Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Don Moore–author of Following Ghosts in Northern Peru–for the following guest post:

The Rarest DX?

By Don Moore

In mid-October I received an invitation to attend the annual DXpedition in Cappahayden, Newfoundland with Jean Burnell, John Fisher, and Jim Renfrews. It didn’t take long for me to say yes. Newfoundland is one of the best places in the world to DX from and all kinds of amazing stuff has been heard there. I was excited at the prospect of great medium wave DX and being able to log low-powered European private and pirate shortwave broadcasters.

But something else was at the top of my try-for list. One of my many DX interests has always been logging coastal marine stations in the 1600 to 3000 kHz range. In preparation I started checking online sources to update my spreadsheet of schedules. In going through a recently added section on Marine Broadcasts in the DX Info Centre website I came across listings for twice-daily weather broadcasts from Hopen Island on 1750 kHz and Bjørnøya (Bear Island) on 1757 kHz.

I didn’t remember ever seeing anything about broadcasts from these remote islands in the Norwegian Arctic before. Were these stations actually on the air, I wondered. And if they were, could I hear them in Newfoundland?

HOPEN ISLAND

Hopen is a remote and seldom-visited island six hundred kilometers due north of continental Norway and one hundred kilometers south of the Svalbard Archipelago. The island extends for thirty-eight kilometers from southwest to northeast but is never more than about two kilometers wide. On aerial photos Hopen appears to be a mountain ridge ringed by steep cliffs rising from the sea.

Hopen is a remote and seldom-visited island six hundred kilometers due north of continental Norway and one hundred kilometers south of the Svalbard Archipelago. The island extends for thirty-eight kilometers from southwest to northeast but is never more than about two kilometers wide. On aerial photos Hopen appears to be a mountain ridge ringed by steep cliffs rising from the sea.

The climate is classified as Arctic tundra, which means it’s either cold or very cold all the time. But fish are abundant in the surrounding waters so seals are plentiful and Hopen is home to numerous species of seabirds. It was also once home to a large population of walruses. They were eliminated by hunting in the 1800s but in recent years some have migrated back to Hopen from Svalbard. Polar bears, on the other hand, have gone from common to rare. Until a few decades ago as many as three-hundred bears would cross the ice from Svalbard during the winter to feed on seals. But over the past twenty years the ice pack has diminished and now few bears find their way to the island.

The first humans to see Hopen Island were probably whalers who began to frequent these seas in the late 1500s. The first documented possible sighting was by the Dutch explorer Jan Rijp in 1597. The island probably received its name from English explorer Thomas Marmaduke, who may have visited the island in 1613 and named it after his ship, the Hopewell. In the following centuries Hopen was used as a base for hunting whales, seals, and walruses. Ruins of old huts and kilns for melting the lard can be found scattered around the island.

For over three centuries this region was distant and disconnected from the rest of the world. Then in June 1941 Hitler’s Germany attacked the Soviet Union and that turned the sea lanes south of Hopen Island into a battleground. The best way for the Allies to supply Russia was by convoys through the Barents Sea to Murmansk. German submarines, warships, and aircraft were determined to stop them. After invading Norway in 1940, Germany had ignored Svalbard; it didn’t seem to have any strategic importance. But it’s difficult to conduct warfare in the Arctic without good weather forecasts so the Germans began to establish weather stations in remote parts of the archipelago. Meanwhile the Norwegians, who still controlled parts of the islands, hunted them down with British air and naval support.

In an attempt to outfox the hunters, the Germans decided to establish a weather station in a place that had not yet been involved in the war – Hopen Island. In mid-1943 a U-Boat dropped off four men, supplies, and a transmitter at an accessible point on the eastern coast. Some equipment was lost while ferrying it ashore but enough survived to get the station on the air. After a few months the men were withdrawn but three months later another party of four was landed with more equipment and supplies. These men were still there when the war ended on May 8, 1945. They continued to make weather observations and radio reports until happily surrendering to a Norwegian fishing vessel in August.

(Historical sidenote: In September, 1945 the crew of a remote weather station at Haudegen on Svalbard became the last German unit to surrender in World War Two.)

A few weeks after the Germans were evacuated, the Norwegian Navy took over the Hopen site and the weather station has operated continuously since then. The abandoned German equipment was used for the first winter but new equipment was brought in the following year. In 1947 ownership of the station was transferred to the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, which still operates it.

Hopen Meteo Station has usually been manned by a crew of four. For several decades staff served for one year, from one summer until the following summer. Later that was changed to periods of six-months. This year’s winter crew just started on December 6th.

Over the years the station has changed in many ways from the bare-bones operation first dropped off from a wartime U-Boat. The multi-building complex now includes a large residence with five bedrooms, a garage for the tractor, workshops, water tanks, a warehouse, an exercise room, two diesel generators, and eight tanks holding 120 cubic meters of fuel. There is also a boathouse, a guest house, and, in case some sort of disaster should strike the main building, a second emergency residence with duplicate weather equipment so the crew can continue their work.

And the main work at Hopen is collecting weather data every three hours every day of the year, which means going outside in even the coldest weather. Other tasks include measuring sea ice in season, recording observations of wildlife, watching sensors that monitor the northern lights, and simply doing all the maintenance that is needed to keep the facility running smoothly.

Hopen Island is a remote place and for many years once crews were dropped off their only contact with the outside world was a radiotelephone link to Vardø in mainland Norway. In 1998 a satellite station for fax and data communication was set up at the station, ending their total dependence on traditional radio communication. Ten years later the satellite service was upgraded to give the residents full Internet access. Radiotelephony capability is preserved as a backup.

Hopen has always been a weather station and not a coastal station for marine communications. In earlier years the station did occasionally do some two-way communications with ships on VHF and 2168 kHz. Those were ended about a decade ago and at that time the radio station name was changed from Hopen Radio to Hopen Meteo. They continue to broadcast their daily weather reports at 1103 and 2303 UTC on VHF channel 12 and 1750 kHz medium frequency with 700 watts. A short announcement is made on 2182 kHz just before the broadcast starts.

A satellite view of the complex can be seen on Google Maps by plugging the coordinates 76.5090, 25.0141 into the search bar.

BJØRNØYA

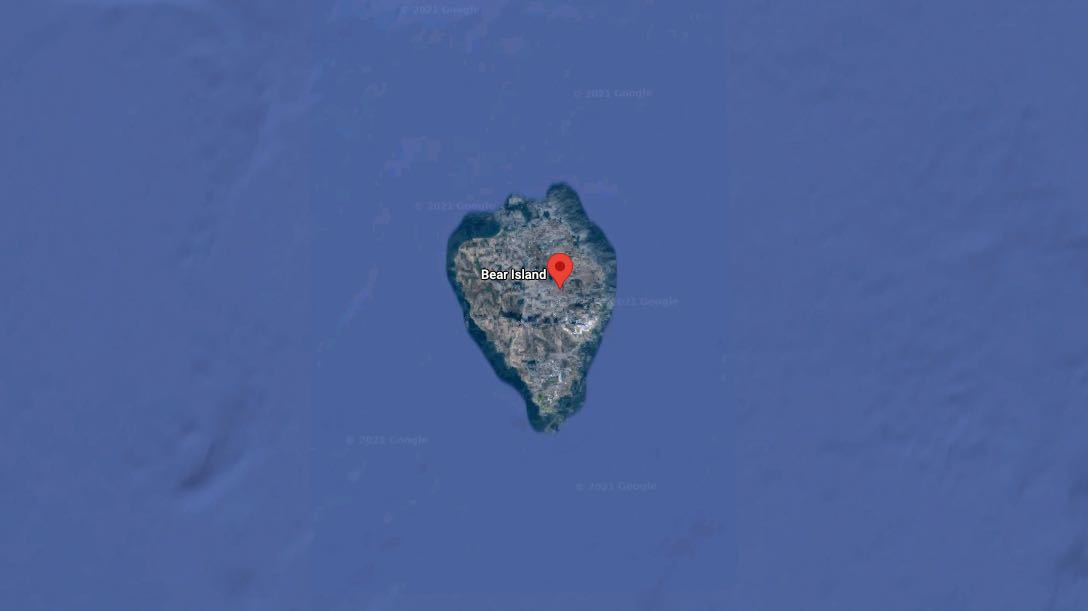

Bjørnøya, or Bear Island, is a heart-shaped island about 270 kilometers southwest of Hopen, which places it about 100 kilometers closer to mainland Norway. Being further west, Bjørnøya benefits more from the north Atlantic current than does Hopen. The annual average temperature is about zero degrees Celsius, which is almost six degrees warmer than on Hopen. Like Hopen, the surrounding waters are filled with fish and the island is home to seals and countless seabirds. According to some studies, Bjørnøya may have the largest colony of seabirds in the northern hemisphere. But, despite the name Bear Island, polar bears have always been rare. Because the surrounding waters are warmer the ice cover seldom extended this far south for the bears’ winter migration.

Bjørnøya, or Bear Island, is a heart-shaped island about 270 kilometers southwest of Hopen, which places it about 100 kilometers closer to mainland Norway. Being further west, Bjørnøya benefits more from the north Atlantic current than does Hopen. The annual average temperature is about zero degrees Celsius, which is almost six degrees warmer than on Hopen. Like Hopen, the surrounding waters are filled with fish and the island is home to seals and countless seabirds. According to some studies, Bjørnøya may have the largest colony of seabirds in the northern hemisphere. But, despite the name Bear Island, polar bears have always been rare. Because the surrounding waters are warmer the ice cover seldom extended this far south for the bears’ winter migration.

It’s thought that Vikings may have reached Bjørnøya but no proof of that has been found. The first known visit was by Dutch explorer William Barents, whose vessel was part of the same expedition that may have first sighted Hopen Island. Barents named his find Bird Island but a later expedition changed it to Bear Island and the name stuck.

Photo by the Bjørnøya Meteorologiske Stasjon

Like Hopen, for several centuries Bjørnøya became a base for whaling and for walrus and seal hunting. England tried and failed to establish a permanent post on the island in the 1600s, as did the Russians a century later. In 1916 the Norwegian company Bjørnøen AS began mining coal on the northeast side of the island and built a small village named Tunheim. They even built a short railroad linking the mine with the shore. In 1918 the company declared ownership over the entire island. Under international law, Bjørnøya had never belonged to any country but because of the mining operation administration of the island was awarded to Norway in 1920.

The coal mine closed in 1925 as Bjørnøen AS couldn’t make a profit. In 1932 the bankrupt company was nationalized and complete ownership of the island passed to the Norwegian government. The company still exists as part of the Norwegian Ministry of Trade and Industry.

The closing of the mine didn’t spell the end of the little village of Tunheim. In October 1918 the company had opened an office to collect meteorological data and a year later installed LJB, the island’s first radio station, using CW for marine communication and to send weather data back to the mainland. The meteorological office and radio station continued to operate after the miners left. Both became property of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute when Bjørnøen AS was nationalized in 1932.

World War Two may have brought radio to Hopen Island, but it ended broadcasting from Bjørnøya. In 1941 the Allies closed the radio station and destroyed everything at Tunheim to prevent the possibility of Germany capturing it and making the island a base. According to some sources the Germans tried to deploy an automated radio station on Bjørnøya in 1941.

After the war ended the Norwegians had the Bjørnøya weather station back on the air by the end of May 1945. The data it collected was important and had been missed. Plans were made for a bigger and better operation, so in 1947 the station was moved to its current location, Herwighamna on the north coast, where there was a better harbor for unloading supplies.

For the next several decades Bjørnøya Radio was a very busy place. In addition to the weather broadcasts the station was a marine coastal station providing round-the-clock CW and voice communications with ships at sea. A minimum of two radio operators had to be on duty at all times, so the station had a large staff. Some years as many as nineteen radio operators, meteorologists, and other workers wintered over. That ended in 1996 when equipment was installed so that two-way communication could be done remotely from the Telenor office on the mainland. Soon after Bjørnøya Radio was renamed Bjørnøya Meteo.

Today Bjørnøya is typically staffed by nine men and women working on six month contracts. Bjørnøya is a larger operation than on Hopen Island so a larger crew is needed. The weather crew has more to do, including deploying weather balloons – two a day in the summer and four a day in the winter. There is a lot of additional equipment that the staff maintains, including Telenor’s remote two-way radio equipment. The radio station, Bjørnøya Meteo, is only a tiny part of the total operation.

The weather reports for both Hopen and Bjørnøya are prepared by the main office on the mainland using data from all the different weather collection points. Scripts are prepared in English and Norwegian and sent to the stations to be read on the air. The reports always start with any storm or gale warnings and then continue to the more routine parts of the forecast. Most sea-going vessels today have satellite capability so the weather broadcasts don’t have the importance they once did. Today they primarily serve as a backup.

Bjørnøya Meteo broadcasts daily at 1005 and 2205 UTC on VHF channel 12 and 1757 kHz medium frequency with 700 watts. A short announcement is made on 2182 kHz just before the broadcast starts. Although they are not used on the air, the call letters are still LJB, the ones originally assigned in 1919. A satellite view of the complex can be seen at coordinates 74.5040, 18.9972.

THE TELENOR STATIONS

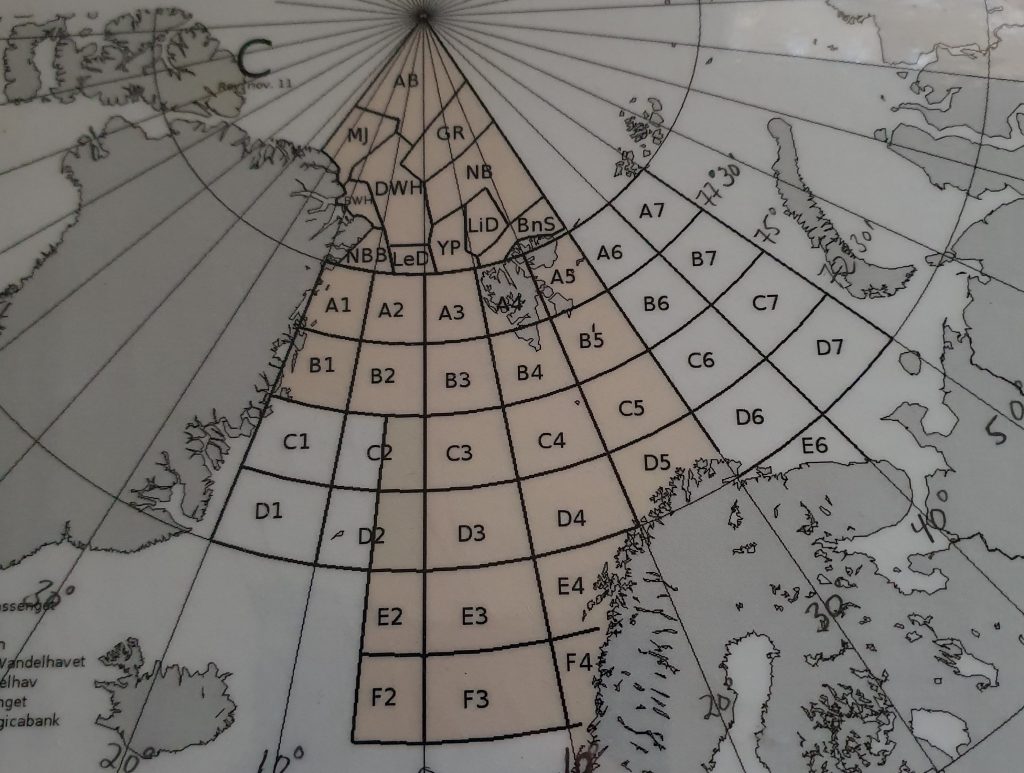

Norway is an important maritime nation and with its long fjords and many islands has thousands of miles of coastline. The Telenor Corporation runs all of Norway’s traditional marine coastal communications stations on VHF and medium frequency (MF) for both two-way communication and marine information broadcasts. Telenor stations on MF are organized into two groups. Norwegian Coastal Radio South includes stations at Floro (1680 kHz), Maroy (1692), Bergen (1728), Orlandet (1782), and Farsund (1785). Norwegian Coastal Radio North consists of five stations on the mainland – Hammerfest (1635), Andenes (1659), Berlevag (1695), Sandnessjoen (1710), and Bodo (1770) – plus Longyearben in Svalbard (1731) and Jan Mayen island (1743) in the Arctic. All these stations use one thousand watts.

Both groups have marine broadcasts every four hours at 0203, 0603, 1003, 1403, 1803, and 2203 UTC. The North network has an additional broadcast at 2303 and the South at 2315. All broadcasts are first announced on 2182 kHz. While those broadcasts are networked, all the stations are independently staffed and may do two-way communication or broadcast local marine information under their own name (e.g. Floro Radio).

LOGGING THE NORWEGIANS

So did I hear Hopen Island and Bjørnøya? Of course, otherwise I wouldn’t have researched and written this article!

So did I hear Hopen Island and Bjørnøya? Of course, otherwise I wouldn’t have researched and written this article!

Every day I used my Elad FDM-S2 to make spectrum recordings around the scheduled times of various marine broadcasts and then checked them out later in the evening and the next morning. The first night I had all five stations of the Telenor South network plus Sandnessjoen of the North group. A few more of the North network stations popped up the next two nights, but still nothing from any of the islands.

Then on November 12th, the fourth night, I checked for Bjørnøya on 1757 at 2205 and there it was. I heard a weak ‘All Ships’ announcement and ID in English and then they began the weather. It was now about two hours after that happened as I was DXing on spectrum recordings. I immediately loaded up the recording for 2300 and started up the list of frequencies. Both Svalbard on 1731 kHz and Jan Mayen on 1743 kHz were there in parallel with other stations on the North network. And there was a weak voice on 1750 kHz. I picked out an ‘All Ships’ announcement at the start but everything else was muddy. Then towards the end the signal got stronger and just before they went off there was a Hopen Meteo ID in Norwegian. In slightly more than an hour I logged all four Norwegian islands plus all the mainland Telenor stations.

Conditions were also good the next two nights so I was able to get three logs of both Hopen Island and Bjørnøya. I sent reception reports with MP3 recordings to both stations and got e-QSLs within hours.

THE RAREST DX?

So how rare are these stations?

The online logs of the Utility DXers’ Forum go back to its founding in 2006 and neither Hopen Island nor Bjørnøya has ever been reported. Nor has Svalbard on 1731 kHz although Jan Mayen was heard once in 2010. Before 2006 the largest utility listeners’ club was the World Utility Network and none of the four frequencies were reported to them between 1995 and 2006. The only other loggings of any of the four frequencies that I could find was of Svalbard 1731 being heard in 2018 and 2019 at the annual DXpedition on Long Beach Island in New Jersey, USA.

I would like to think that I’m the first DXer to have heard Hopen Meteo and Bjørnøya Meteo. In reality, I’m sure they’ve been heard in Scandinavia over the years without the logs getting reported to the larger utility clubs. And I don’t know what DXers heard back in the 1960s or 1970s … or even the late 1940s. However, I will claim the first North American reception in at least a quarter century until proven otherwise.

All these stations are difficult DX. But part of what makes them rare DX is that DXers don’t know about them and no one tries to hear them.

In the 1970s and early ‘80s, the ultimate DX catch in North America and Europe was the Falkland Islands on 2370 kHz with 500 watts. DXers tried night-after-night for the station and, once in a while, it was there. Hopen Island and Bjørnøya with 700 watts on nearby frequencies are the same kind of DX and have channels free of interfering stations. Likewise for the 1000 watt stations of Telenor above 1710 kHz. (The lower frequencies will be blocked by X-band stations in most of North America.)

This kind of DX does require a serious receiver and a good antenna at a quiet listening location. It also requires the persistence to keep trying until the right conditions are there. The same was true of DXing the Falklands four decades ago. All these stations are possible in eastern North America and Europe. Last winter I heard the Telenor stations on 1728, 1782, and 1785 kHz in central Pennsylvania. If I spend time in Pennsylvania this winter I hope to hear more.

So here’s the challenge: Who will be the next North American DXer to hear and report Hopen Island and Bjørnøya?

AUDIO FILES

Pre-announcement for broadcast by Norwegian Coastal Radio North:

Heard in Newfoundland on 2182 kHz on 11 November 201 at 2234 UTC.

Beginning of broadcast by Norwegian Coastal Radio South via the Floro site:

Heard in Newfoundland on 1680 kHz on 9 November 2021 at 2235.

Beginning of broadcast by Norwegian Coastal Radio South via the Bergen site:

Heard in Pennsylvania on 1728 kHz on 22 January 2021 at 2235 UTC.

Bjornoya Meteo heard in Newfoundland on 12 November 2021 at 2205 UTC:

The Bear Island Meteo ID is heard at the beginning just after the ‘All Ships’ announcement.

Bjornoya Meteo heard in Newfoundland on 13 November 2021 at 2209:

An ID is at nine seconds in.

Hopen Meteo heard in Newfoundland on 12 November 2021 at 2308:

An ID is at nine seconds in.

LINKS

Links are in Norwegian unless otherwise noted. Google Translate comes in very handy for doing more than just looking at the pictures.

The official website and blog at Hopen Island. It includes a complete list of all the crews who have served here including the original two German crews.

Some Blogs by former Hopen Island crew members.

An illustrated article about Hopen Meteo with lots of pictures. The rest of the site is about the history of Norwegian coastal stations.

http://www.jankrogh.com/kystradio/lmr/index.html

Occasionally both islands are active on the amateur bands. Here is an English article about one time.

https://trafficlist.altervista.org/hopen-island-svalbard-still-active-with-cs-jw2us/

The official website and blog of Bjørnøya Meteo. They have pictures of all the crews going back to 1959.

Blogs by former Bjørnøya crew members

- http://bjornoya.blogspot.com/

- http://lisesbjornoyaeventyr.blogspot.com/

- http://bjarne.no/

- http://karinseventyr.blogspot.com/2019/

- http://www.djupdal.org/asbjoern/?cat=5

An English article about a recent visit to Bjørnøya

https://theamericanscholar.org/the-barents-sea-land-of-perpetual-night/

An English article about World War Two in the region

https://www.spitsbergen-svalbard.com/spitsbergen-information/history/the-second-world-war.html

Historical Photos of Norwegian Coastal Stations

Really enjoyed this read. The YL and I are visiting Norway next April, will definitely bring my receiver!

Hej. Iam heard bjornoya coastal radio at 2013 year. In st. Petersburg Russia

https://soundcloud.app.goo.gl/ipxU2

Hej. I heard Bjornoya isl in far 2013. From st Petersburg city.

https://soundcloud.app.goo.gl/ipxU2

I heard Bjornoya isl. In 2013 year. In st. Petersburg Russia.

Listen to 10_Jan_2013_0209_1_755MHz.mp3 by ua1ava on #SoundCloud

https://soundcloud.app.goo.gl/ipxU2

Amazing article!

I found that Bear Island is IOTA EU-027 was fairly active but Hopen EU-063 not that much

https://www.dx-world.net/tag/bear-island/

https://www.dx-world.net/?s=hopen

** I might have QSL from JW6BAA Bear Island June 1984 operation, I’ll look for it.

A very nice article.

I stayed 6 months on Hopen Radio in 1994 as a radio officer / met. observer. We sent the weather observations via CW on 425 kHz to Bear Island every 3 hours. It was a memorable stay. 315 different polar bears recorded in our logbook.

I was QRV on ham radio as JW5EBA.

Well written. The KONG HQ (kongsfjord.no) isn’t far away from the Berlevåg 1695 kHz station, and the signal is quite strong (400 or 600 watts while in digital mode)

I wonder if the Norwegians have tried transmitting sea ice maps using DRM?

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1061702

So, perhaps you should add an SDR with DRM decoding to see if there is any DRM data transmissions.

The waterfall display shows DRM signals as being the same intensity over the whole channel width, where as AM has a strong carrier. SSB signals are half the width of an AM channel.

Thanks so much. That was a fabulous article. It reminds me of a wartime Canadian movie about Nazis landing on Newfoundland to establish a weather station, but getting stranded. https://www.imdb.com/video/vi2967061273?playlistId=tt0033627&ref_=tt_ov_vi It has a cast of great actors who all have fun over-acting.

Wow! Great article!

Thank you very much for this inspiring and informational article. I am planning a trip to Newfoundland on motorcycle next summer, and will be doing some DXing. Great preparation material!!!

Be Well,

Ray V

Wonderful catch, great article! Thank you for sharing.

This is a wonderful article, Don! Thank you so much for sharing.

Like you, part of the fun of DXing is understanding historical and geographical context. I really appreciate the time you put into taking us on a journey of how these stations came into being.

I know that Paul Walker in McGrath, Alaska, recently snagged Svalbard’s station, so perhaps he can share details here.

Thank you again–those recordings are superb.

Cheers,

Thomas