The following announcement was shared by Loyd Van Horn of DX Central:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

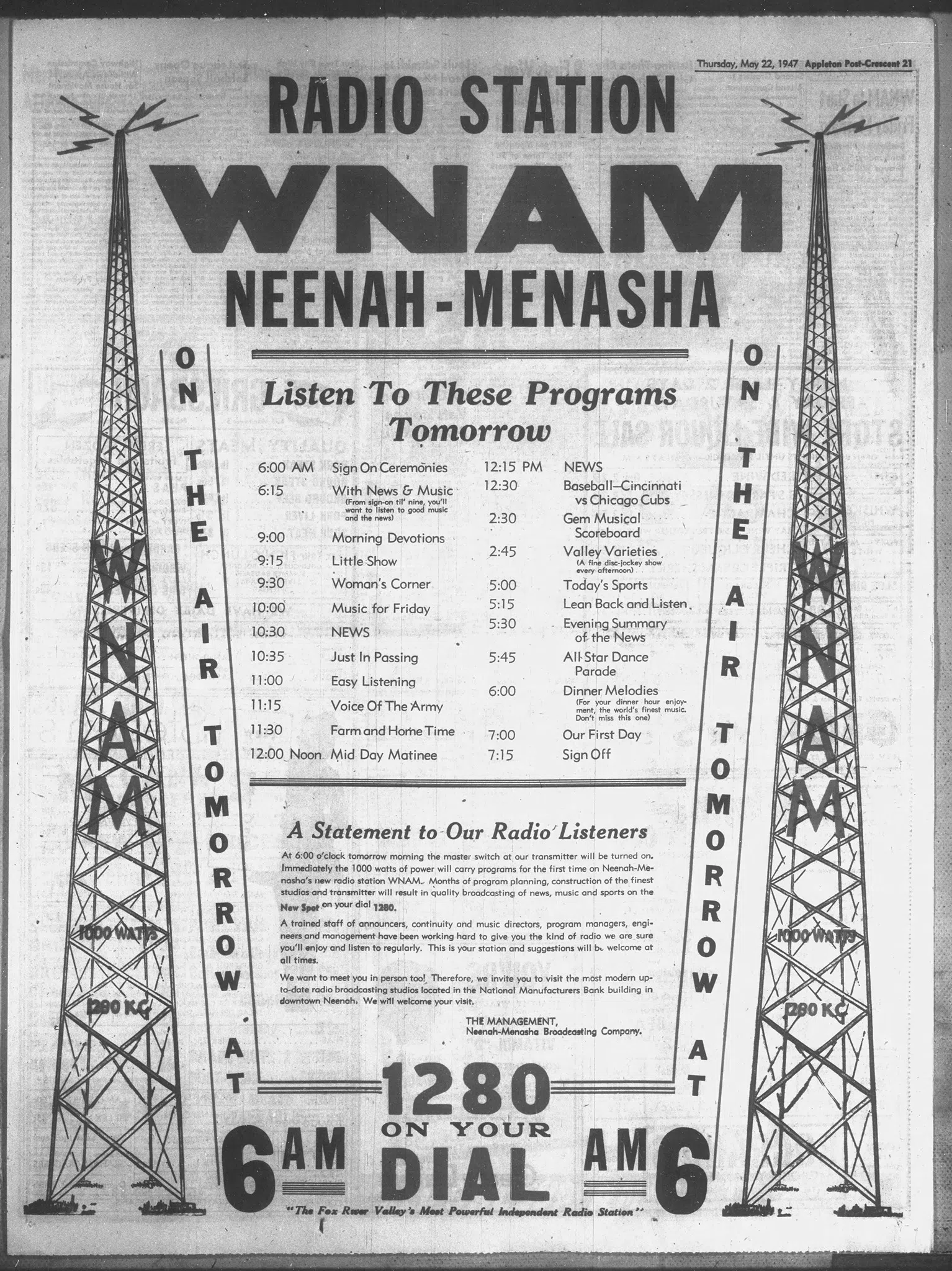

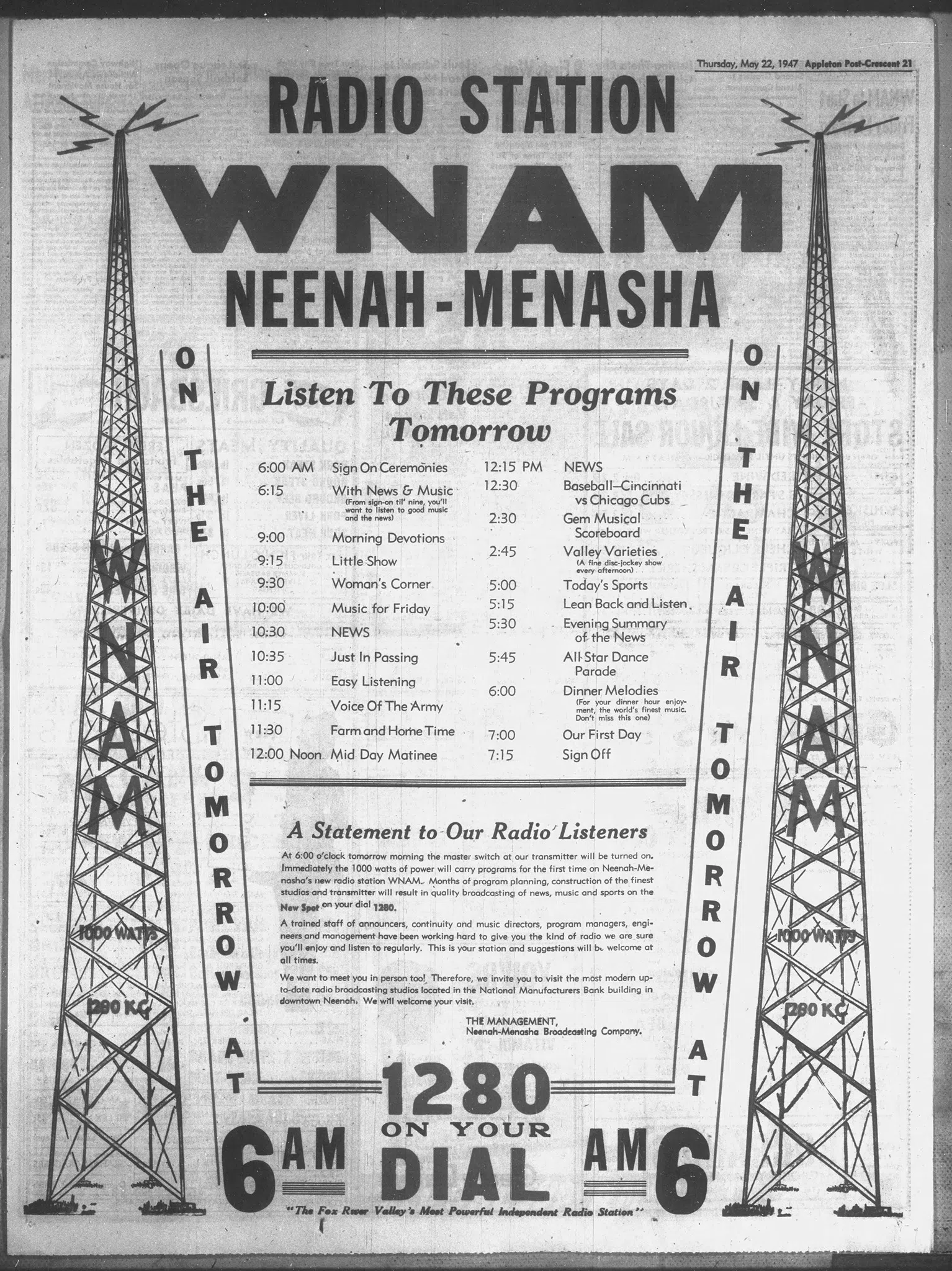

1280 – WNAM DX Test Announcement

Dec 27, 2025

The Courtesy Program Committee (CPC) of the National Radio Club (NRC) and the International Radio Club of America (IRCA) announces a special DX Test for distant listeners for radio station WNAM on 1280 kHz in Neenah-Menasha,WI. The test is scheduled for Tuesday, December 30th and Wednesday, December 31st starting at Midnight local Central Standard Time through 5:05 AM Central Standard Time (This equates to 0600 to 1105 UTC on 30 December and 31 December).

This test is scheduled to run for 2 minutes after ABC News at the top-of-the-hour each hour from Midnight to 5am local Central time. ABC News runs from :00-:03 after the hour. The DX Test will run from :03-:05 after the hour, each hour of the window.

These test transmissions are being broadcast in conjunction with the final days of broadcast of WNAM. WNAM is scheduled to cease broadcast operations at 11:59 PM Central Time on December 31st.

These test transmissions are a way to honor the history of WNAM in its service to the community as well as provide an opportunity for DXers to hear WNAM one last time – or possibly the first time!

The test will consist of an assortment of classic station jingles, sweep tones, voice IDs, morse code and other sounds.

WNAM will be operating at their daytime power/pattern for the duration of the test events.

In addition, listeners/DXers are invited to tune in WNAM’s special 3-hour farewell broadcast on Wednesday, December 31, starting at 9:00 PM Central Standard Time. This will include a “recreation” of the station’s glory years as “Blue 128” complete with airchecks from previous on-air staff.

RECEPTION REPORTS & QSL REQUESTS

All reception reports will be verified through the station directly with a special QSL that was developed for the occasion. Reception reports along with MP3 recordings or .MP4 video recordings of your reception should be emailed to:

[email protected]. Please be sure to use the subject line: “WNAM 1280 DX TEST RECEPTION REPORT.”

The following are recommendations are in effect in order to expedite processing and receive a QSL verifying your report:

-

- Reports via email only – this is required. An MP3 file attachment of your reception (best reception) or an MP4 video clip are preferred. While written descriptions will be considered along with the recording, they may not suffice alone for verification.

- Reports must be submitted within 30 days of the test.

- The report must include your name, location, and return email address, clearly grouped together at the top of the verification request.

- Please also include a description of your receiver, antenna, and any interference noted.

- If you use a remote SDR to receive the test, you must clearly indicate that in your verification request. We will only accept one such report per DX’er. You cannot log the test on multiple remote SDRs and request multiple verifications.

The IRCA/NRC CPC would like to thank the owners and staff of WNAM}, Steve Edwards and CPC member Loyd Van Horn for helping to arrange the test.

Good luck to all DXers!

About the CPC

The Courtesy Program Committee (CPC) is a cross-functional group comprised of members of both the National Radio Club (NRC) and International Radio Club of America (IRCA) for the purpose of coordinating and arranging DX Tests with AM radio stations. These DX tests both allow radio stations to conduct valuable equipment tests on their transmitter and audio chain as well as enable DX hobbyists to receive the testing station from greater distances than would normally be possible. The CPC membership consists of: Chairman Les Rayburn, Paul Walker, George Santulli, Joe Miller and Loyd Van Horn.

For radio stations interested in coordinating a DX test with the CPC, please visit the following Web site for more information:

https://amdxtest.blogspot.com/

For more information on the types of content heard during a DX test, the video “An introduction to DX Tests” is available at DX Central:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NQX_zmEC4fY