memories). It’s amazing now how many stations now stream from that country, well over 500.

Back in the late 70’s La Cruz del Sur ran a 30-minute Sunday-night English lanuage playout of Billy Graham. That’s how non-Spanish speakers could DX the station.

If you listen to today’s IDs for Radio Panamericana , especially the intro for “El Panamericano” news block you will hear the same IDs as in the late 1970s. They still even run a classical music block after the afternoon news so listeners can rest (and digest their big Bolivian lunchtime meal). Another finding- the stream of Radio Nacional Huanuni carries their same shortwave ID as heard in the 1970s.

Back in the day, many local outlets relayed the both Panamericano and La Cruz del Sur’s news product via shortwave. The “honorifics” for Radio El Chaco in Yacuiba could be heard every weekday night as they would relay BBC’s Spanish service newscast. Today, satellite-fed FM repeaters provide national relays for most of the La Paz stations so no need for shortwave.

If you want to follow events in Bolivia and speak Spanish, Radio Panamericana remains the “gold standard.” I also follow Erbol, Radio Fides, Radio Centro (Cochabamba), Radio el Deber (Santa Cruz). Radio Global (Tarija), Radio La Plata (Sucre) among others.

Oh yes, Radio La Plata (Sucre) was cool in that they had a 31 meter outlet, perhaps just running it just five hours during midday. It’s real use was for Sunday football (soccer) broadcasts into the late afternoon.

How times have changed…

I can only concur with the thoughts of TomL & Jon above. Don’s story of broadcasting in the political turmoil of the time is one that needs wider appreciation.

Beautiful historical photographs and interesting stories. It certainly is worth documenting and preserving in some way, like the book idea or something similar. I like that the station kept the clock with the bullet hole, gives a tangible feeling to its history. Thanks for sharing!

Very interesting article – great blend of broadcasting history with political/historical context. It would be wonderful if Don were to write a book on the history of shortwave broadcasting in Latin America. He seems to have a depth of knowledge on the subject and years of field research.