Don’s traveling DX stories can be found in his book Tales of a Vagabond DXer [SWLing Post affiliate link]. If you’ve already read his book and enjoyed it, do Don a favor and leave a review on Amazon.

About two weeks ago I reported a mystery station identifying as the Duyen Hai Vietnam Information Station broadcasting in Thai on 8101 kHz. There is now enough information to identify who is behind the station and where it is coming from.

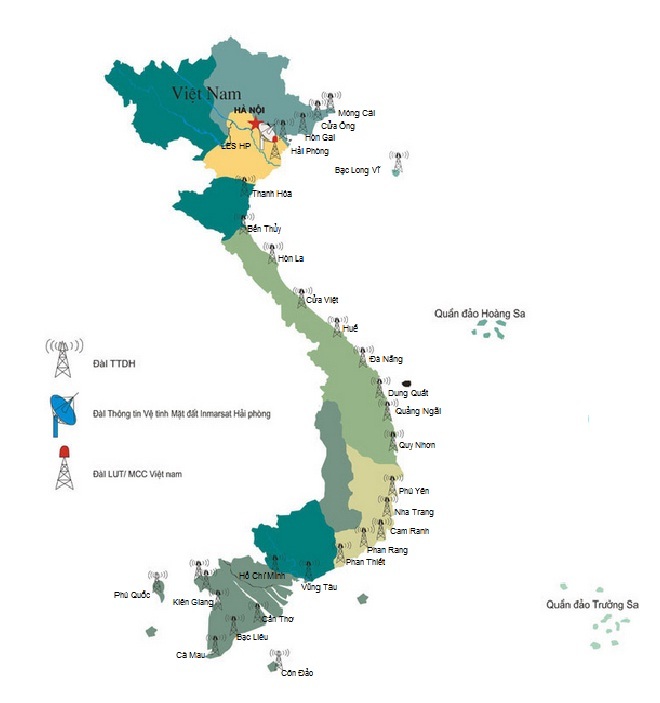

First, thanks to California DXer Ron Howard for his Internet sleuthing. Ron found a PDF file that specifically lists 8101 kHz as being used by the Hai Phong station in the Vishipel network, the Vietnam Maritime Communications and Electronics Company. This is a government-owned company that provides various services to the maritime industry. One of those services (and the one we’re interested in) is a network of thirty marine radio stations strung along the Vietnamese coast from north to south. The stations provide two-way marine radio communication and twice-daily scheduled weather broadcasts. All the stations use VHF and seventeen also use HF.

Vishipel’s weather broadcasts are listed on the DX Info Centre website and I had been monitoring those in my travels here in Southeast Asia. I suspected Vishipel was connected to this station but Ron found definitive proof that they use 8101 kHz and that the frequency comes from their station in Hai Phong. He also found this map showing all the coastal stations in the Vishipel network.

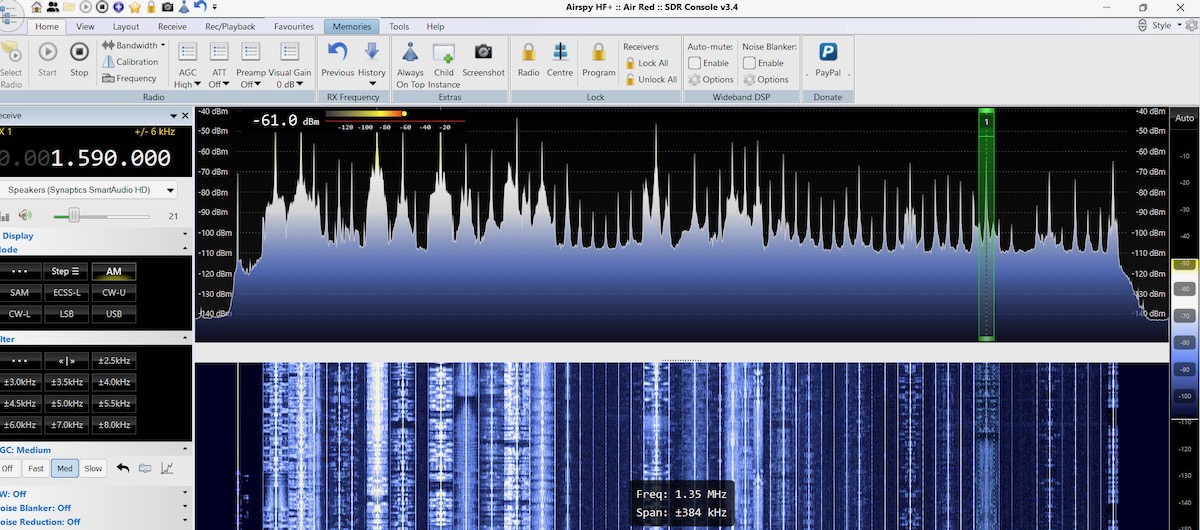

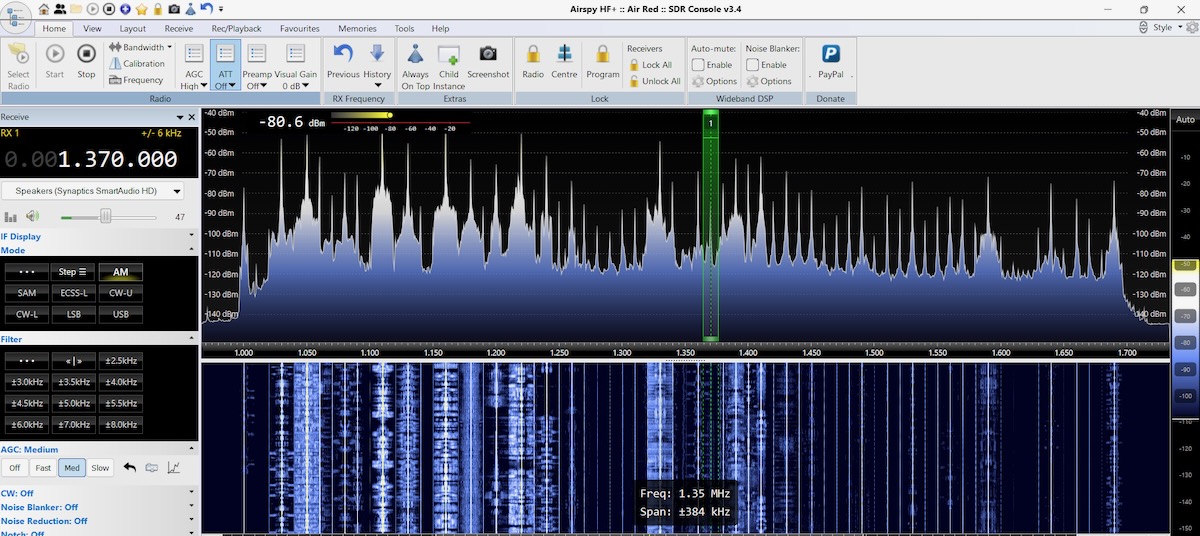

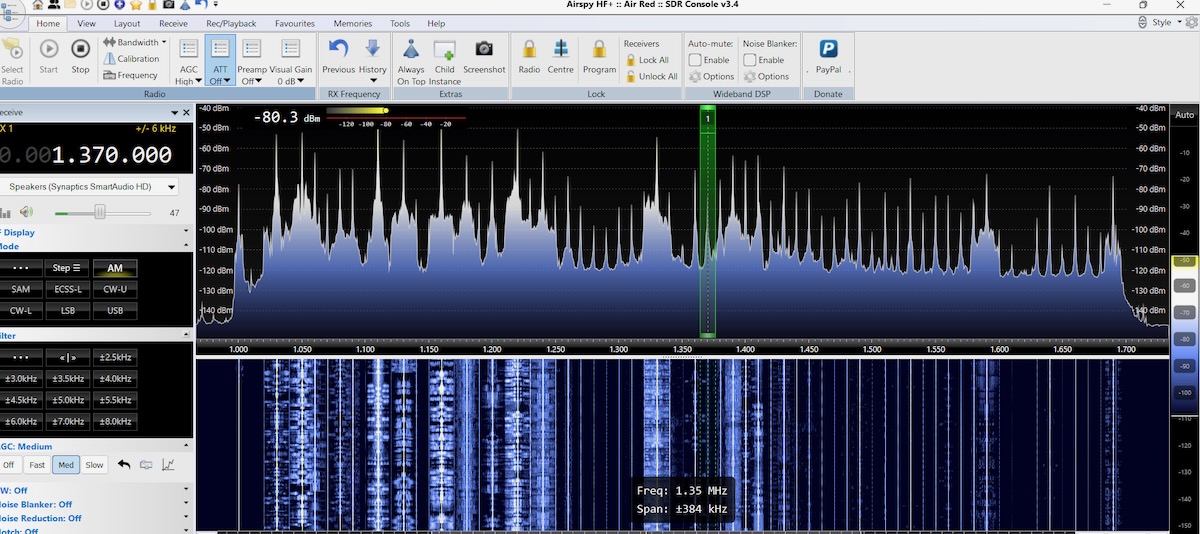

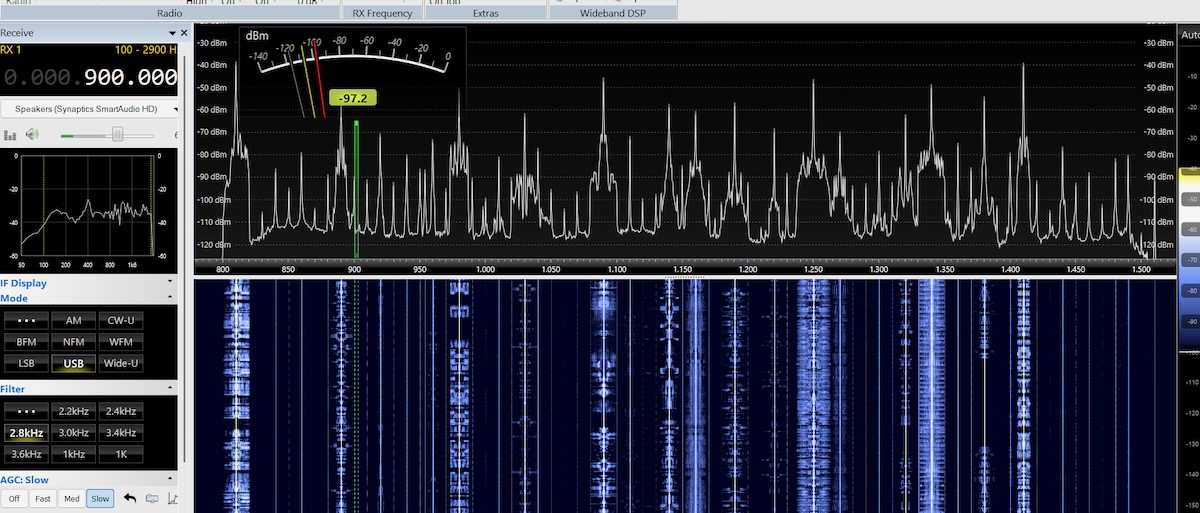

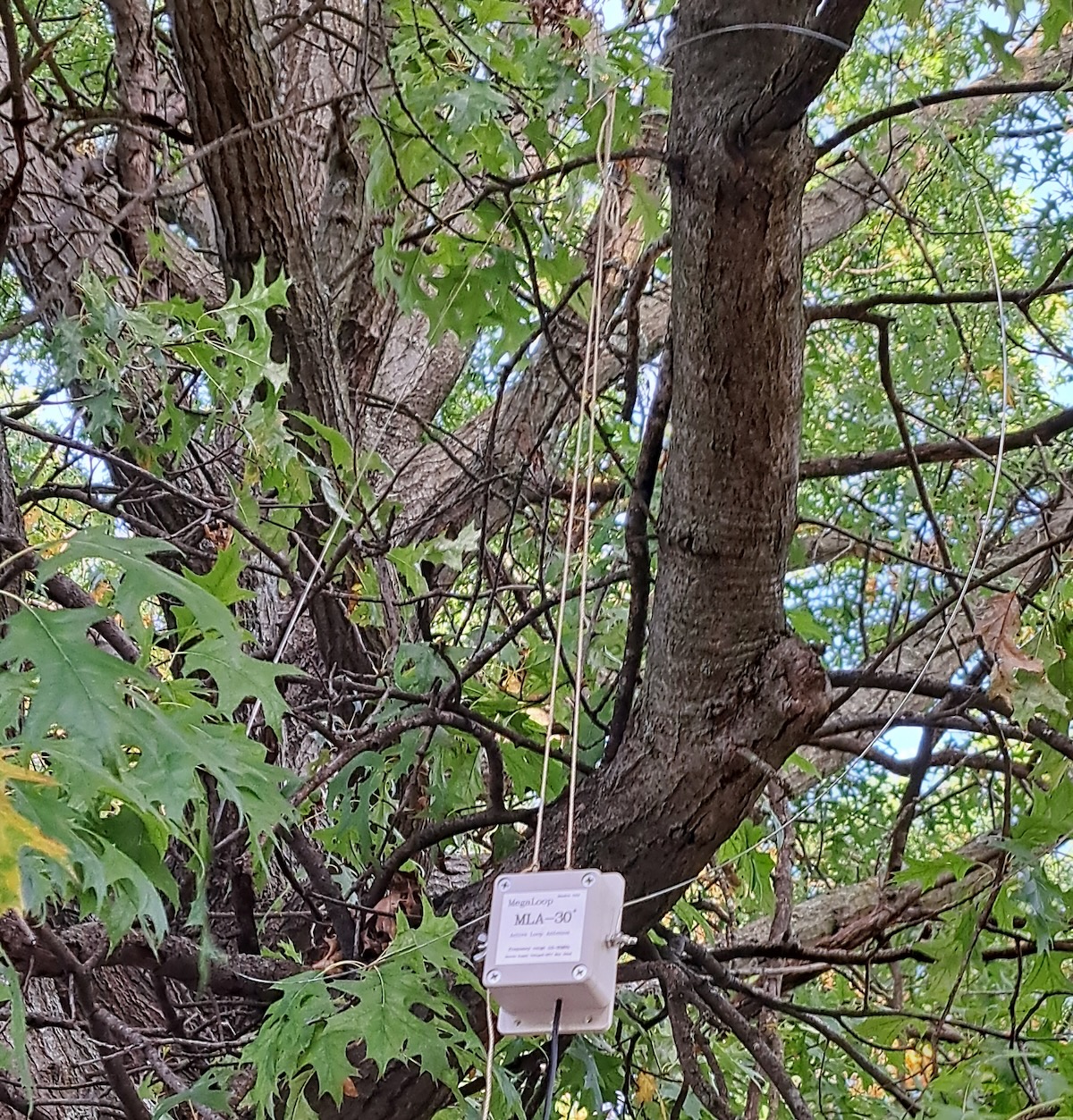

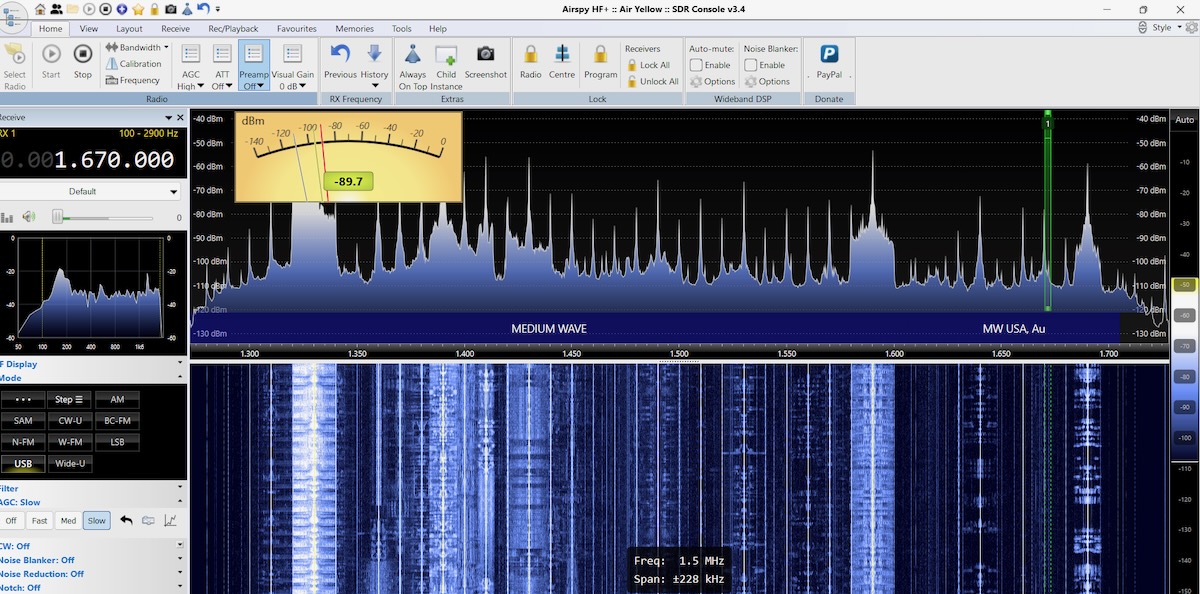

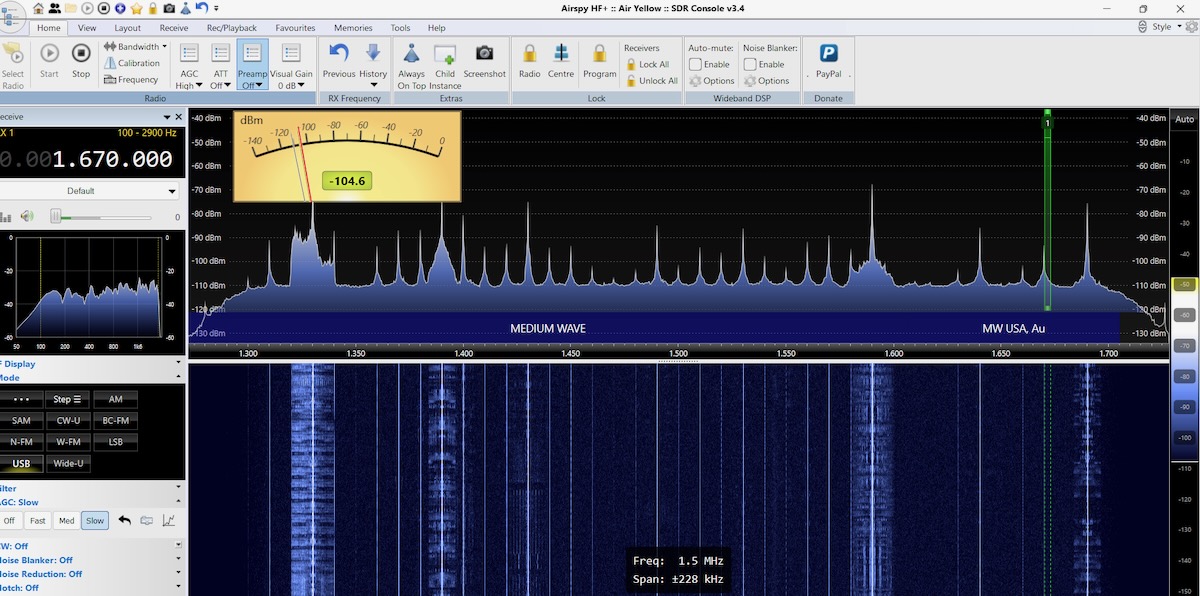

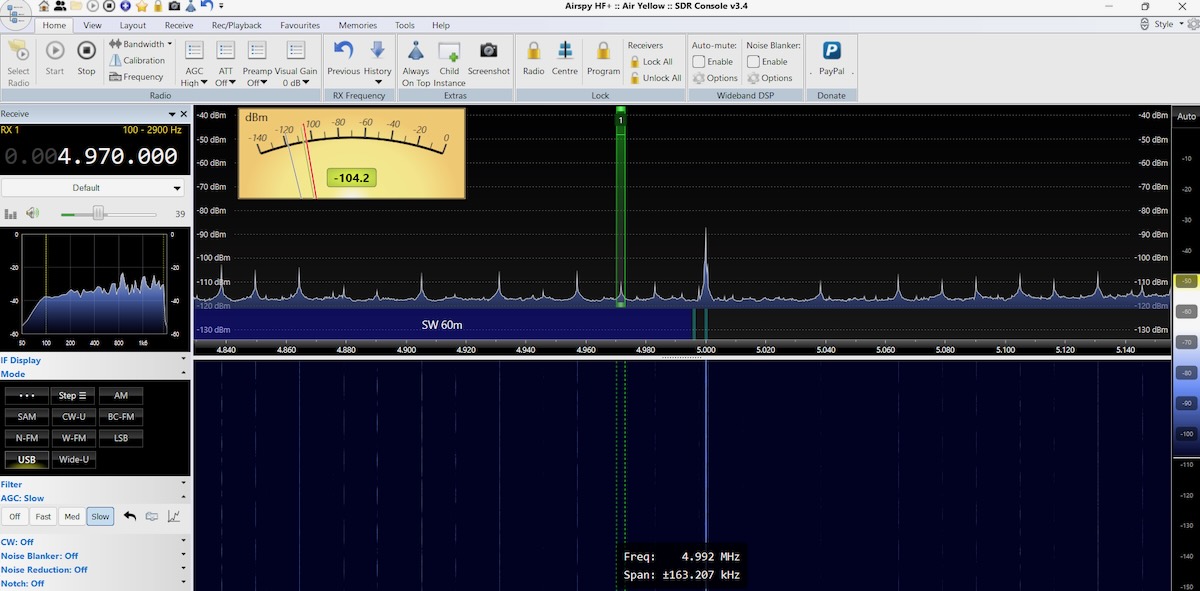

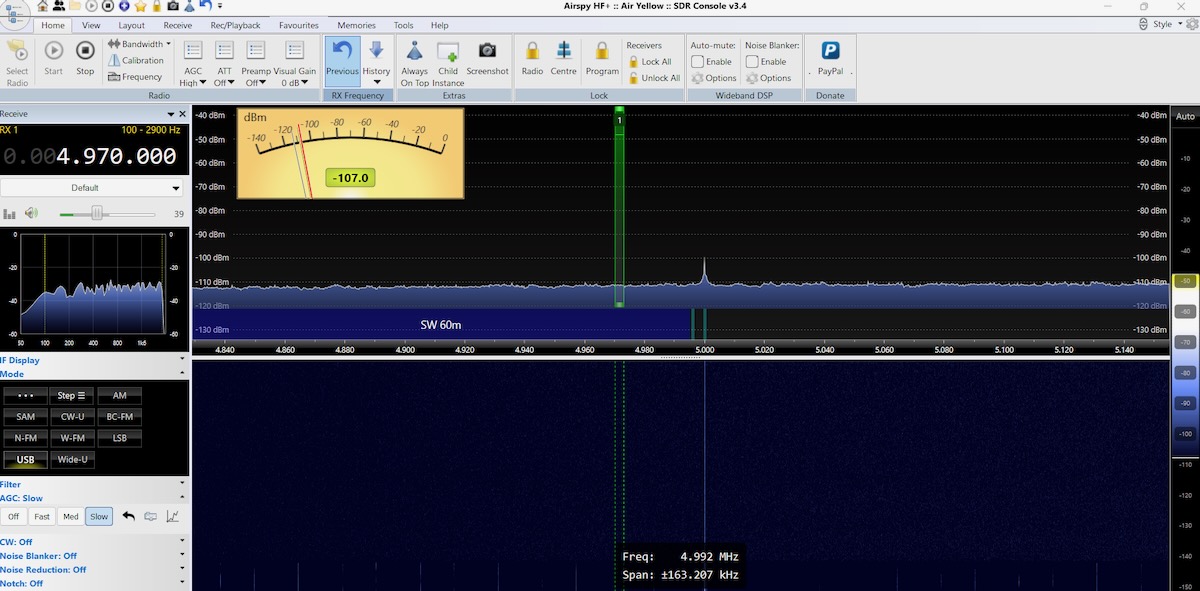

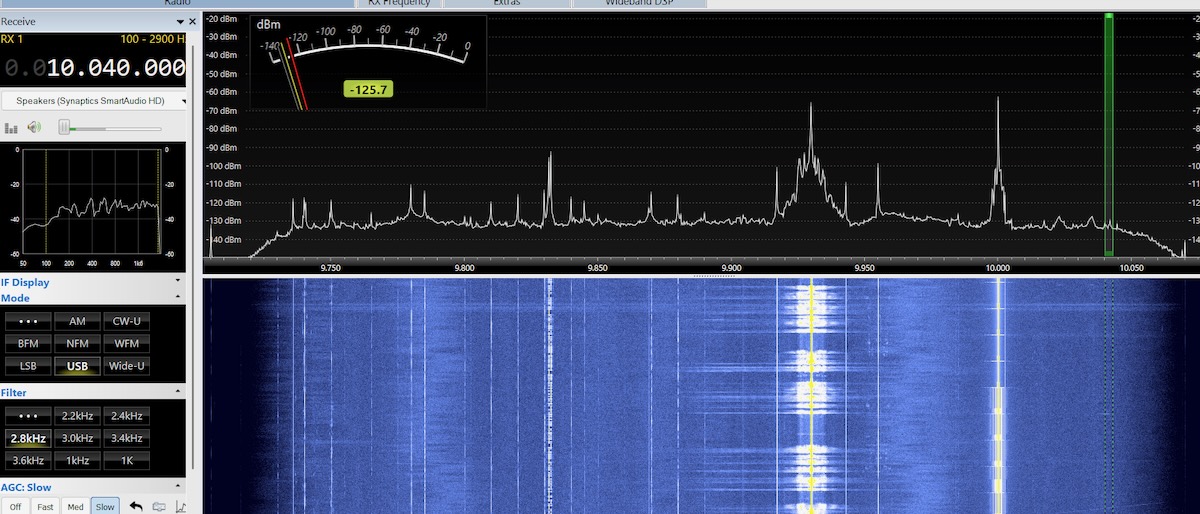

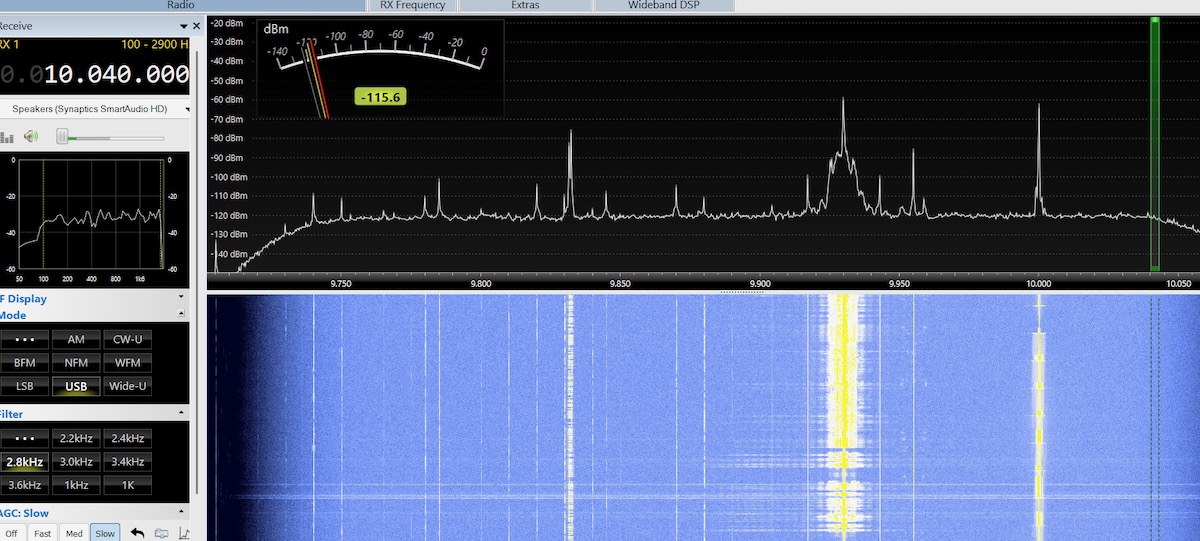

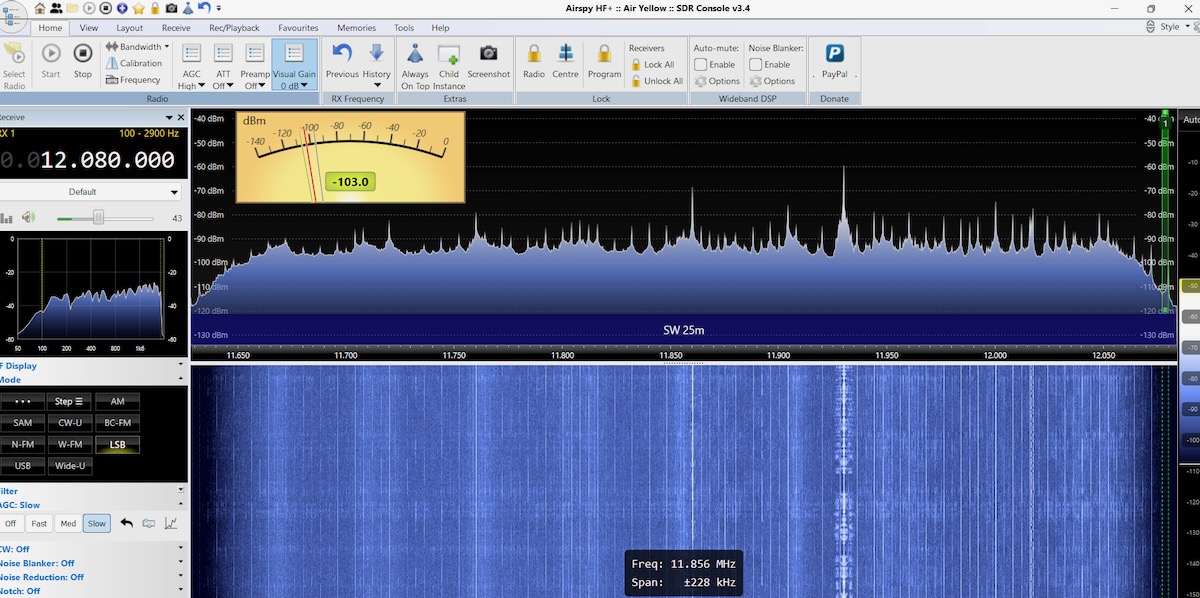

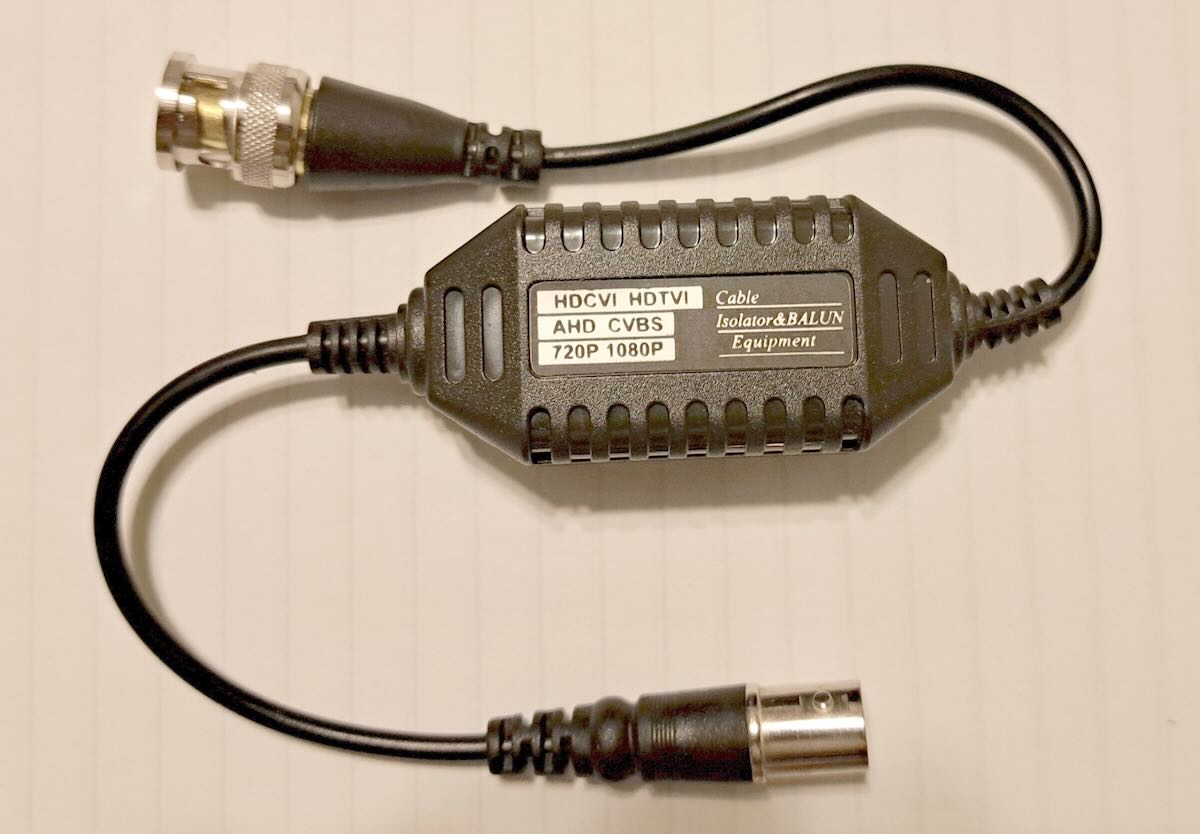

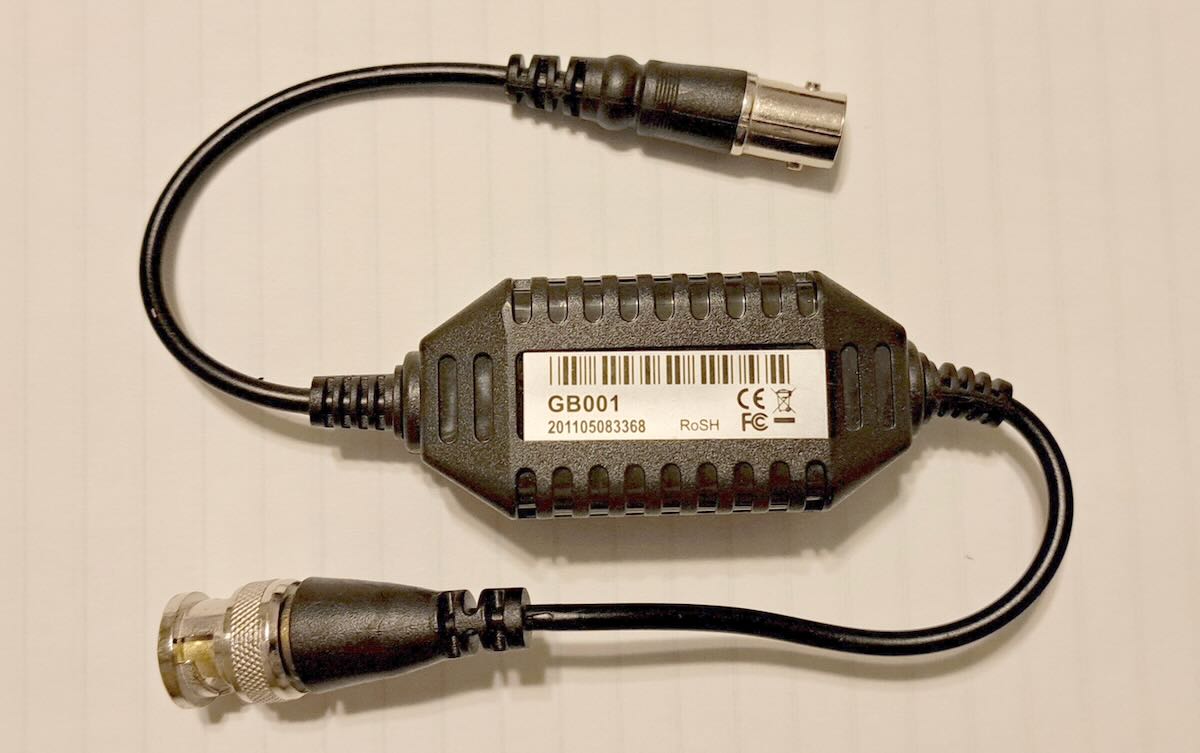

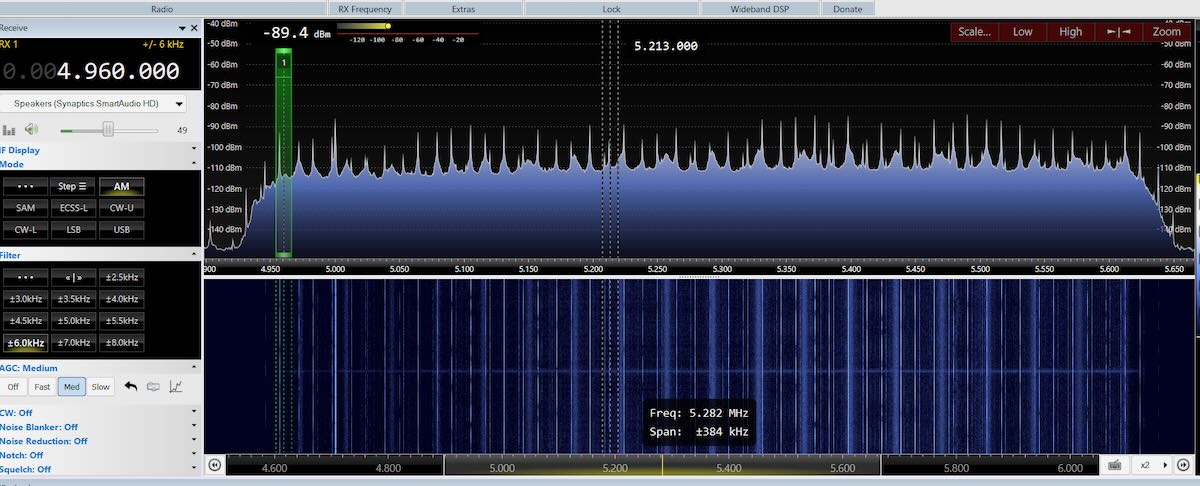

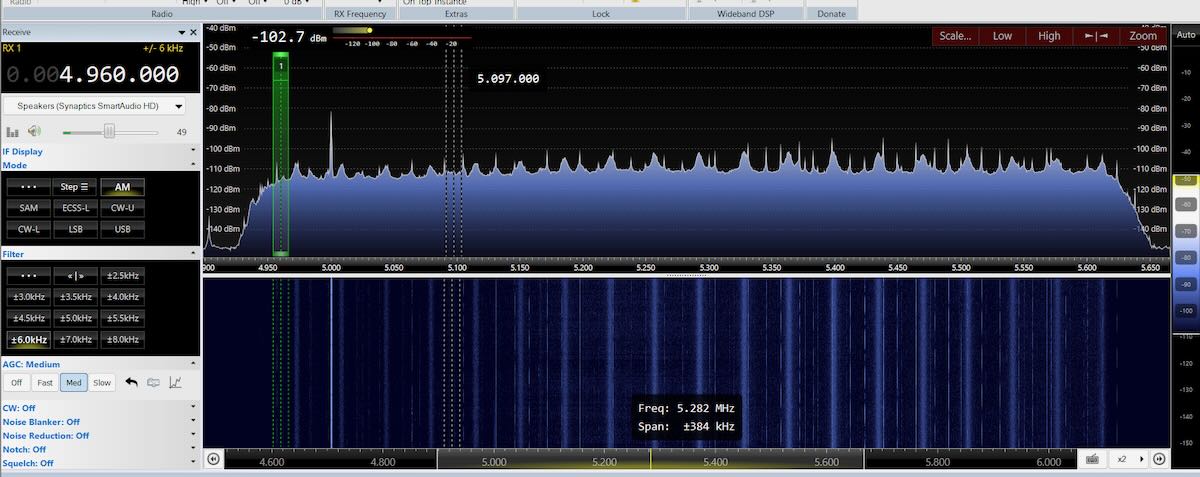

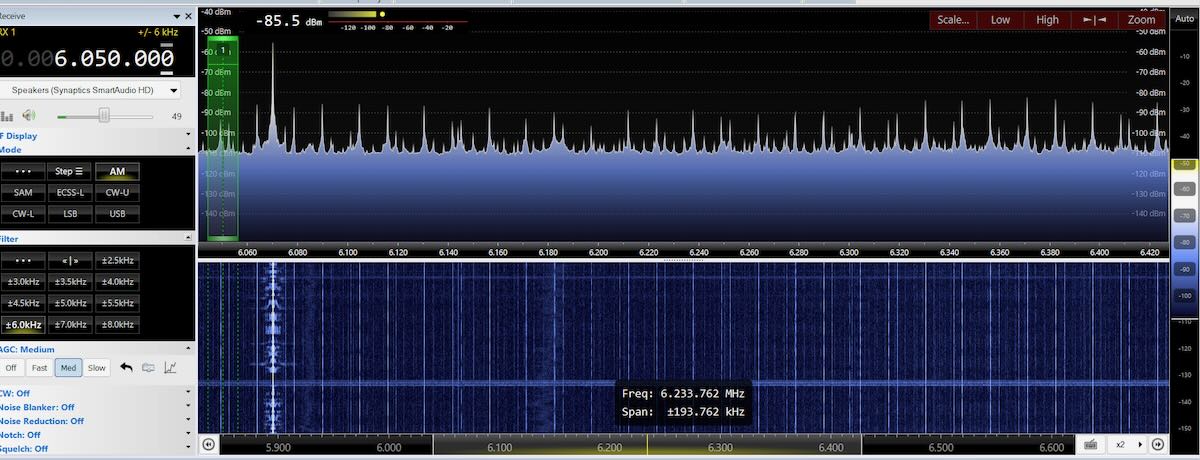

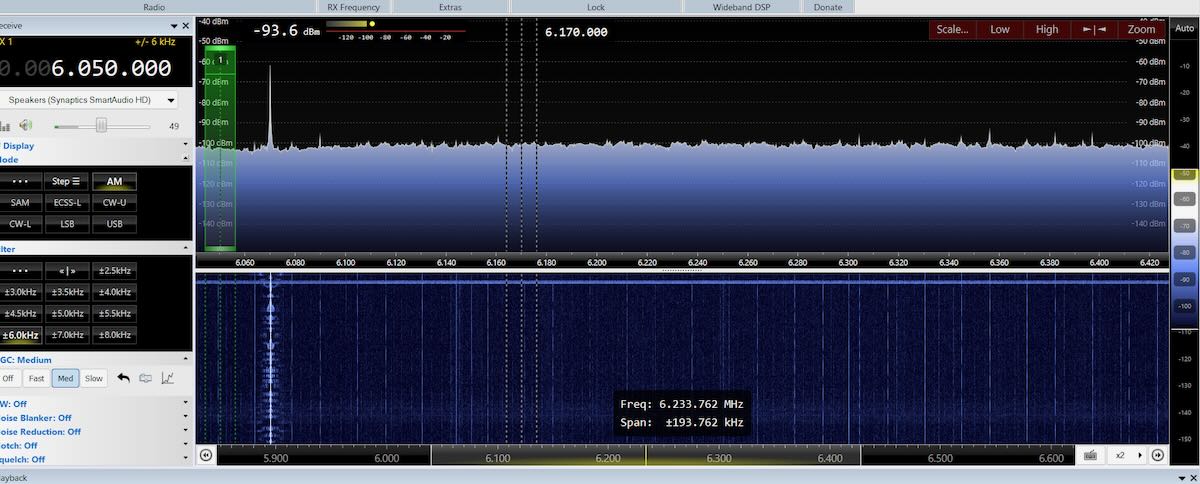

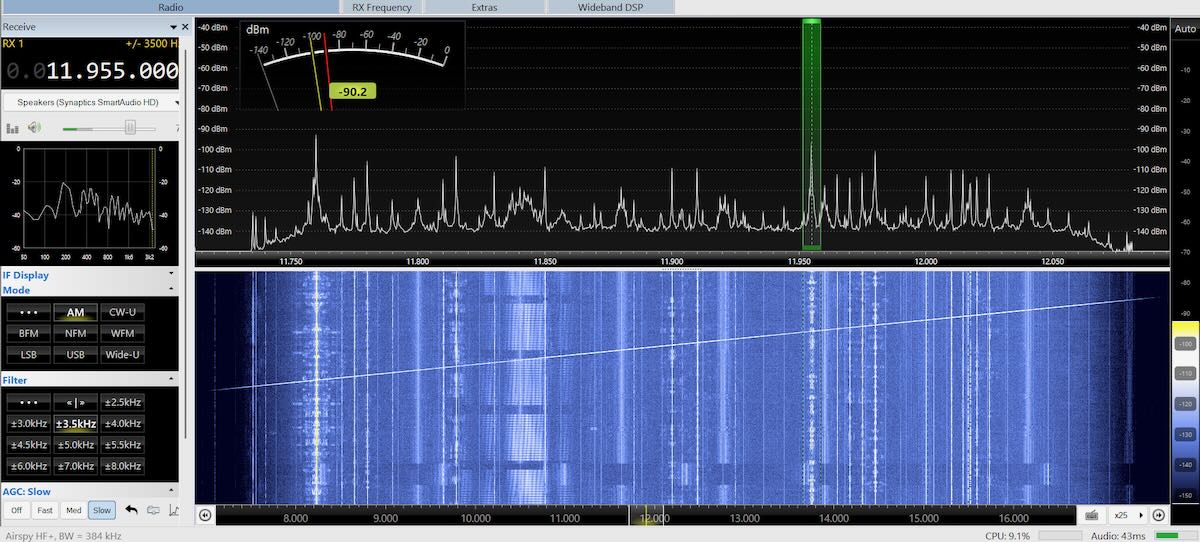

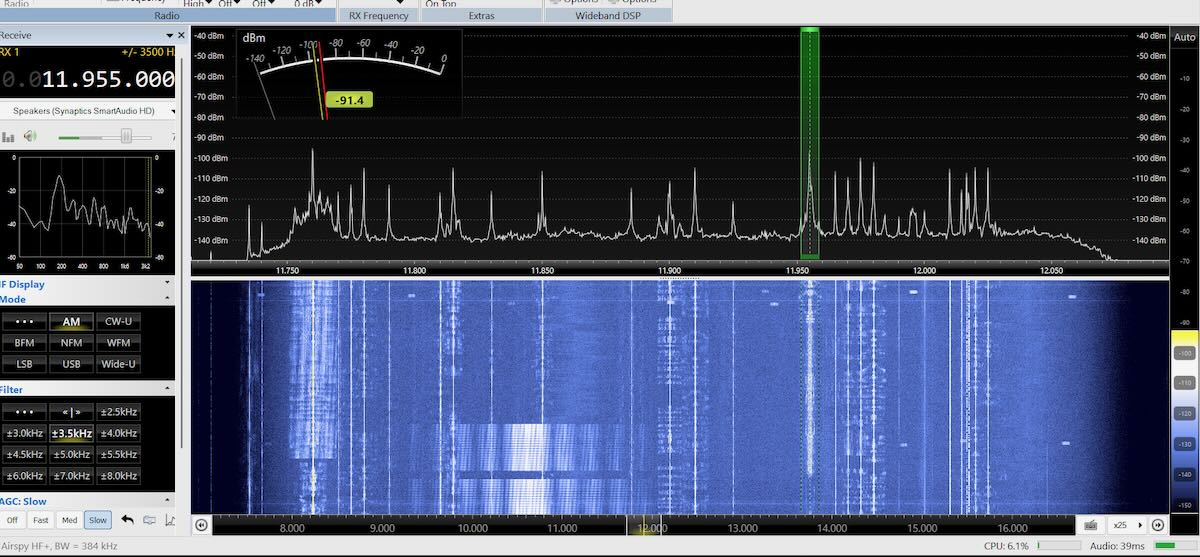

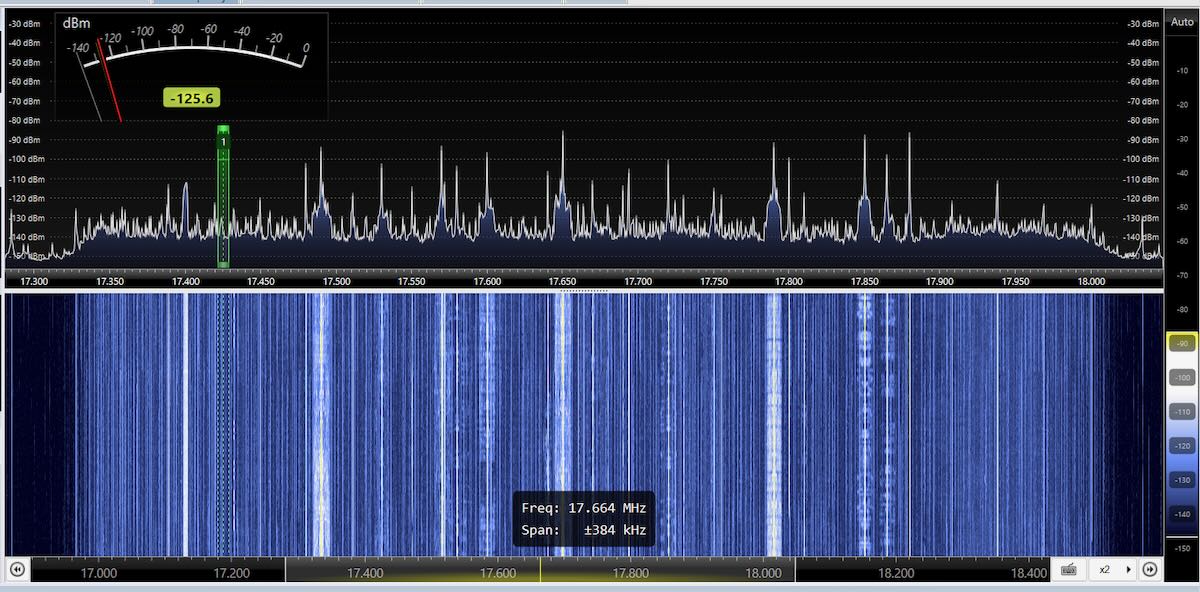

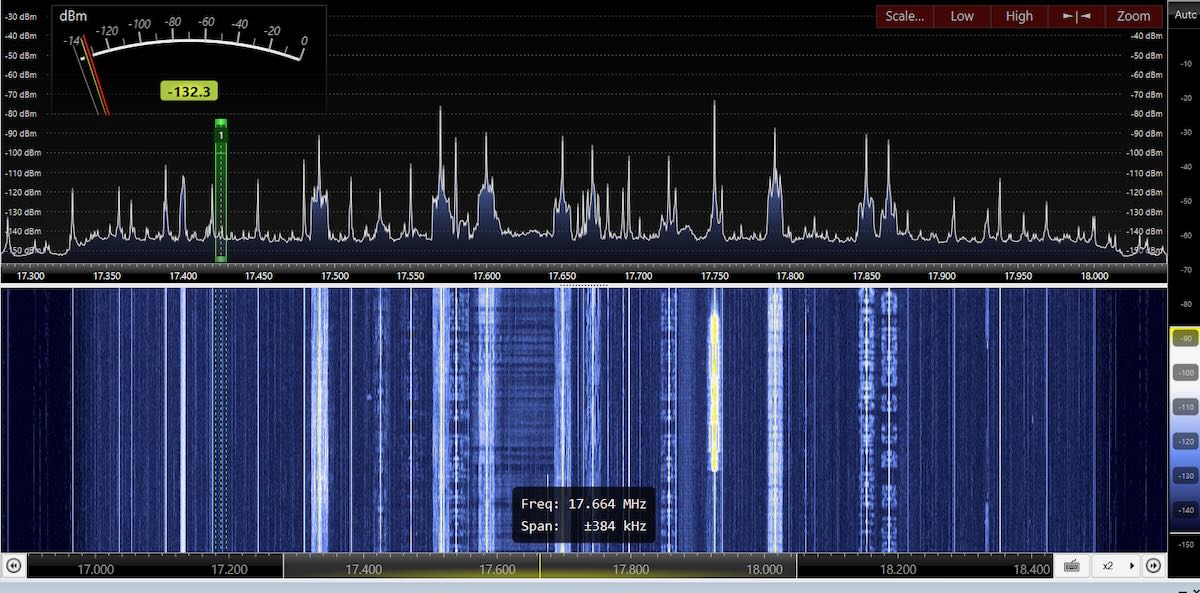

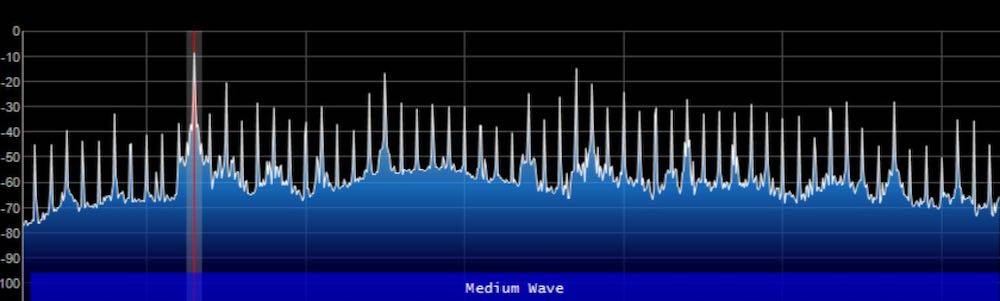

I’ve been wanting to record the station again, but my current location is not suitable for DXing. Since December 15th, I’ve been staying in the old city in Chiang Mai in northern Thailand. But a few days ago, I made a two-day DXpedition to a rural location outside the city and made a terabyte of spectrum recordings with my three Airspy HF+ Discovery SDR receivers.

It will take me a while to go through all that DX, but I’ve already checked for Duyen Hai. I had a very good signal from it on 8101 kHz at 1214 UTC on 08 January 2026. This broadcast was eleven minutes long, which is a few minutes shorter than the ones previously monitored. Here’s a recording of the entire broadcast.

The reception was good enough that Google Translate had no problem turning the spoken Thai into written English. The program was about new EU requirements around animal welfare. But the broadcast content wasn’t my focus. This was the first time I had good copy of the entire broadcast and I wanted to hear the ending. Here is a translation of the sign-off announcement.

Hello, ladies and gentlemen, today’s broadcast is over. Thank you for your attention, fishermen and audience. Our program is broadcast daily on the frequency 8101 kHz at 07:05, 19:05, and on the frequency 7996 kHz at 12:05. People can also contact their families and relatives via these two frequencies on all days of the week. I wish you all safe and effective sea trips. Hello, and see you again.

The wording is important for those of us who like to neatly categorize things. It proves that this is an intentional scheduled broadcast to an audience and not just a utility station unofficially relaying a broadcast. It’s the difference between whether it can be counted as a shortwave broadcast (SWBC) station or as a utility station. This ticks all the requirements to be counted as SWBC. Indeed, as a broadcast from Vietnam in Thai to a Thai audience it could even be considered as an international broadcaster!

The times in the announcement are local for Southeast Asia and correspond to 0005 and 1205 UTC on 8101 kHz and to 0505 UTC on 7996 kHz. I also found the program in my spectrum recordings coming on at 0019 UTC on 09 January. Obviously, they don’t care too much about beginning on time. Every broadcast I’ve monitored has begun ten to fifteen minutes late.

Unfortunately, I can’t check for the 0505 UTC broadcast as I didn’t make any spectrum recordings in that frequency range at that time (local noon). I’ll be sure to get some at my next opportunity. I also have questions about the 7996 kHz frequency. It isn’t listed in the Vishipel PDF, but it was listed as being used by the Nha Trang station in the 2017 Klingenfuss Utility Guide (the most recent I have).

Unless you’re in Southeast Asia, you won’t get a signal as good as the recording. But the Duyen Hai always uses the same woman announcer and the same musical interludes. Even if you just have a weak static-ridden signal, you should be able to match the music to that in the recording. So, can you catch this one at your location?

LINKS

- Schedule of HF marine voice weather broadcasts at DX Info Centre. The Vietnamese listings are found under frequencies 7906 and 8294 kHz. https://www.dxinfocentre.com/marineinfo.htm

- PDF file with full schedule for Vishipel stations. Times are local (Southeast Asia) times. Subtract seven hours to get the UTC time. This also includes the frequencies such as 8101 kHz that are normally used for two-way voice communication. https://vishipel.com.vn/pic/general/files/Bang%20Tan%20so%20TTDH.pdf

- This 35th anniversary video from 2017 shows several of the Vishipel stations. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oTSKzsA3IXE

- Four-minute English slide show on YouTube about Vishipel. It moves fast so you will need to pause to actually read the slides. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0htHphnnFgk

- Vishipel English website (loads very slowly) http://en.viship