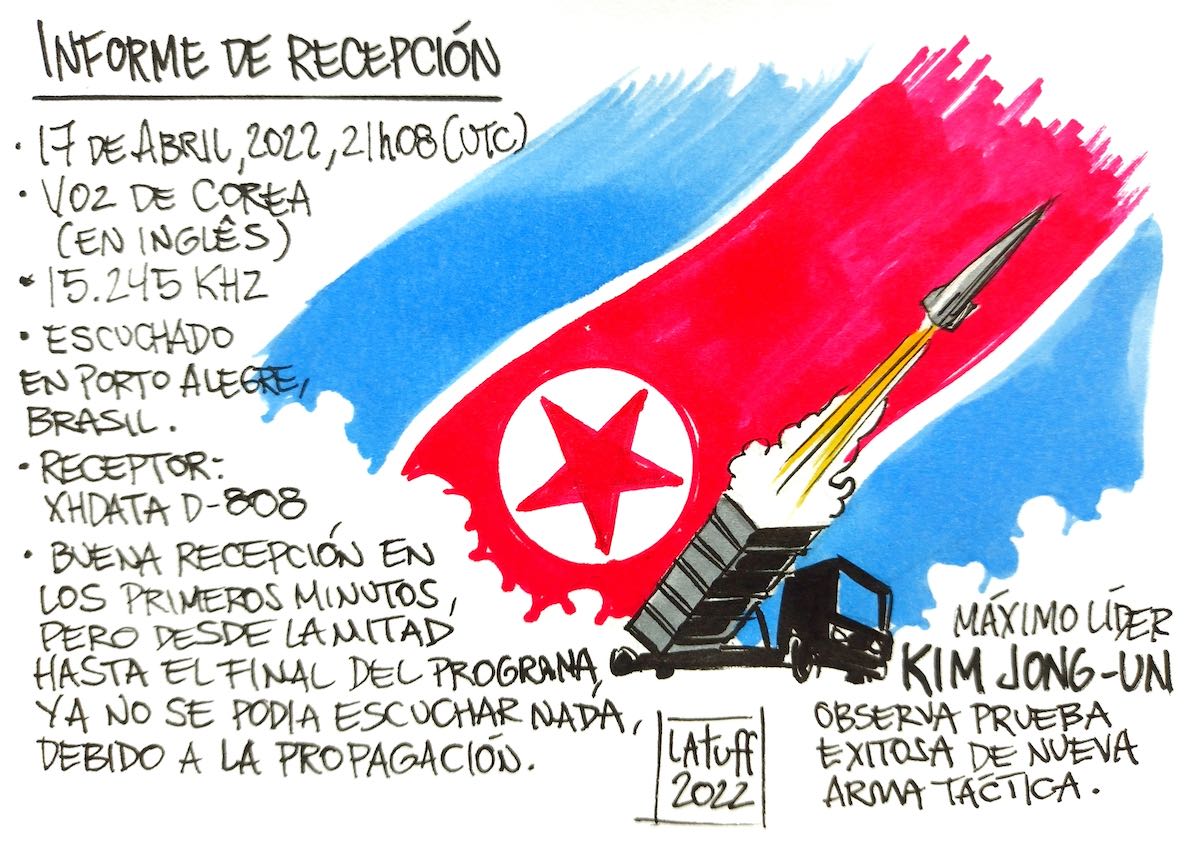

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Jock Elliott, who shares the following guest post:

A real-life shortwave story

By Jock Elliott, KB2GOM

On July 25, 1943, a Royal Canadian Air Force Wellington bomber took off from England to fly a mission over Nazi-held territory in Europe. It never returned to base.

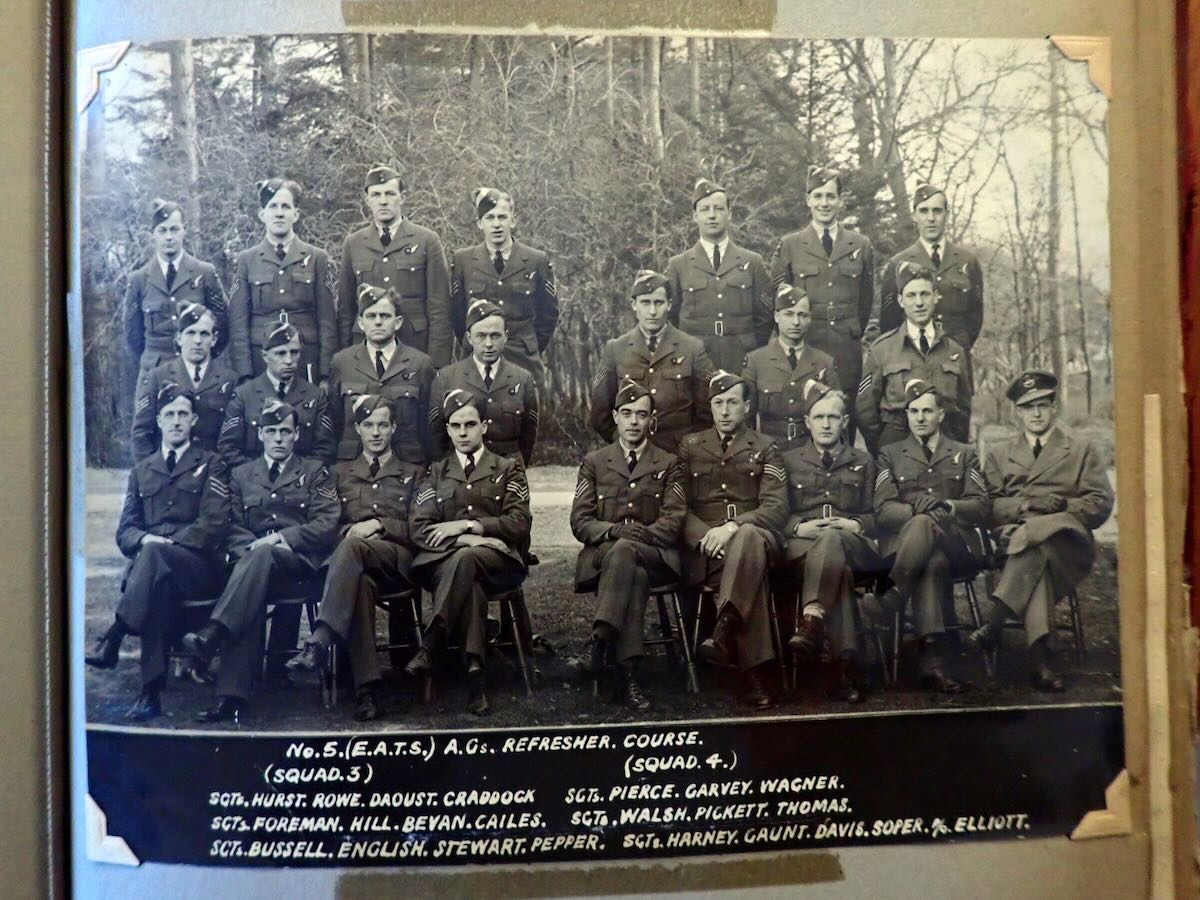

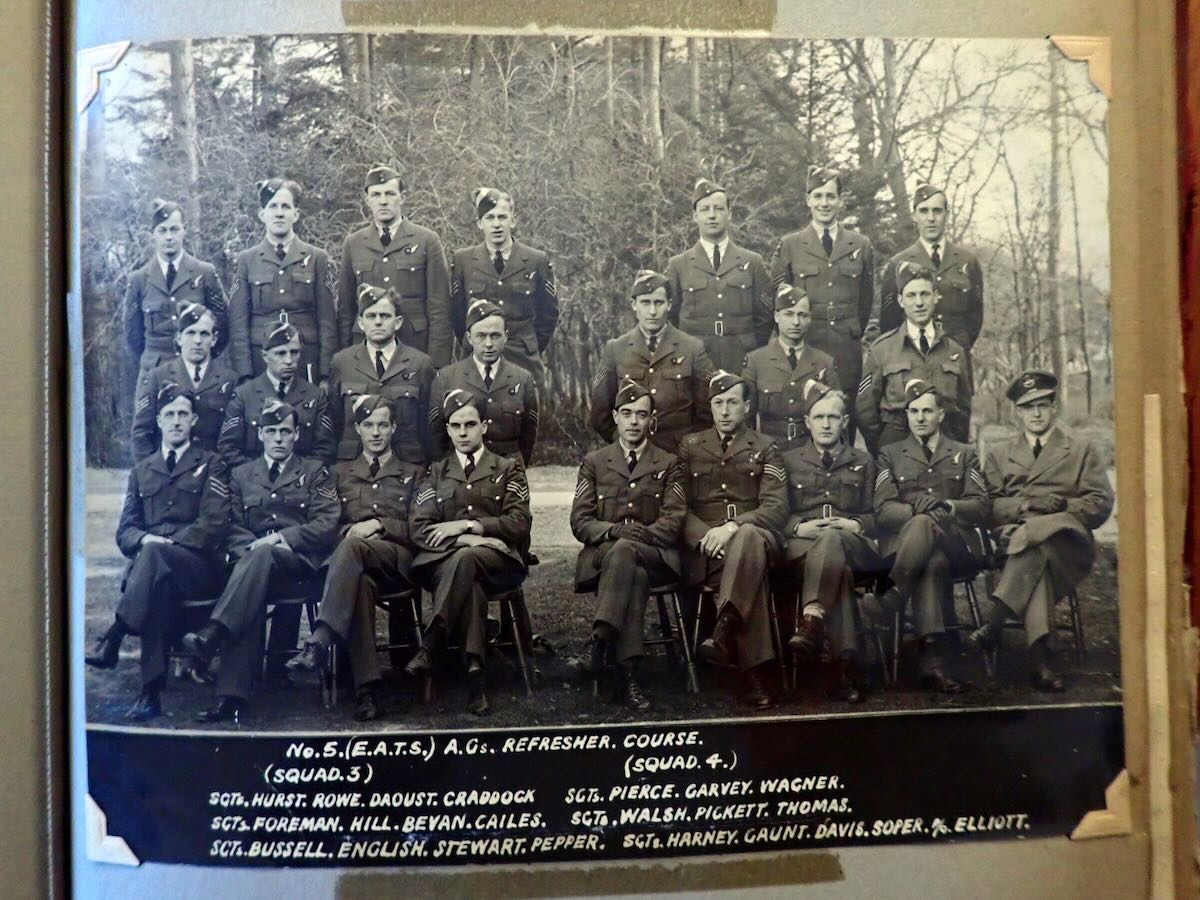

A Wellington aircrew getting ready.

On board was an American Lieutenant, tailgunner on the aircraft. He had flown at least 19 missions, and now his status was unknown.

The office.

On July 30, a letter was sent to his wife. It began:

Before receiving this letter you will have had a telegram informing you that your husband, Lieutenant John Chapman Elliott, is missing as a result of air operations. I regret to have to confirm this distressing news.

John and the air crew took off on an operational sortie over enemy territory on the evening of the 25th July and we have heard nothing of them since. However, it is decidedly possible that they are prisoners of war or are among friends who are helping them to make their way back to this country . . .

Status unknown . . . “we have heard nothing of them since.” An agonizing psychological limbo. Do you mourn or do you hope? How do you live in that middle space?

The exact timing of what happens next isn’t clear, but in September two things happened.

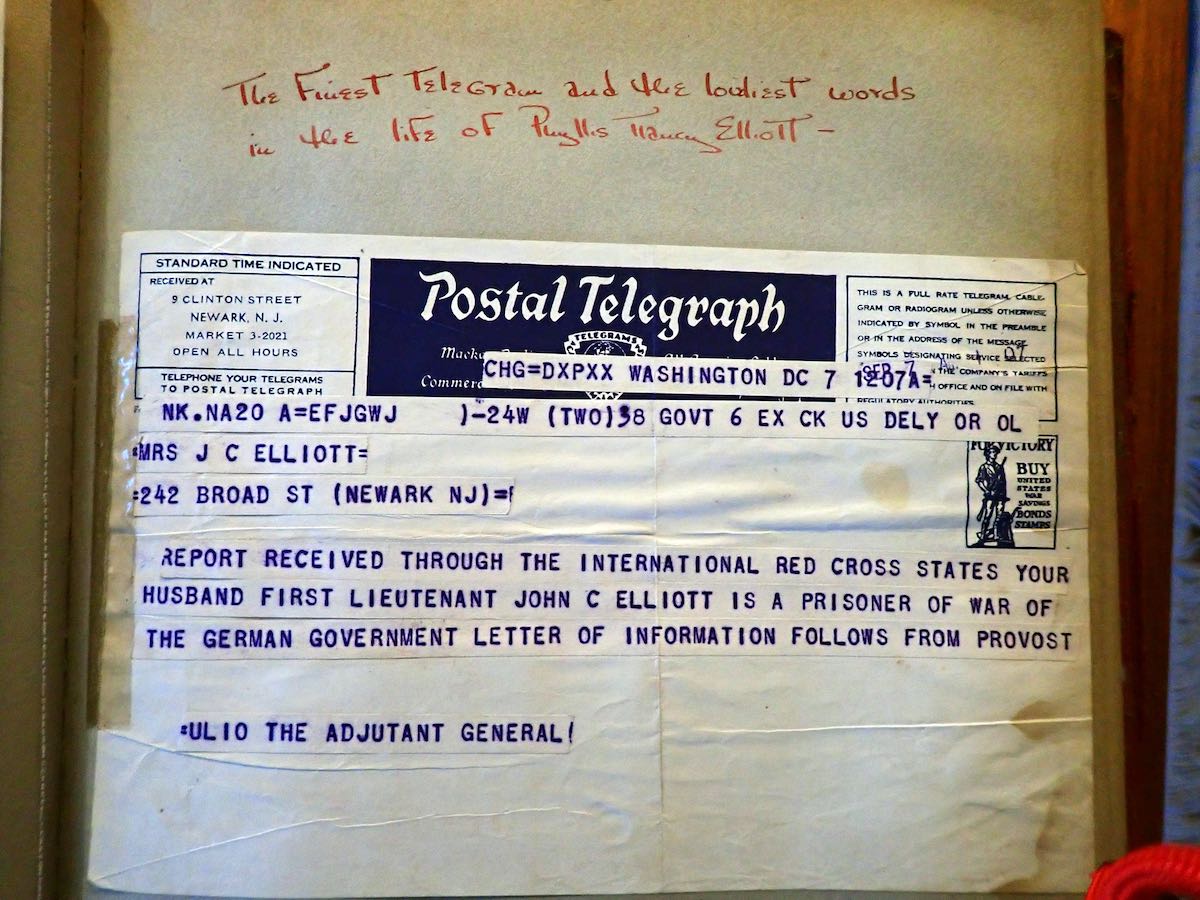

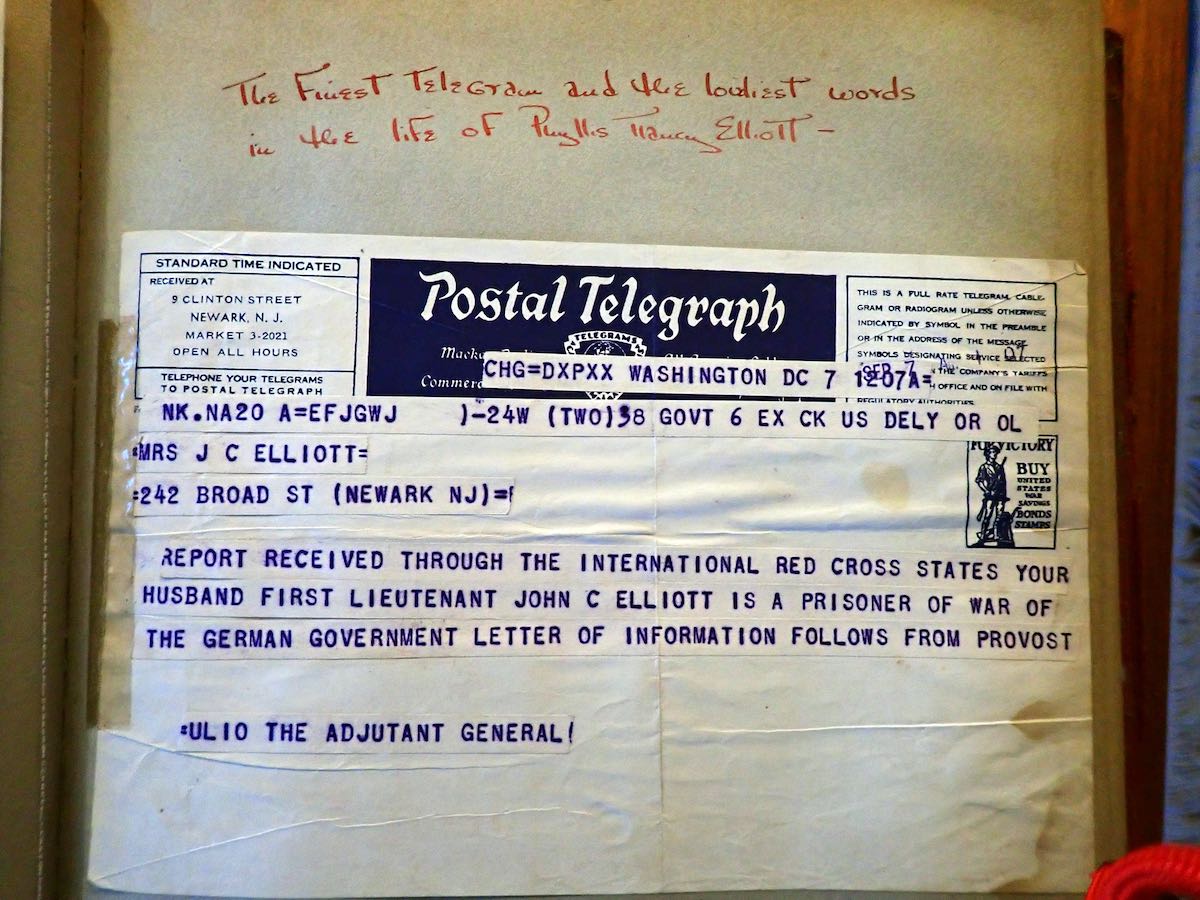

A telegram arrived:

Mrs. J C Elliott =

Report received through the International Red Cross states your husband First Lieutenant John C Elliott is a prisoner of war of the German Government . . .

Notation in the scrapbook above the telegram (in my Mother’s hand) reads:

The finest Telegram and the loudest words in the life of Phyllis Nancy Elliott

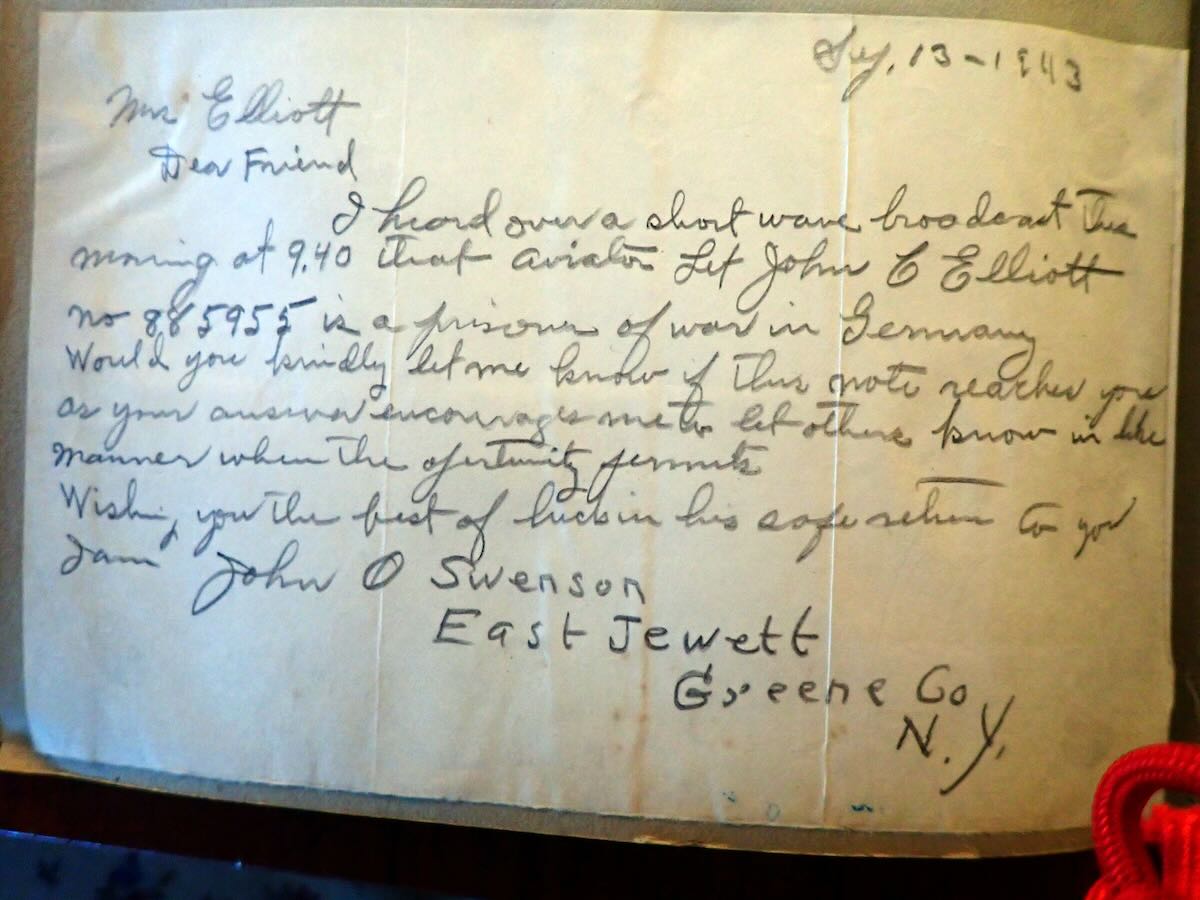

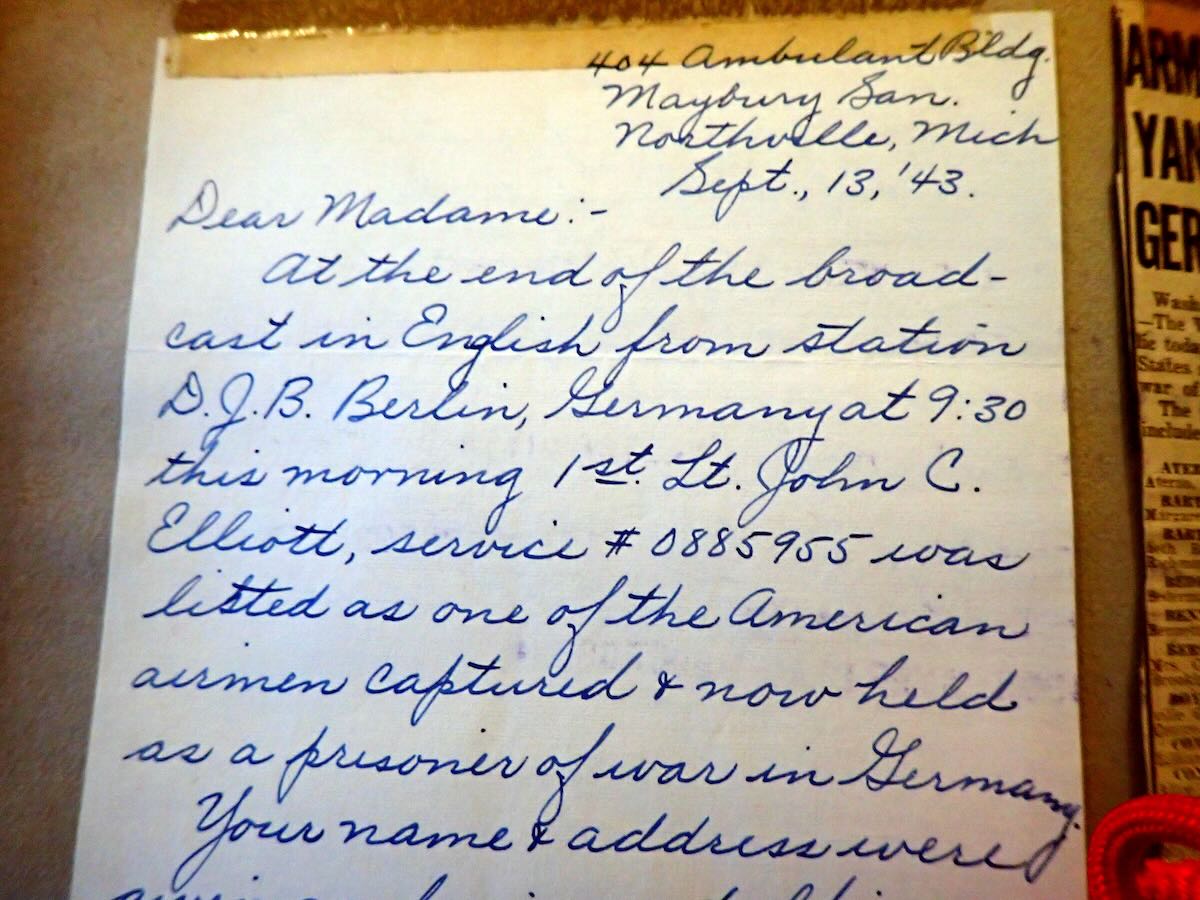

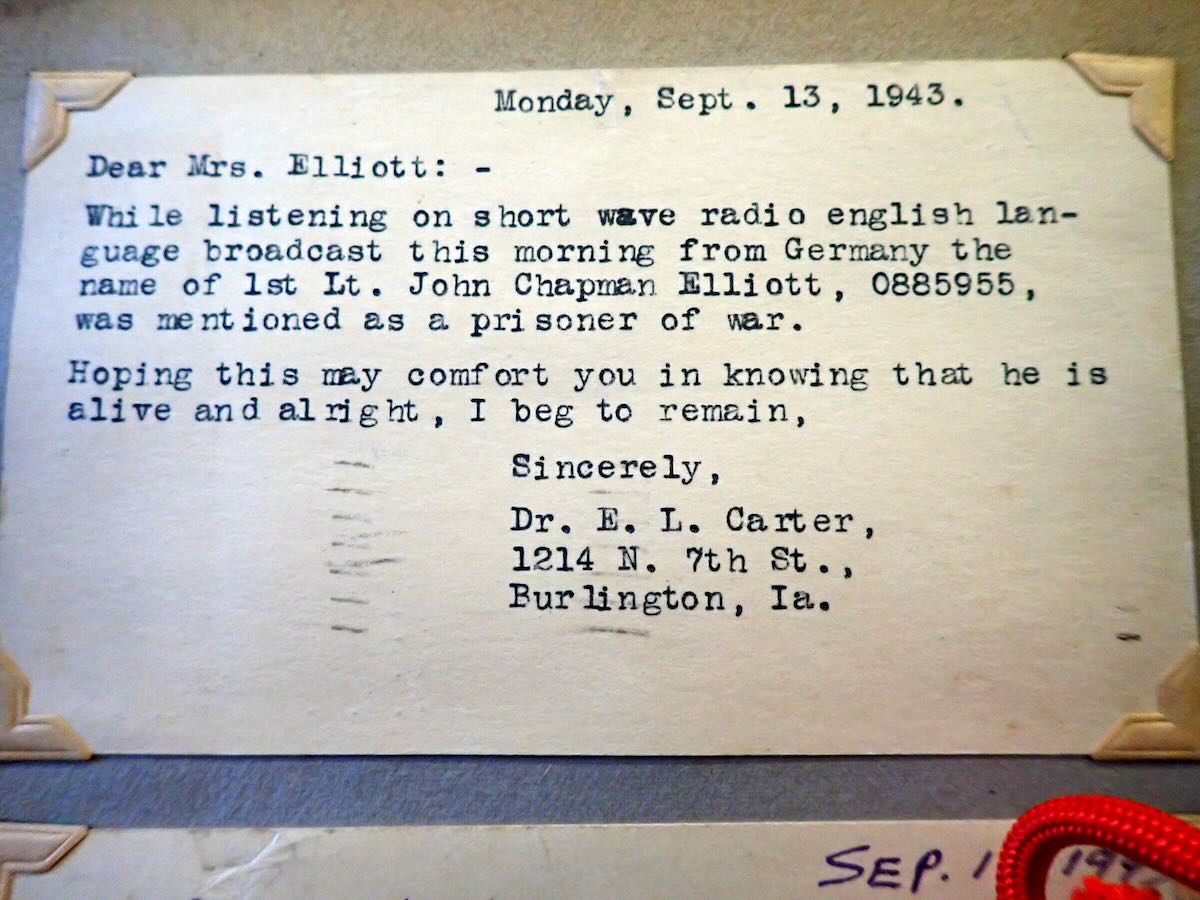

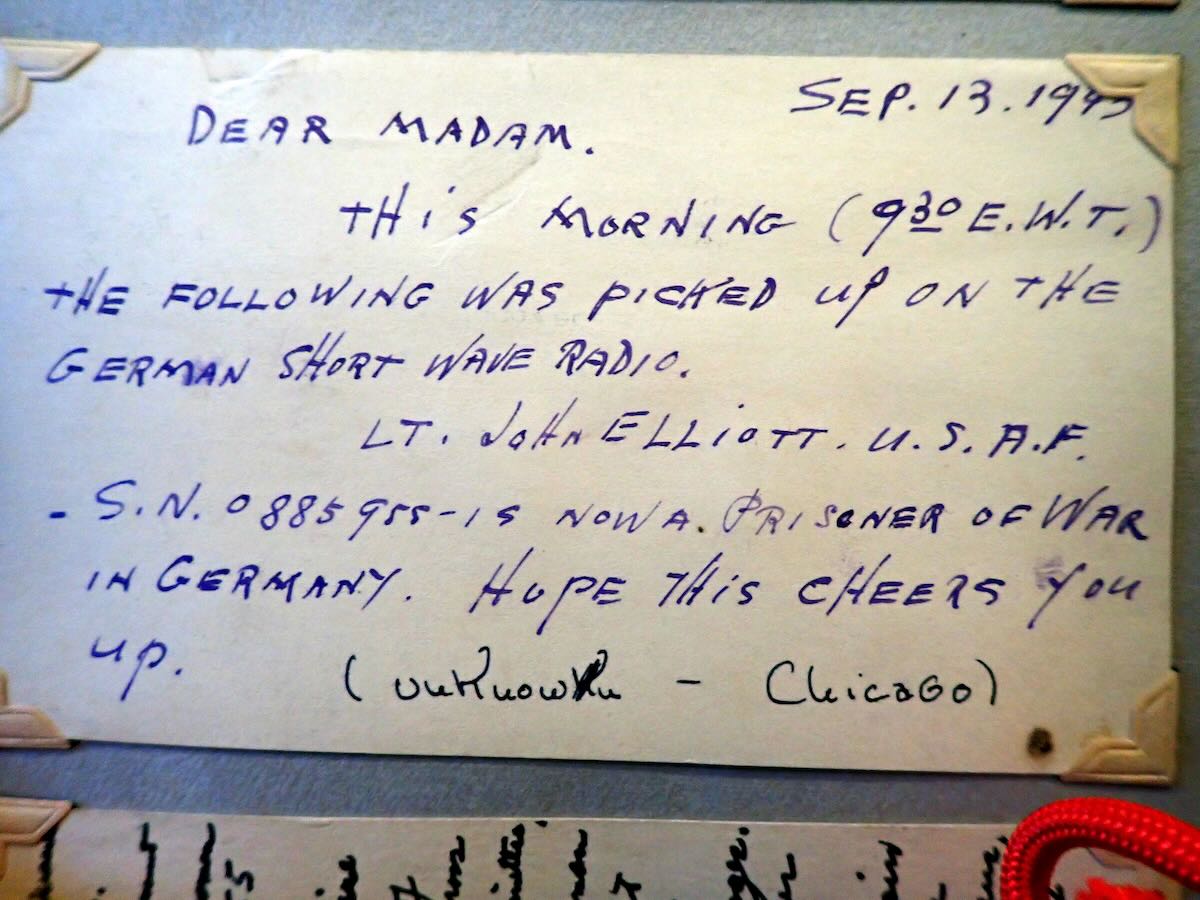

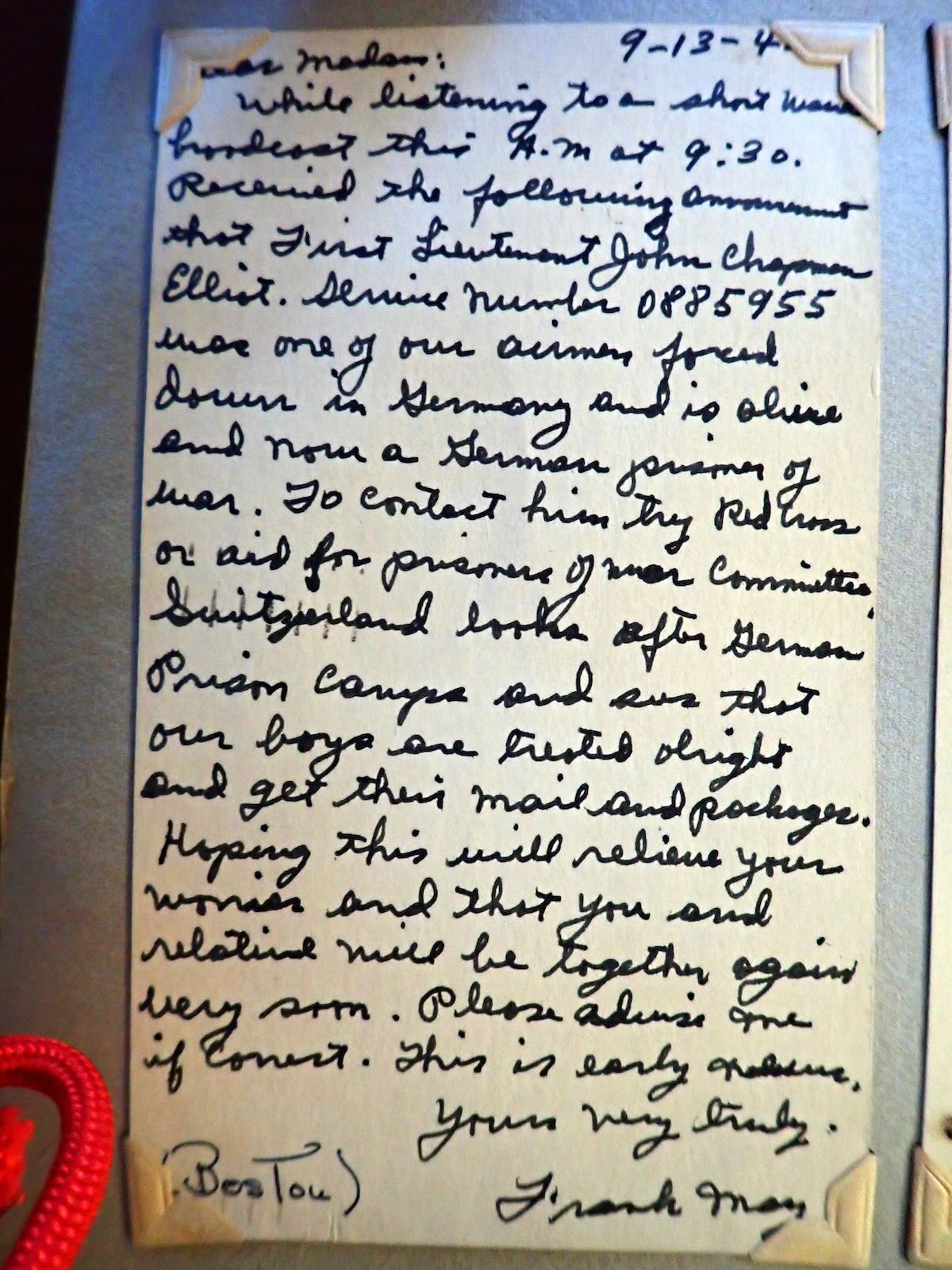

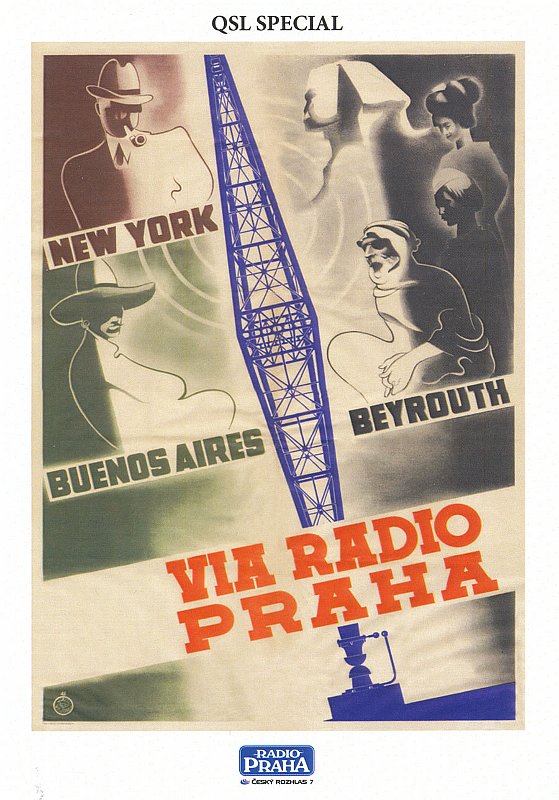

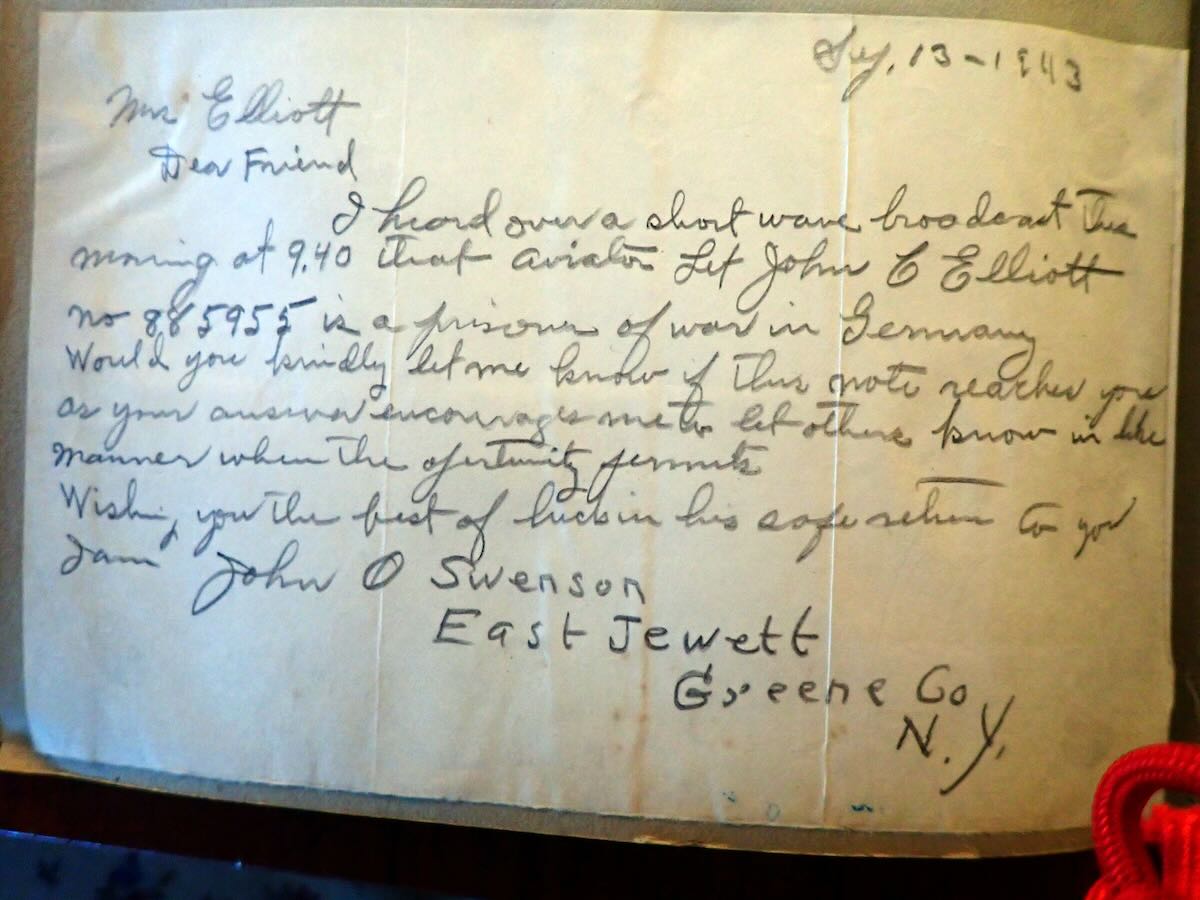

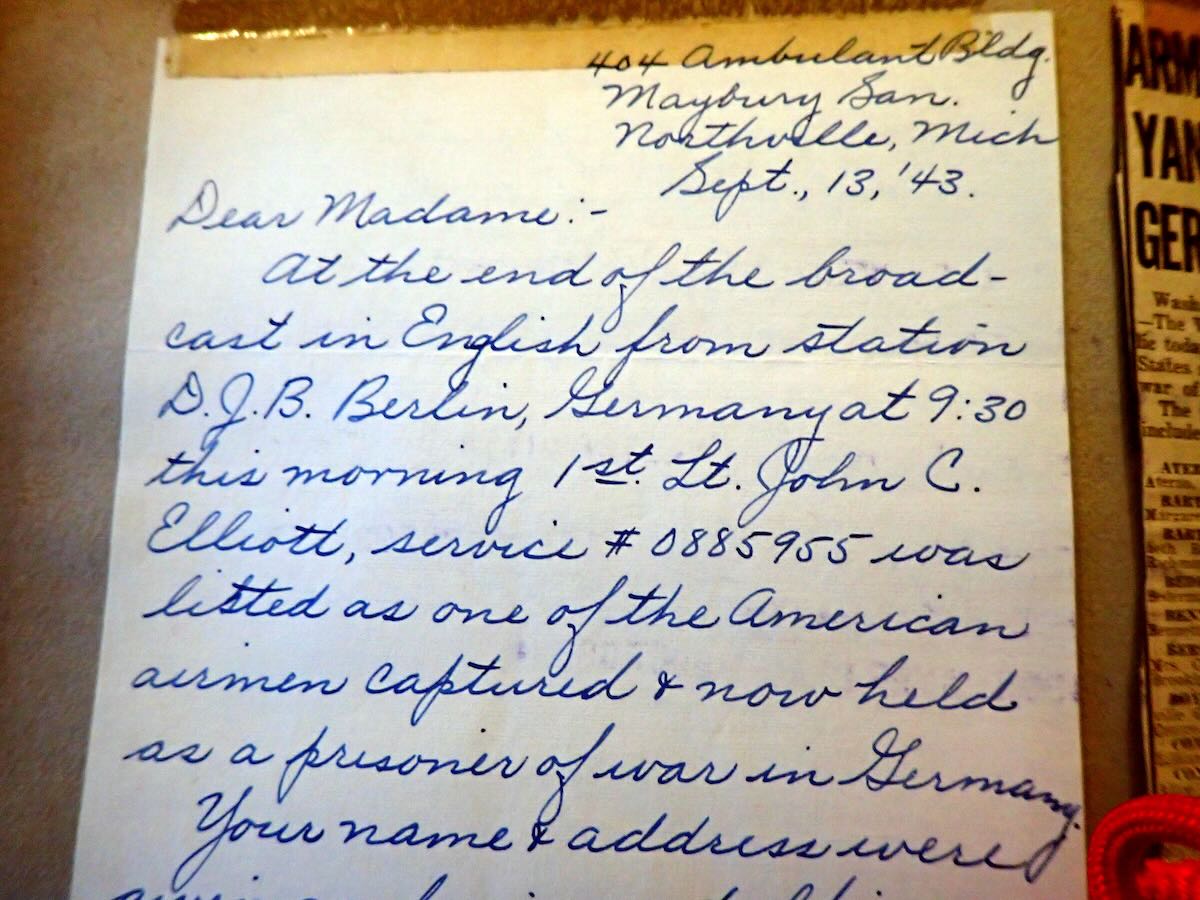

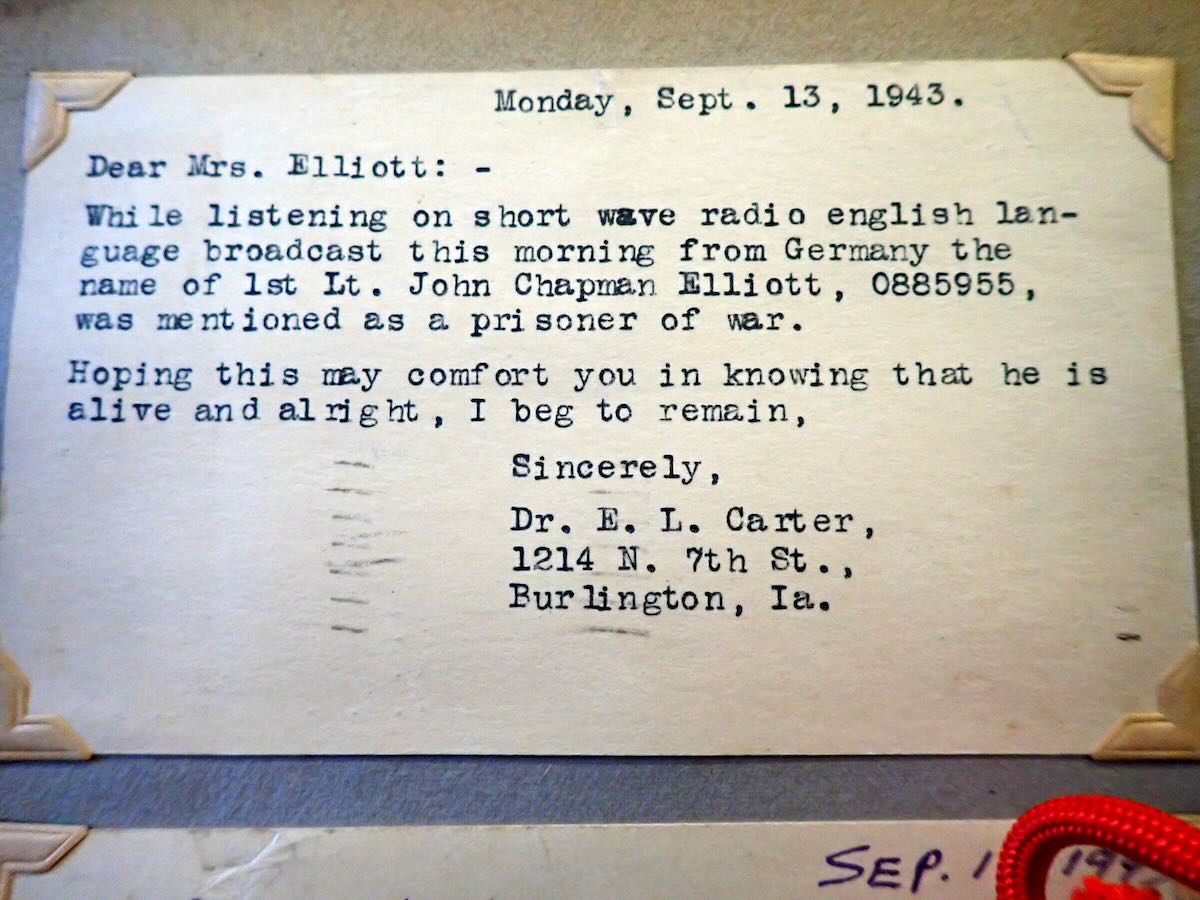

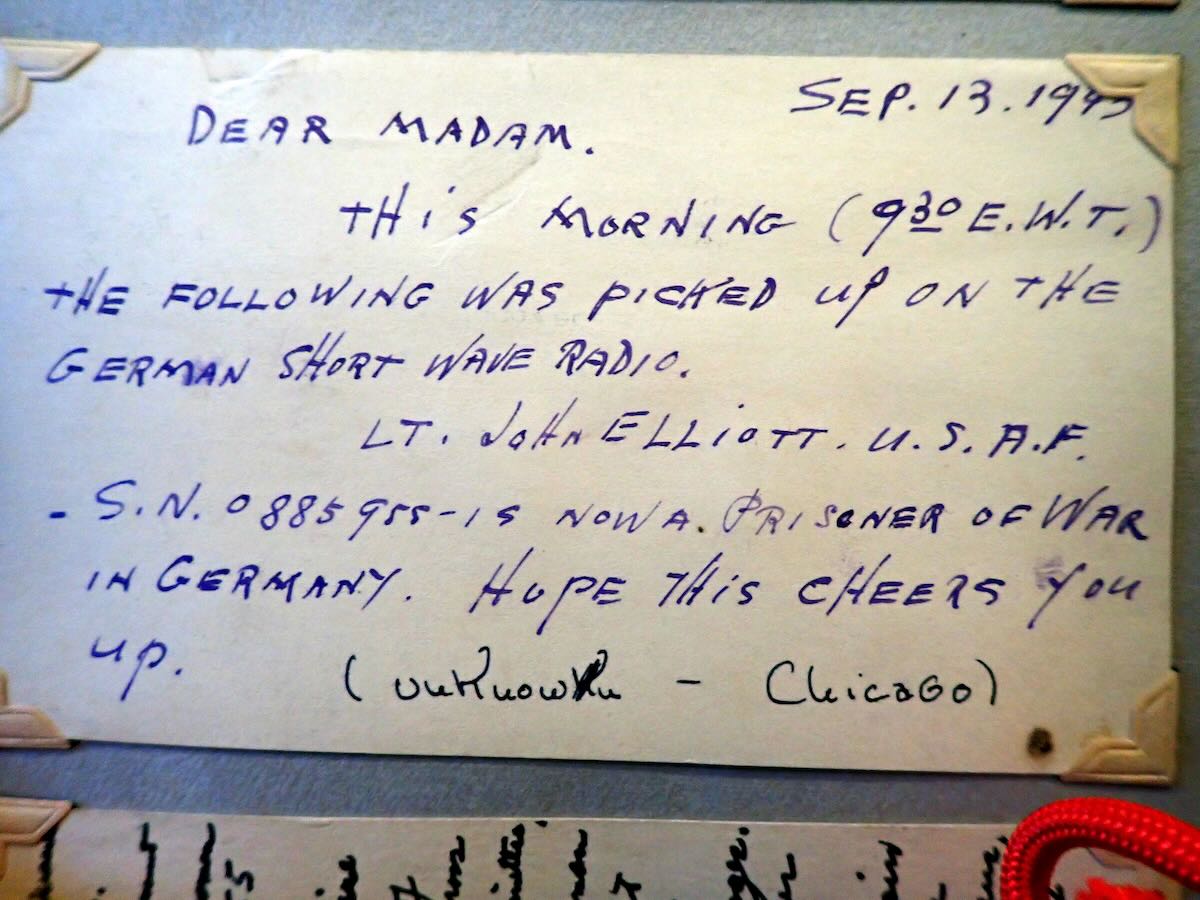

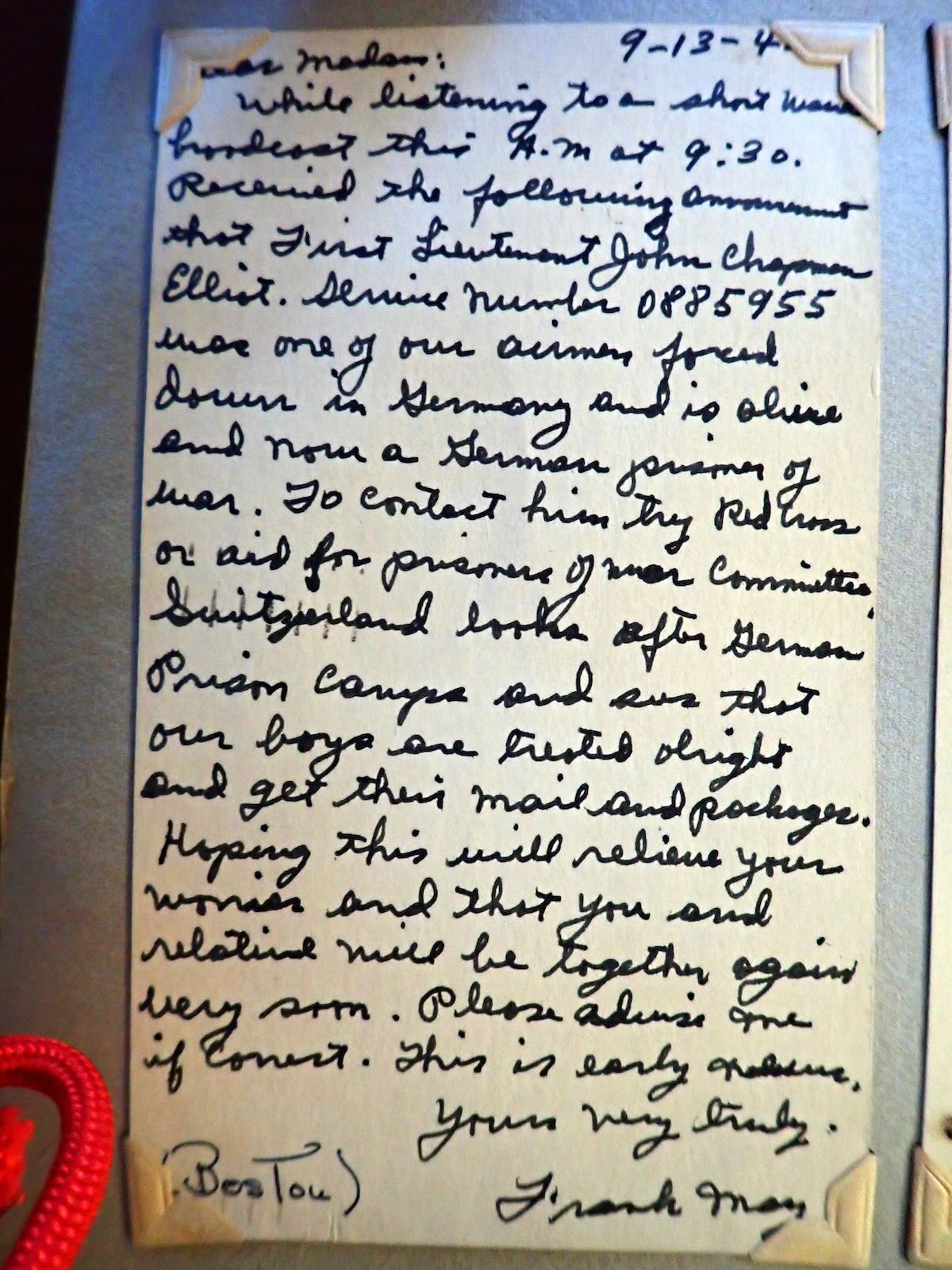

On or around the same time, postcards and letters arrived from around the country. From Northville, Michigan; Green County, New York; Grand Rapids Michigan; Auburn, Maine; Burlington, Iowa; Chicago, Illinois; Boston, Massachusetts, shortwave radio listeners wrote to Mrs. Elliott to tell her that they had heard – on a broadcast from Berlin, Germany – First Lieutenant John Elliott is a prisoner of war, and offering words of comfort or explanation:

Wishing you best of luck in his safe return to you,

I am a patient at the above sanatorium and as I have a quite powerful radio receiver I am taking this means of doing my bit for the boys in our armed services,

Hoping this may comfort you in knowing that he is alive and alright,

Hope this cheers you up.

Hope this will relieve your worries . . .

Words cherished and pasted into a scrapbook.

My Dad later told me what happened. Their Wellington bomber was badly shot up, and the pilot informed the crew that it was time to bail out.

My Dad cranked his tail turret around so that the door opened into the air. He flipped backward out of the aircraft. For a little while, one of his electrically-heated flying boots caught on the door frame. Hanging upside-down, he kicked the boot off, pulled the ripcord on his parachute, and landed with green stick fractures in both legs. He hobbled around Holland for three days while trying to avoid the Germans. He was captured and spent two and one-half years as prisoner of war.

Lower right: My Dad.

When the war ended, he was repatriated, and in 1946, your humble correspondent showed up. The photos are of actual postcards and letters in an 80-year-old scrapbook kept by my Mother and passed down to me.

And so, dear reader, never belittle your hobby of listening to the airwaves, because you never know when something you heard may be able to offer comfort in times of trouble. I know it certainly did for my Mother.

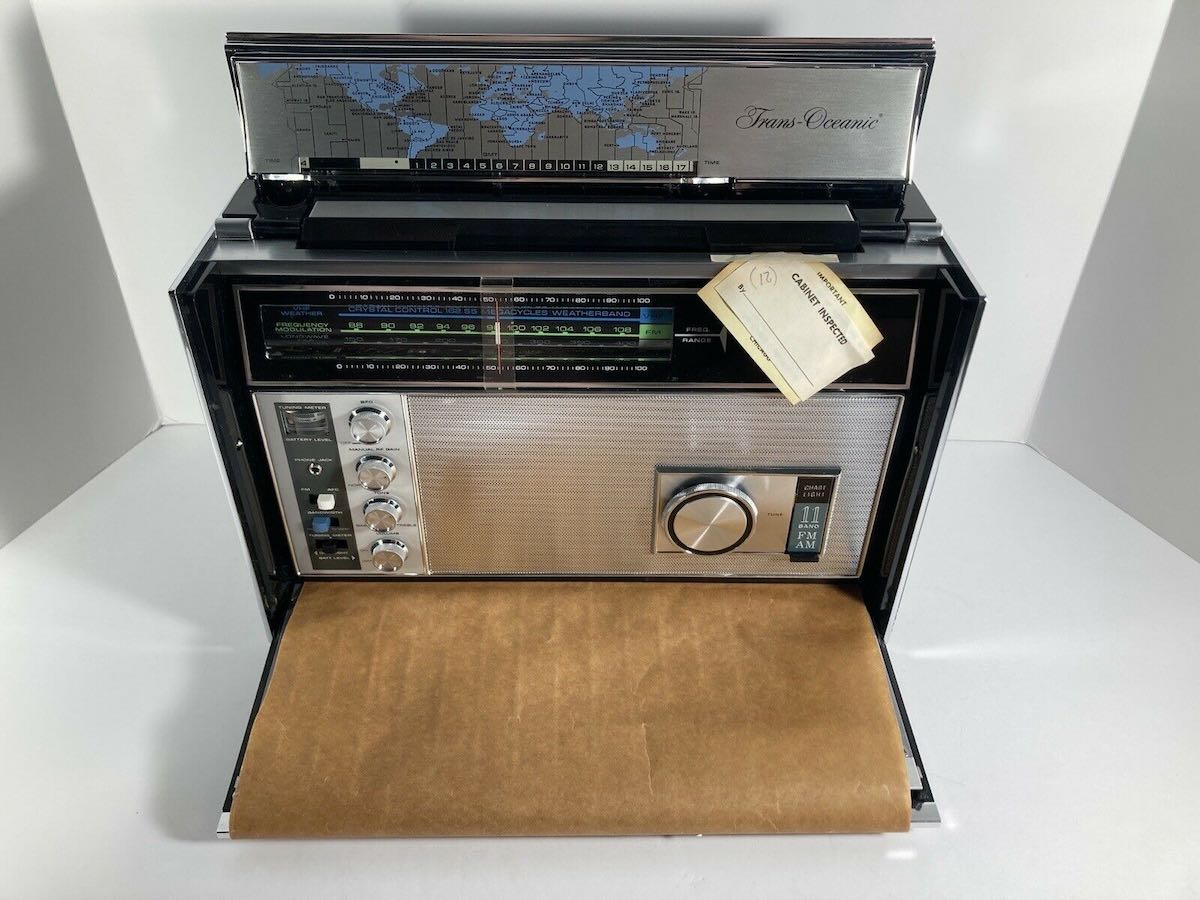

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Dan Robinson, who shares a link to this recent listing of an NIB (New In Box) Zenith Trans-Oceanic Royal 7000Y R-7000-1 that fetched $3.050 on eBay. Dan believes this may be a record price for this model.

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Dan Robinson, who shares a link to this recent listing of an NIB (New In Box) Zenith Trans-Oceanic Royal 7000Y R-7000-1 that fetched $3.050 on eBay. Dan believes this may be a record price for this model.