The Edward R. Murrow Transmitting Station Control Room

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributors, Dennis, Eric, and Michael who share the following story from Radio World. Please note my comments below following a short excerpt from this piece:

OTTAWA — During the height of the Cold War (1947–1991), the shortwave radio bands were alive with international state-run broadcasters; transmitting their respective views in multiple languages to listeners around the globe.

The western bloc’s advocates were led by the BBC World Service, and included Voice of America, Radio Liberty/Radio Free Europe, Radio Canada International and a host of influential European broadcasters. The eastern bloc’s de facto team captain was the USSR’s Radio Moscow (with its unique hollow, echoing sound), supplemented by broadcasters in Soviet satellite countries (like East Germany’s Radio Berlin International) and allies like Fidel Castro’s Radio Havana Cuba.

Then 1991 arrived, and the Cold War apparently ended with the fall of the Soviet Union and the destruction of the Berlin Wall.

In the seeming peace that followed, many governments no longer saw the sense in spending millions on multi-megawatt transmitters and vast antenna farms to keep broadcasting their messages globally.

The leader among them, the BBC World Service (BBCWS), trumpeted the web and webcasting as modern, cost-effective alternatives to expensive shortwave broadcasting (along with satellite radio and leasing local FM airtime in the countries they used to broadcast to). This is why the BBCWS ceased shortwave transmissions to North America and Australia in 2001 and Europe in 2008, while retaining SW broadcasts in less-developed parts of the globe.[…]

The full article is available here and quite a good piece exploring how the Internet has had an impact on shortwave radio broadcasting.

I, along with a number of fiends in the shortwave community–Bob Zanotti, Jeff White, Colin Newell, and Ian McFarland to name a few–we’re quoted in this piece.

As with most any published piece, quotes and statements are trimmed and edited to fit the print space. If you read the full article, you will have noticed some quotes from me. Here’s a larger portion of my full statement for this piece:

Most audience analysts agree that the number of shortwave listeners has been on the decline at the same time Internet access has been on the rise. Moreover, shortwave listener numbers are hard to quantify due to the very nature of anonymous listening; no one can truly “track” a shortwave radio listener. On the other hand, there is nothing anonymous about those who listen to or watch Internet content–not only can the audience be measured by numbers, but a much deeper and more invasive set of data can be gleaned from an online audience. Thus the decline in shortwave also denotes a loss of anonymity on the part of the listener.

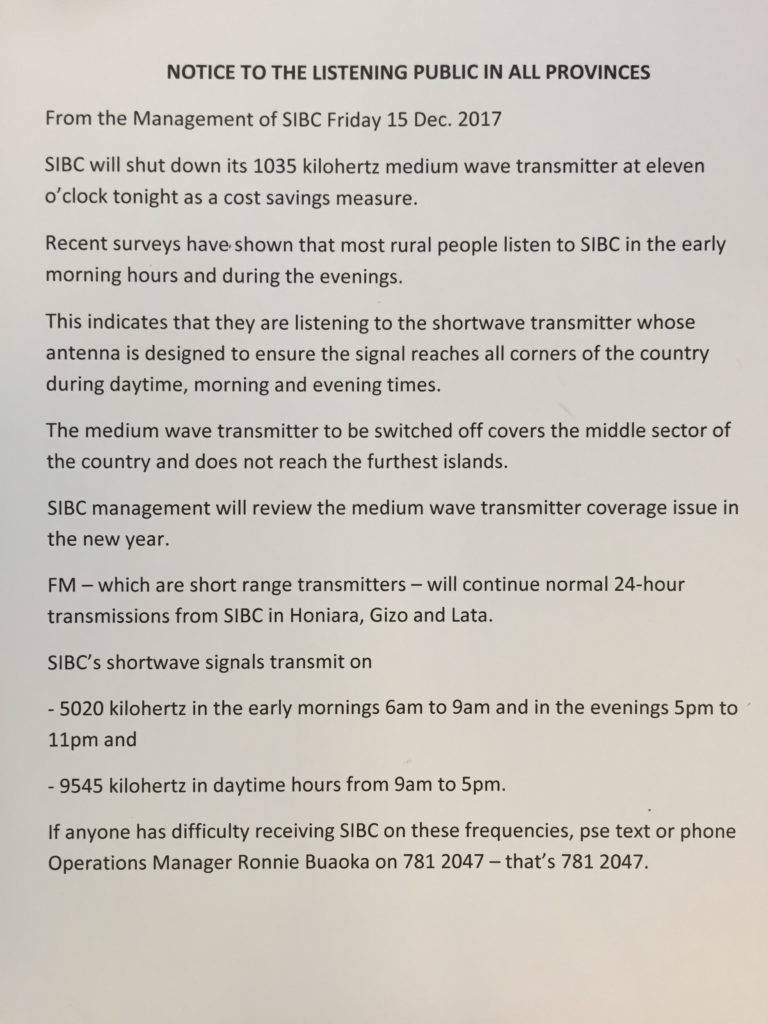

This is not to say there aren’t shortwave listeners. A significant number of listeners are radio enthusiasts/DXers who appreciate the shortwave medium. But perhaps more meaningfully, shortwave listeners are those living in rural and remote parts of the world who benefit from the instant, free, and anonymous information shortwave provides.

At Ears To Our World, we received this photo from a school in rural Tanzania in June 2019. The teacher has been using one of our self-powered shortwave radios to listen to news and improve language skills.

Some broadcasters effectively target both of these audiences. Large government broadcasters, however, have always tried to reach the “influencers” in a country–those who might eventually help guide a country’s policy and international relationships. And the great majority of these influencers, according to audience research, have moved to social media and the Internet as a source of information.

Note that I received the photo above in June. At Ears To Our World, we still work with communities that appreciate the accessibility of radio. Perhaps our partners are more the exception than the rule, but there are still those who benefit from radio–especially those living in rural and remote areas. Where large government shortwave broadcasters are pulling out of the scene, often community-driven stations are taking their place. We’ve been working with Radio Taboo in Cameroon, for example, and they are an amazing case in point.

As a radio enthusiast, I’ll also add that I love the homegrown nature of shortwave broadcasting these days. As private broadcasters have a larger market share of the airwaves, individuals have an opportunity to buy their own broadcast time and produce amazing, unique shows like VORW, Free Radio Skybird, Encore, From the Isle of Music and Uncle Bill’s Melting Pot. These are just a few examples–if you’d like more, just check out the latest edition of Alan Roe’s guide to music over shortwave.

Do you enjoy the SWLing Post?

Please consider supporting us via Patreon or our Coffee Fund!

Your support makes articles like this one possible. Thank you!