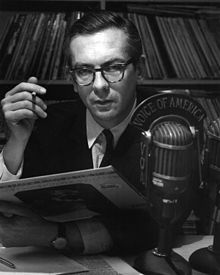

(photo: BBC World Service)

An Antarctic glaciologist, Burmese monk, communications professor and a Somalian tell their shortwave radio stories in this article posted by the BBC World Service in honor of 80 years of shortwave radio broadcasts. In my opinion, these stories are very much representative of the power of shortwave radio and why, for many parts of the world, it is still vital. Though this article focuses on a look into the past, there are still many parts of the world that have no access to the internet, nor reliable electricity and/or their people live under repressive regimes. Shortwave radio offers a lifeline of information. Shortwave listening habits are not traceable or trackable (like they are over the internet) by those in power. The story below, by a Burmese monk, could stand as an example.

(Source: BBC World Service)

[…]The BBC has been an integral part of my life for over two decades now – I believe I haven’t missed a single transmission in all those years. I even kept a diary of all broadcasts from 1988 to 2003, recording all new staff who joined in those years and their first ever broadcast.

I started listening to the BBC Burmese Service in 1988 when the whole country rose up against one-party rule.

I was living in western Burma’s Rakhine State, teaching Buddhist scripture to the student monks. I was fascinated by the BBC’s coverage of the news and was much impressed that the news I heard on BBC turned out to be exactly what was happening in the country.

I was a well-informed and knowledgeable monk, partly because of the BBC. The BBC, because of its reporting on Burma, was much hated by the military authorities and people had to secretly listen to it within their own homes. But luckily for me, I had my own monastery then and could listen to the broadcasts relatively undisturbed.

Then I left for India for further studies but continued to listen. On my return to Burma, I moved to Rangoon, the then capital and stayed at a monastery on the suburbs of the city. Rangoon was a hotbed of activism against military rule and the military government openly practised a “divide and rule” policy. People were suspicious of each other and that distrust spread to the monasteries as well.

The other monks in the monastery disapproved of my listening to the BBC, because they feared government reprisals, and some even said I was an “informer” providing information to foreign broadcasters. They dubbed me a “reporter monk”.

I took more precautions but never stopped listening. I would take my transistor radio and go outside to the farthest corner of the monastery compound, away from other monks, at the times of the broadcasts.

Every day I learned something from the radio. My morning teaching lessons start only after the BBC morning programme and I do my nightly prayer after the evening programme.

My radio is set at the frequencies on which the BBC Burmese broadcasts and I usually tune in a few minutes before the programme starts. I don’t want to miss anything. When the weather is bad, it takes more dedicated effort to tune into the shortwave signal, but I don’t mind that.

Some people frown on monks listening to the BBC. But I believe my life is enriched by it. The BBC has become a very important part of my life and I will continue listening to it until the end of my life. As Buddha has taught, we living beings must face the truth and bring about the truth. I believe the BBC is earning this merit every day by sharing the truth with millions of listeners.[…]

Read the BBC World Service article in its entirety here. I have filed this article under our ever-growing tag “Why Shortwave Radio?”

David Goren,

David Goren,