Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Don Moore–noted author, traveler, and DXer–who shares the following post:

A Beginner’s Guide to ALE: Part One

A Beginner’s Guide to ALE: Part One

By Don Moore

Don’s traveling DX stories can be found in his book Tales of a Vagabond DXer [SWLing Post affiliate link]. If you’ve already read his book and enjoyed it, do Don a favor and leave a review on Amazon.

To me, part of the excitement of DXing has always been logging new stations. From the very beginning (over fifty years ago), I went after shortwave broadcast (SWBC), medium wave, and voice utility DX. Up until the mid-90s, I usually averaged logging one new SWBC station per week. Today, it’s hard to add more than one or two each year. There are also far fewer voice utility stations on the air today. At least medium wave is still going strong. Several years ago, my quest for logging new stations on the shortwave frequencies got me involved in DXing digital utility stations. I wrote an article here on monitoring DSC stations: https://swling.com/blog/2022/11/guest-post-monitoring-digital-selective-calling-dcs-with-yadd/).

But DSC is just one of several digital modes that I’ve been playing around with. The one that I’ve found most interesting – and the one that has yielded hundreds of new stations in numerous countries – is ALE.

Now, I am not an expert at monitoring ALE. I’m just an advanced beginner. But I think I know enough to help other beginners get started. And if you are an ALE expert reading this, I welcome your additions, corrections, and even criticisms to the comments section. I still have a lot to learn, too.

What is ALE?

Ever since the early days of radio, one of the most important uses of the shortwave spectrum has been two-way communication. It provides a means for an organization’s far-flung offices or bases to communicate without relying on external infrastructure. That remains true even today because satellites can malfunction and evil powers can cut undersea cables.

But shortwave isn’t consistent. The frequencies that work best between any two points will vary by time of day, time of year, solar conditions, and a host of other factors. In the old days, radio operators had to understand radio propagation to make an educated guess as to the best frequency to use to reach a particular distant station. Sometimes they guessed wrong, and stations would struggle to communicate or maybe not even connect. ALE, or Automatic Link Establishment, was designed to make two-way shortwave communication as simple as making a telephone call. Depending on your point of view, it has taken the guesswork out of frequency selection … or made it so easy that any dummy can be a radio operator.

In an ALE system, each station is assigned a unique identifier and the network has a set of preconfigured frequencies spaced throughout the shortwave spectrum. For example, here’s a partial list of frequencies and stations for the United States Air Force, one of the most active ALE networks.

USAF Common Frequencies: 4721, 5684, 5702, 6715, 6721, 8968, 9025, 11181, 11226, 13215, 15043, 17976, 18003, 23337, 27870 kHz

Most Active USAF Stations

- ADW Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, USA

- AED Elmendorf Air Force Base, Alaska

- CRO Croughton Air Base, United Kingdom

- GUA US Air Force Base, Guam

- HAW Hawthorn Air Force Base, Ascencion Island

- HIK Hickman Air Force Base, Hawaii

- ICZ US Air Force Base, Sigonella, Sicily, Italy

- JDG US Air Force Base, Diego Garcia Island

- JNR US Air Force Base, Salinas, Puerto Rico

- JTY US Air Force Base, Tokyo, Japan

- MCC Beale Air Force Base, California, USA

- OFF Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, USA

- PLA Lajes Field, Azores

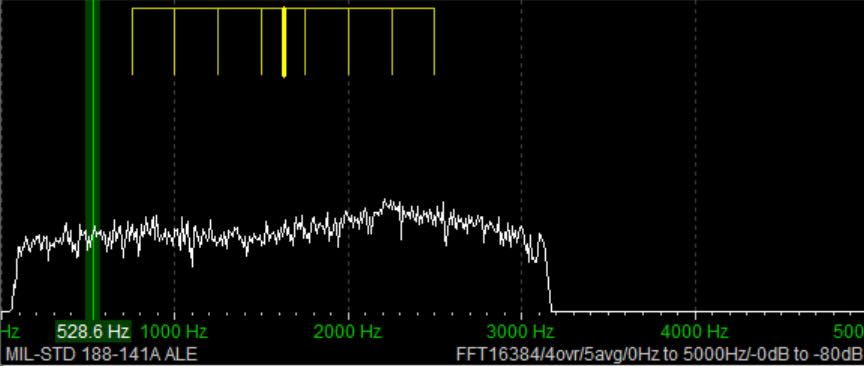

The key to the system is a piece of software called the ALE controller. At periodic intervals, the ALE controller at a particular station, say PLA, will loop through the frequencies and send a “sounding” out on each one. That’s just a short digital identification burst saying “This is PLA!” Here’s a recording of an ALE sounding.

That’s not the kind of signal that anyone would enjoy listening to all day. Fortunately, no human being has to do that. Instead, all the other controllers in the network are monitoring every frequency and automatically make note of how well PLA is received (or not) on each channel. Now, if someone at Offutt Air Force Base needs to send a message to Lajes, they just go to their ALE controller and enter “PLA.” The system will select the best frequency to use based on the most recent observations. That’s the basic explanation. If you want to understand more, see the links at the bottom.

Monitoring ALE

You can’t DX ALE with your ears. A computer program has to do it for you. There are several hobby programs that do the job, and I’m going to look at two of them. The first one will get you started, and the second one will take your ALE DXing to the top.

I began with Sorcerer, a free program that decodes several dozen digital modes. See the links below for downloading. The program doesn’t need to be installed. Just unzip the file and place the executable in a suitable location. Next, you need an SDR and an SDR application. I prefer SDR-Console for digital work, but any SDR program will work if you can feed the audio into a virtual audio cable. And that’s the other thing you need – a direct audio connection from the audio output of your SDR application to Sorcerer. There are several similar products available, but I recommend VB-Cable. Your first VB-Cable is free, and you only need one to run Sorcerer. If you want to expand, you can buy more VB-Cables later.

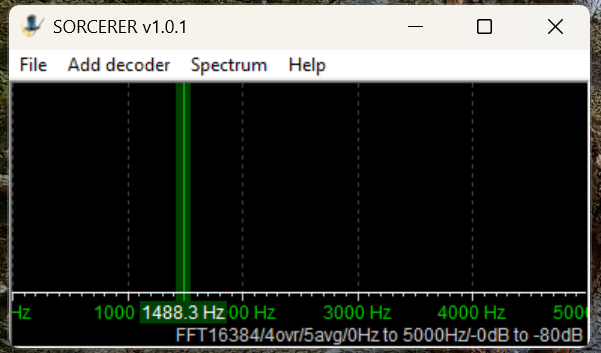

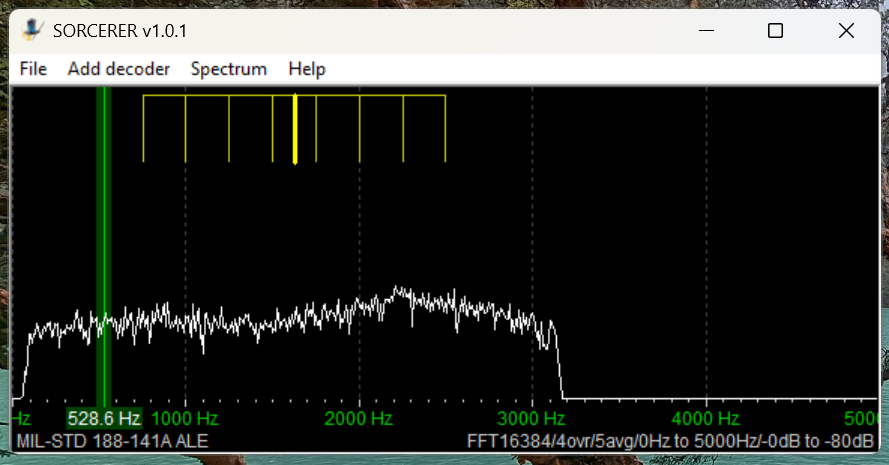

Here’s the main window that opens when you start Sorcerer.

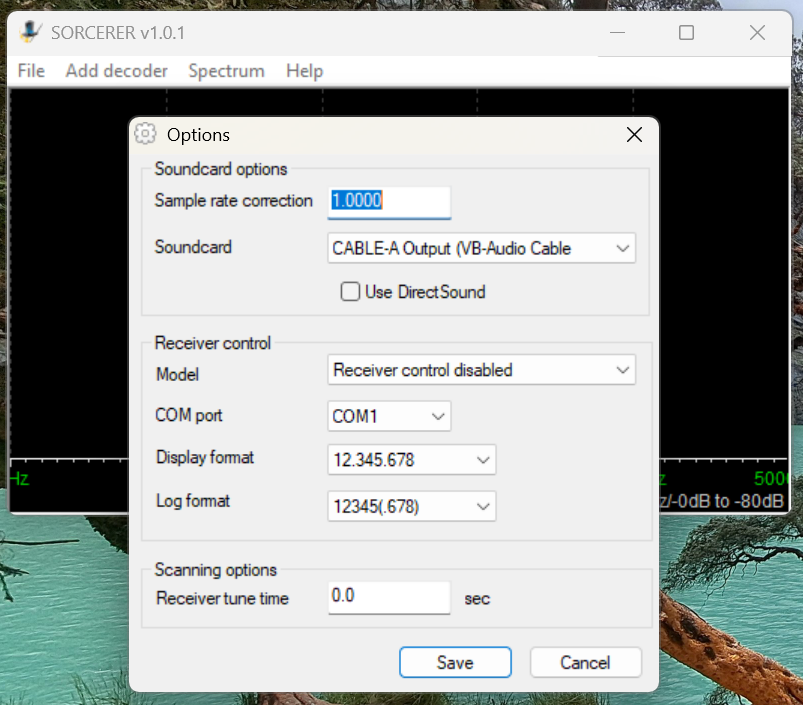

The first time you use Sorcerer you will need to connect it to your VB-Cable. On the menu select File then Options. Find the cable under the Soundcard list and save.

The first time you use Sorcerer you will need to connect it to your VB-Cable. On the menu select File then Options. Find the cable under the Soundcard list and save.

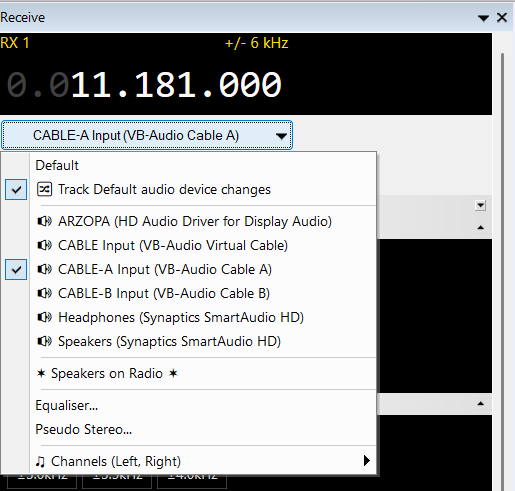

Open your SDR application and tune it to 11181 kHz. Set to USB mode with a filter value of around 2.8 kHz. That is one of the most heavily used frequencies by US Air Force bases around the world. Wherever you are, something should be received. Next, set the audio output of your SDR application to go to VB-Cable. In SDR-Console that’s done by a drop-down box under the current frequency. Next, slide the volume level all the way up.

Open your SDR application and tune it to 11181 kHz. Set to USB mode with a filter value of around 2.8 kHz. That is one of the most heavily used frequencies by US Air Force bases around the world. Wherever you are, something should be received. Next, set the audio output of your SDR application to go to VB-Cable. In SDR-Console that’s done by a drop-down box under the current frequency. Next, slide the volume level all the way up.

Now go back to Sorcerer and confirm you are getting audio from the SDR application.

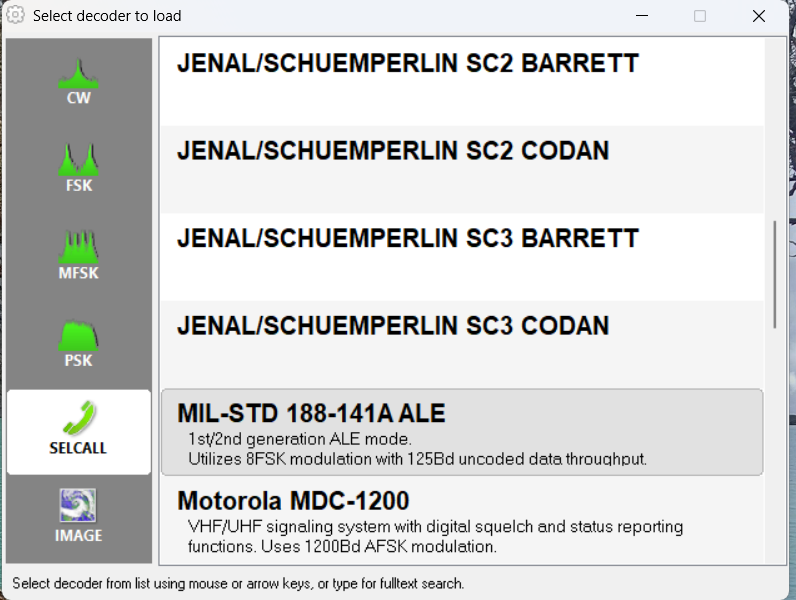

Now select Add Decoder from the top menu in Sorcerer. Then select SELCALL on the left side and scroll down and double-click to select MID-STD 188-141A ALE from the options.

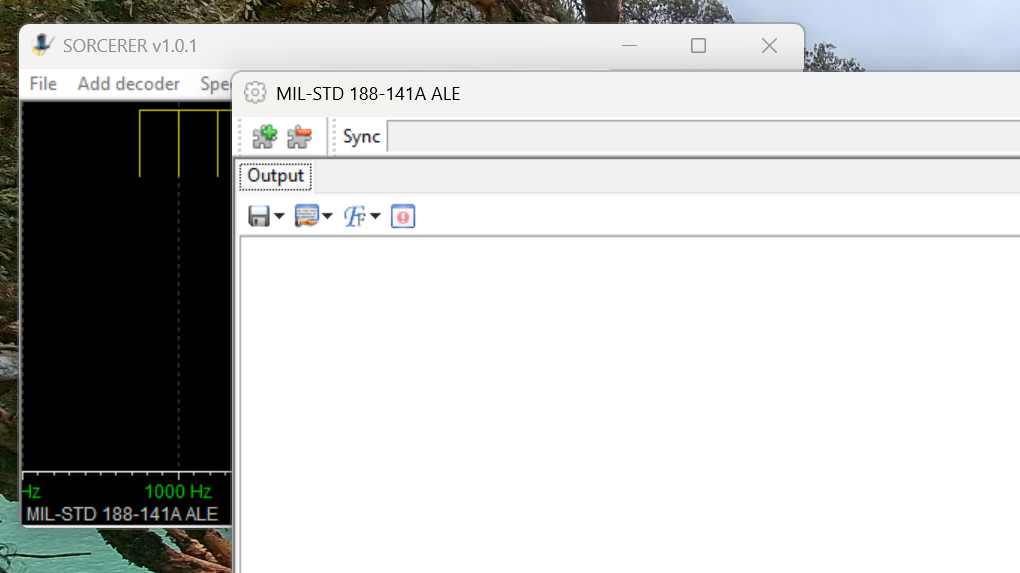

That will open a large decoder window, which you can resize as needed.

Now, go get a cup of coffee and come back in about thirty minutes.

Sample Sorcerer Output

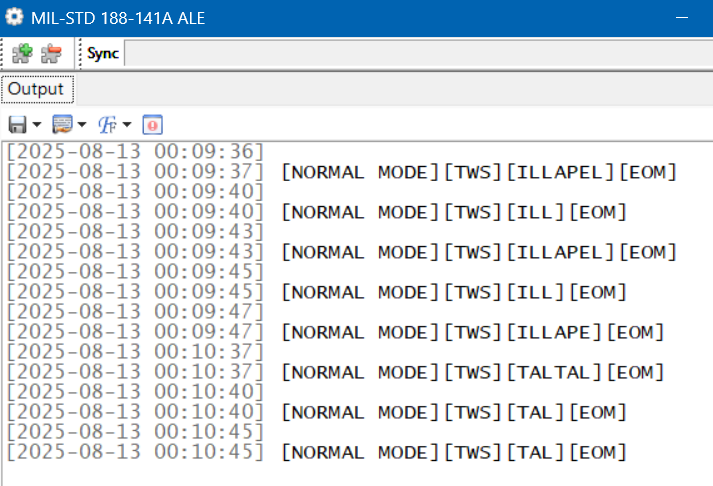

Let’s take a look at some sample output from Sorcerer. These loggings were made on 7915 kHz, a frequency used by the Carabineros (National Police) in Chile. First, Sorcerer shows the time and date the decoding was done per the current time on the laptop. If you are monitoring live, those are the correct date and time of the reception. For the record, I was decoding from SDR spectrum recordings in these examples, so the times and dates are not the real ones. (I got the real ones from the spectrum recordings.) TWS stands for “This Was” and EOM for “End Of Message.” ILLAPEL and TALTAL are the station identifications, which in this case correspond to two Chilean cities. Note that sometimes the end of the ID can be cut off if reception isn’t clear.

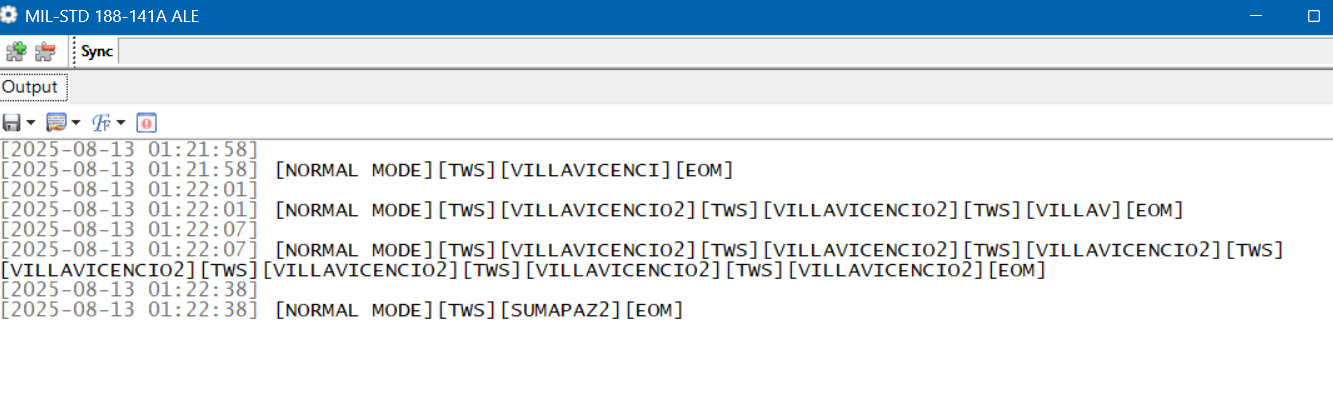

These next loggings are from the national police of Colombia on 7560 kHz. Villavicencio is a city east of the Andes, and Sumapaz is a national park in the remote mountains south of Bogotá.

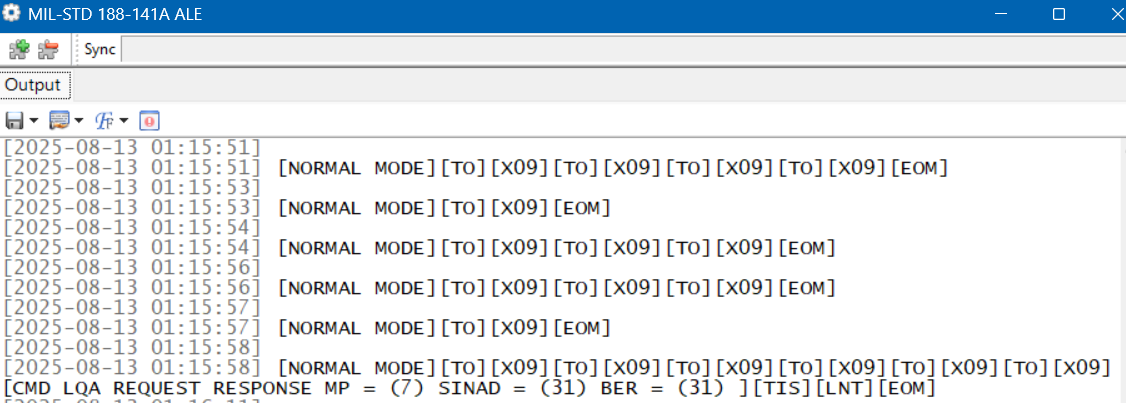

Here is a string of loggings on 7527 kHz, a frequency used by the US Coast Guard and other US government agencies. But here we have a TO, which means someone is trying to call X09. That happens to be a C-27J Spartan, a medium-range surveillance aircraft used by the US Coast Guard. Who’s doing the calling shows up in the final line. TIS (“This Is”) is a variation on TWS. LNT is the identification for CAMSLANT, the big US Coast Guard station in Portsmouth, Virginia.

Here is a string of loggings on 7527 kHz, a frequency used by the US Coast Guard and other US government agencies. But here we have a TO, which means someone is trying to call X09. That happens to be a C-27J Spartan, a medium-range surveillance aircraft used by the US Coast Guard. Who’s doing the calling shows up in the final line. TIS (“This Is”) is a variation on TWS. LNT is the identification for CAMSLANT, the big US Coast Guard station in Portsmouth, Virginia.

The Limits of Single Frequency Monitoring

DXing live and monitoring one highly active frequency at a time with Sorcerer makes for a good introduction to ALE. However, if you just stick to monitoring easy frequencies like the USAF ones, you’ll get a lot of logs, but it won’t take long until you feel as if you’ve gotten everything. There are hundreds more ALE frequencies out there, such as the Chilean and Colombian police ones. But those are less active and might only be received at your location when conditions are just right. If you go after those by live monitoring with your SDR parked on a single frequency, you’ll spend a lot of days without getting a single hit.

What is needed is a way to cast a wide net to catch all the activity in a particular band. The idea I came up with was to use the Spectrum Analyzer feature of the SDR-Console program. See my article on this highly useful feature for an understanding of how this works.

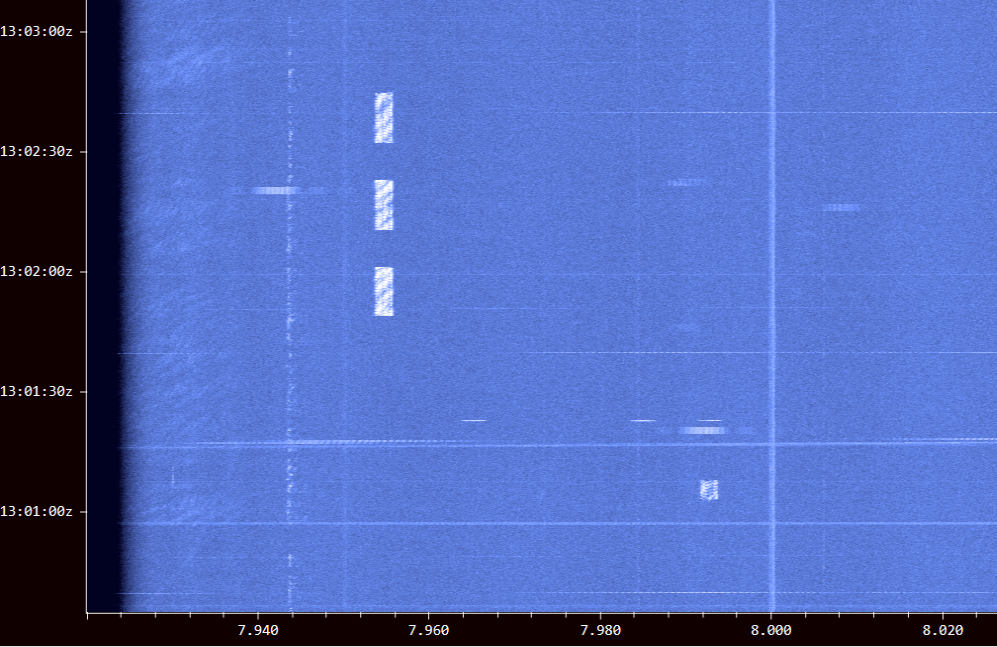

Using an Airspy HF+ Discovery, I would make several hours of spectrum recordings and then use the Spectrum Analyzer to visually find the ALE signals. Here’s a string of three long ALE bursts on 7953 kHz and a single weaker one on 7991 kHz. (Some other digital modes look the same on screen.)

I just had to click on a signal to play it into Sorcerer to get the ID. The process worked really well, and I found a lot of stations this way. But it was also tedious and time-consuming. I wanted something better … something that did the hard work for me. That’s what technology is for, right?

Stay tuned for Part Two …

Links

- Sorcerer Download. Be sure to only download from this link and not from one of the many public download sites. Some years ago there were instances of Sorcerer infected with malware on public sites: https://www.kd0cq.com/2013/07/sorcerer-decoder-download/

- VB Cable Download. Note, it is also possible to use Sorcerer by feeding the audio output from a traditional receiver into the audio input of a laptop. https://vb-audio.com/Cable/

- Wiki Article on ALE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automatic_link_establishment

Oops, here is the link:

https://www.udxf.nl/USAF-HFGCS.pdf

Don,

Here is another good source of ALE descriptions and frequency lists. It is also everything else that is Utility shortwave. It seems that I already had this software installed on my PC but had never tried listening to these frequencies. Surprising results.

Station is a SDRplay RSP-dx-R2 using an old Radio Shack 2mtr. discone antenna. i normally use this for monitoring the UHF military air band. Amazing results on HF. Here are some stations I “heard” in just a few hours today. Thanks so much for bringing this up.

Randy

N5SVW

[2026-02-10 18:05:45] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:46]

[2026-02-10 18:05:46] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:47]

[2026-02-10 18:05:47] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:48]

[2026-02-10 18:05:48] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:49]

[2026-02-10 18:05:49] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:49]

[2026-02-10 18:05:49] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:50]

[2026-02-10 18:05:50] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:51]

[2026-02-10 18:05:51] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:52]

[2026-02-10 18:05:52] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:52]

[2026-02-10 18:05:52] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:05:53]

[2026-02-10 18:05:53] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:34:44]

[2026-02-10 18:34:44] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][EOM]

[2026-02-10 18:34:46]

[2026-02-10 18:34:46] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][EOM]

[2026-02-10 19:01:06]

[2026-02-10 19:01:06] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][EOM]

[2026-02-10 19:01:10]

[2026-02-10 19:01:10] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][TWS][PLA][EOM]

[2026-02-10 19:33:58]

[2026-02-10 19:33:58] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][TWS][MCC][EOM]

[2026-02-10 20:04:51]

[2026-02-10 20:04:51] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][EOM]

[2026-02-10 20:04:54]

[2026-02-10 20:04:54] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][TWS][HAW][EOM]

[2026-02-10 20:06:15]

[2026-02-10 20:06:15] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 20:06:16]

[2026-02-10 20:06:16] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][TWS][JNR][EOM]

[2026-02-10 20:31:22]

[2026-02-10 20:31:22] [NORMAL MODE][TWS][PLA][EOM]

OK, this has me interested. I’ve installed the software, and have received a number of MIL-STD 188-141A ALE transmissions, but they are very cryptic. Is there a source on the internet to interpret who is sending and recipient? Don, you seem to know what the codes mean. That would also be very handy to know. Source? Also, for civilian aircraft, what parameters are used to decode the HF SELCALs? So far, I haven’t figured out how to do this. I assume that it’s in the TONE SELCAL section, but what Mode? 73, and thanks!

More details on resources in part three of the series.

Bravo, Don! I took up the DSC challenge over a year ago now, and have been loving it. LOTS and .lots of traffic on the several DSC frequencies all over the world. Now, I’m very interested in doing the SELCAL thing. I hadn’t previously found a free program to accomplish this. Now, can I decode commercial aircraft traffic SELCALs in the same way?

Good stuff! I’ve set a radio on the recommended frequency to see what I can pick up. Looking forward to Part 2!

ALE decode is also built into KiwiSDR.

Rich,WD3C

Wow, Don, I’ve been wanting an article like this for some time.

As Bill and Ted would say: “EXCELLENT!”

Can’t wait for part II.

Cheers, Jock