Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Don Moore–noted author, traveler, and DXer–for the latest installment of his Photo Album guest post series:

Don Moore’s Photo Album: Cuenca, Ecuador (Part 2)

by Don Moore

In the song Por Eso Te Quiero Cuenca (That’s Why I Love You Cuenca) the singer recites a litany of the many reasons to love this city. What do I love about Cuenca? Well, unlike the song, I won’t include well-roasted guinea pig.

The elevation of 2560 meters (8,400 feet) gives Cuenca a comfortable spring-like climate year-round. Daily highs are usually around 20C/70F. Nights are chilly but not cold. Most days have at least several hours of sun, even during the rainy season (as it is now). There are numerous green parks and plazas including long tree-lined walking paths along the two main rivers that run through the city. The drinking water, which comes from high up in the mountains, is the best in South America. Yes, you can drink it right from the tap.

A walking/bike path runs along the Yanuncay River for over six kilometers through the south side of Cuenca. A similar path runs along the larger Tomebamba River in the center of town.

The people of Cuenca are among the friendliest I’ve found anywhere. It’s a well-run, educated city with lots of civic pride. The metro area population is only about a half-million so it’s small enough to easily get anywhere but large enough to have the benefits of a city. Cuenca has several good universities and theaters and the symphony orchestra gives free concerts most Friday evenings. It’s a pleasure to simply stroll through the beautiful architecture in the old centro neighborhood.

Getting around Cuenca is easy. A ride on the excellent bus system costs just thirty cents and taxi rides usually run under two dollars. And, unlike the much larger cities of Quito and Guayaquil, Cuenca has a mass transit system. In 2013 city leaders voted to put in a light rail line. Doing so required digging up two of the main streets through the old downtown but rather than just dig up two streets they decided to dig up the entire old downtown … to replace the aging water and sewer systems, move all electric lines and cables underground, and install high-speed fiber optic Internet. (Fiber optic Internet was also run above ground in the newer neighborhoods outside the centro.) The result is one of the few places in Latin America where one can enjoy beautifully restored architecture and colonial churches without the views being marred by powerlines. And the Internet here is better than most places I’ve stayed at in the United States.

Those are just a handful of the reasons that I love Cuenca.

Early Radio in Cuenca

Radio broadcasting in Ecuador started in 1925 with Radio El Prado in Riobamba, a small city in the center of the country. Other stations soon started up in Guayaquil and Quito, including HCJB in 1931. Broadcasting came to Cuenca in 1934 when a group of friends purchased a homemade ten-watt transmitter from an engineer in Guayaquil and put it on the air as La Voz de Tomebamba. The name came from the main river flowing through Cuenca. At the time there were only four receivers in the city so the audience was rather sparse. La Voz de Tomebamba initially broadcast for only one or two hours a night and most of the musical selections were done live as there weren’t many 78 RPM records in town. Years later one early listener reminisced, “It was sixty percent noise. Only radio fanatics could be entertained by listening to such a thing.”

Gradually, the owners added new equipment and expanded the daily schedule. A fifty-watt transmitter was added in 1938 and by 1947 the power had been increased to two hundred watts. The first frequency listing that I’ve found for La Voz de Tomebamba was for 4200 kHz in a 1944 FBIS newsletter. The 1947 WRTH listed it as on the air from 0000 to 0430 GMT on 4200 kHz. And that was the station’s only frequency. Until the 1960s it was very common for radio stations in Ecuador to only broadcast on shortwave and not on medium wave. For example, the 1957 WRTH lists eighty Ecuadorian stations on shortwave (not counting HCJB) but only fifty-nine on medium wave.

Sometime in the early 1960s La Voz de Tomebamba made the switch to medium wave and left shortwave. Their 4200 kHz frequency is not listed in the 1965 WRTH, nor are they listed in any later ones. (I would be interested to hear from anyone who remembers listening to them on shortwave.) The changes may have had to do with financial problems the station was having. It closed in 1967 and remained off the air until returning under new ownership four years later. Today La Voz de Tomebamba is one of the most popular radio stations in town and has an excellent news department. Their sister station, Super Rock FM 94.9, is very popular with younger listeners.

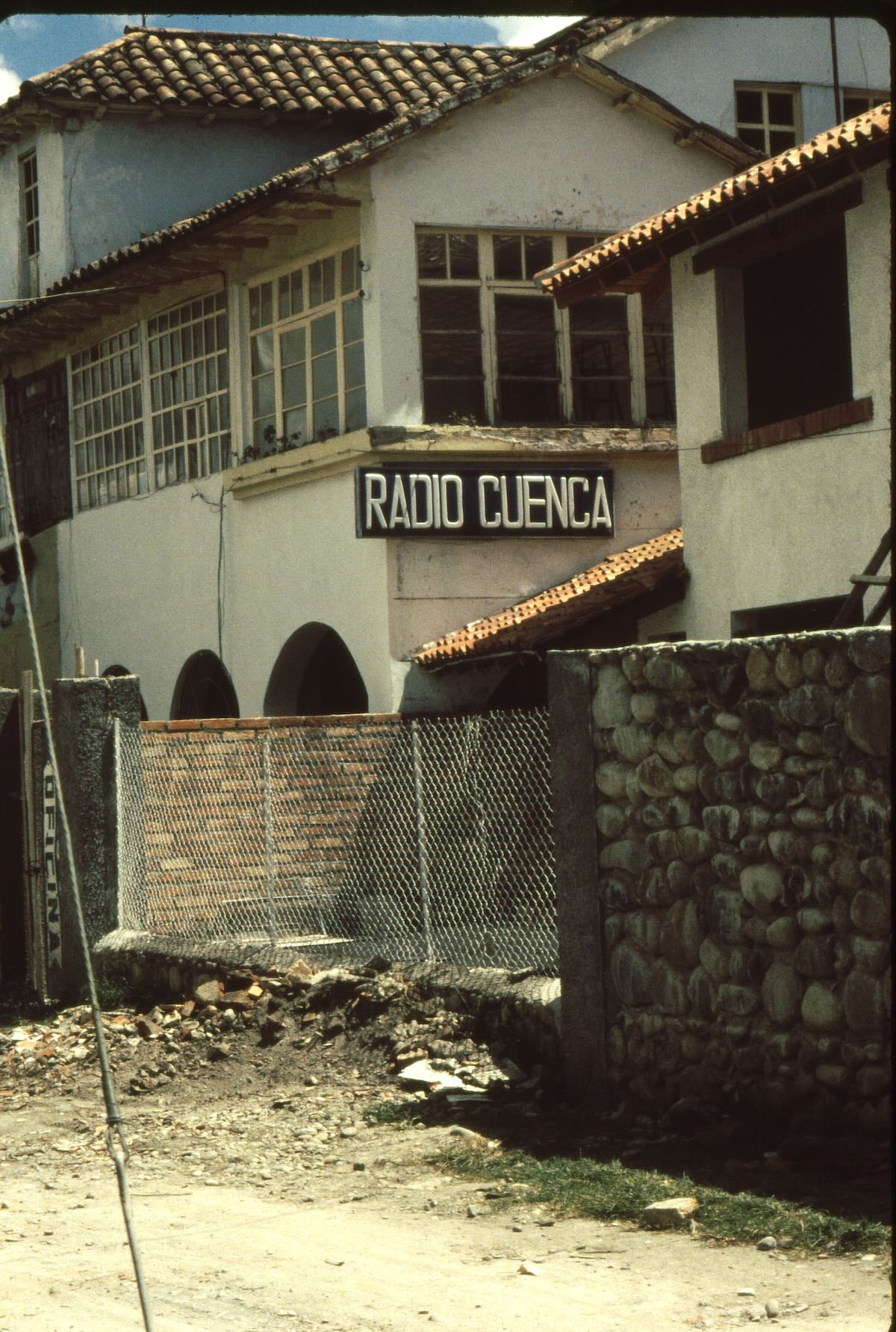

The second station in Cuenca was Radio Cuenca, which began broadcasting in October 1945 on 2830 kHz with two-hundred watts. It was included in a 1953 list of stations logged by the Universal Radio DX Club of Indiana. To the local audience, Radio Cuenca was best known for its many live music broadcasts.

In the 1960s the Ecuadorian government began to better manage the radio dial and moved stations to standard frequencies. Radio Cuenca is listed on 5950 kHz in the 1971 World Radio TV Handbook and was sporadically active in the 1970s. I never managed to hear them but did visit the station in 1985 to pick up verifications for a few friends.

Recording:

Radio Cuenca 1976 via On The Shortwaves

Ahead of My Time

In the first part of this series I wrote that I clearly remember sitting in a park one day in 1997 and commenting that Cuenca would be a perfect place to retire in someday. I added that I was only ten years ahead of my time. Just what did I mean by that? I discovered in 1985 and again in 1997 that Cuenca is one of the best places in Latin America to visit or live in. But the rest of the world didn’t know that … yet.

In the early 2000s a few foreign retirees began to trickle into Cuenca. By 2007 there may have been a few dozen. Then in 2008 International Living magazine in the USA and Stern magazine in Germany named Cuenca the top destination for expatriate retirees. That same year other publications such as National Geographic and Lonely Planet began lauding Cuenca’s charms as a travel destination. Even so, it may have taken years for many retirees to find their way to Cuenca. But later that year the world’s economy went into meltdown and many adventurous retirees began looking for a place where their diminished retirement incomes would go further than at home. Within a year over a thousand foreign retirees had settled in Cuenca. A few years later it was over ten thousand.

Since then the numbers have stabilized at around ten thousand as people come and go. Some spend a few years and then head home, usually because they miss family. Others become accustomed to expat life and after a few years move elsewhere in Ecuador or to another country. Still, it’s not hard to meet retirees who have been here ten or fifteen years. Americans are by far the largest group but there is also a significant number of Canadians and more than a few Germans.

Why do people like it here? Certainly for all the reasons I mentioned earlier. Also, Cuenca is very affordable; it’s easy to live here on $1000 a month. Nice fully furnished one-bedroom apartments with all utilities including high-speed Internet start at around $400 a month. Fresh fruits and vegetables are abundant and cheap. Most retirees find their health improves after moving to Cuenca. And health care is excellent and inexpensive (by American standards).

Fruit stand at the Diez de Agosto market. Five dollars can buy enough fruit and vegetables for a week.

Finally, it’s hard to be bored or alone here. There are frequent Ecuadorian cultural events, such as the free symphony, plus lots of opportunities to mix with fellow gringos. One night I may go to see an Ecuadorian folk music show and then the next day head to a gringo bar to watch an NFL football game and have a beer and a burger. I have a better social life when visiting Cuenca than I do at home. Most gringos say the same.

One thing that makes this all possible is that Cuenca is a forward-thinking, welcoming, and progressive city. But it wasn’t always that way, as the story of one Cuenca radio station illustrates.

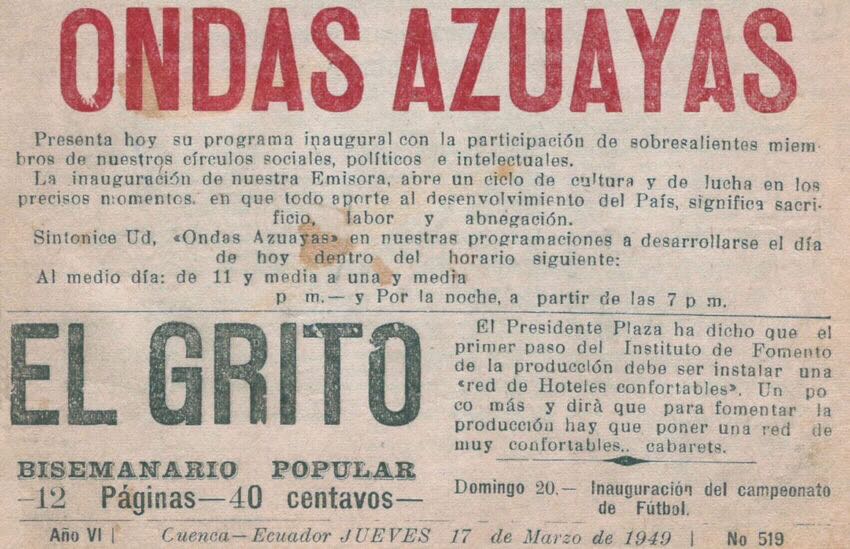

Ondas Azuayas

Like many early radio stations, Ondas Azuayas started as someone’s hobby. In the mid-1940s Fritz Kramer, a German resident of Cuenca, bought a two-hundred-watt transmitter and began experimenting with broadcasting. After Fritz died in 1948 his family leased the transmitter to José and Alberto Cardoso, two brothers who had previously worked at La Voz de Tomebamba and Radio Cuenca. After playing around with broadcasting for a few months the brothers decided to go into radio full time. Ondas Azuayas was officially launched in 1949 on 4980 kHz shortwave. The name (Azuayan Waves) comes from Azuay, the province Cuenca is capital of.

In some ways Ondas Azuayas was just another commercial broadcaster with music and drama programs. But one important element separated it from the competition: an emphasis on good journalism from the start. To the Cardoso brothers, radio wasn’t just a way to make money but also a way to improve Ecuadorian society and government. That meant standing up to the three parties that controlled the country: wealthy families, the military, and the Catholic Church. The risks were many but Ondas Azuayas never shied away from exposing corruption, self-serving policies, and misdeeds by those running their community and their country. Ondas Azuayas actively supported labor unions, groups fighting for peasant rights, and anyone sincerely working to fix Ecuador’s broken democracy. In response, the defenders of the status quo whose interests were being accused Ondas Azuayas of being a front for Communism. (Years later it came out that the CIA had investigated the Cardoso brothers.)

Ondas Azuayas’ fearlessness led to it being nicknamed la emisora combativa, or the fighting radio station. And fight it did. During the 1950s and 1960s the station was closed several times and José Cardoso was jailed twice. The most serious closure was in 1961 when elected President José Maria Velasco Ibarra declared himself dictator and then began to implement heavy-handed policies. When labor unions called for a general strike Ondas Azuayas openly publicized and supported it. A few days later, on November 2, a force of about one-hundred soldiers surrounded the station and used tear gas and the threat of machine guns to force everyone to leave. The soldiers then ransacked the station and destroyed most of the equipment. But other powers in Ecuador, as well as in Washington D.C., realized that Velasco Ibarra’s extreme policies had become a threat to stability. On November 7 the military removed him from office and put the Vice-President in charge. A few days later Ondas Azuayas was back on the air with borrowed equipment.

Ondas Azuayas especially took aim at the Catholic Church for its oversized influence on the government and society. The Archbishop of Cuenca referred to it as a “venal station” and called on listeners to boycott it. On numerous occasions conservative priests encouraged parishioners to gather and protest in front of the Ondas Azuayas’ office and studio complex. Several times the crowds got out of control and threw stones at the building and at least one time a gunshot was fired. Once a priest planted explosives in his own pulpit and then tried to blame it on “radicals” listening to Ondas Azuayas.

The Catholic Church in those days was closely aligned with the powerful forces that controlled the economy and society. In the anti-communist paranoia of the 1950s and 1960s, anyone who spoke up for any kind of reform was automatically labeled a comunista. But by the mid-60s many leaders in the Church began to understand that the real threat wasn’t Communism but rather a brutal economic system that could make Communism the only hope for change. In many places, including Ecuador, the church began working with forces for change, such as Ondas Azuayas.

World Radio Handbooks and other listings from the 1950s and 1960s list Ondas Azuayas on 4980 kHz shortwave. In the 1960s they added medium wave on 1265 kHz but later changed to 1100 kHz and then to 1110 kHz. According to the WRTH, Ondas Azuayas used 250 watts on 4980 kHz in the 1970s and then raised it to 10 kilowatts around 1979. Regardless of the power, the station was always difficult DX in my experience. The problem was that they were on the same frequency as Ecos del Torbes in Venezuela. In North America Ondas Azuayas could only be heard on rare occasions when either Ecos del Torbes was off the air or Ondas Azuayas stayed on late, after the Venezuelan had signed off. My only loggings were twice in 1979 in Pennsylvania and then again in 1985 when I was in Ecuador. Fortunately the station was a good verifier and many DXers, including me, received a QSL card and pennant.

Recording:

Ondas Azuayas as heard in Pennsylvania in October 1979.

I visited Ondas Azuayas twice, first in 1985 and again in 1997 and each time received a tour from José Cardoso’s son, who was then in charge of the station. The focus was always on showing me the newsroom, which was the heart of the station. Ondas Azuayas’ days of being a David daring to attack the Goliaths running Ecuador were gone. Now one of the most respected news sources in Ecuador, it had close working relationships with other broadcasters around the world, including Radio Nederland and Radio France.

Broadcasting was changing and organizations around the world becoming more interconnected. In 1995 Ondas Azuayas and Radio Quito teamed up for the first satellite relays in Ecuador. Then in 1997 Ondas Azuayas turned in its shortwave license and became one of the first radio stations in the world to begin broadcasting online using RealAudio. DXers may question that decision but most people are not DXers. With online streaming Ondas Azuayas could better reach Ecuadorians around the world than they ever could have with their puny shortwave transmitter.

Troubles in Paradise?

The story of Ondas Azuayas is closely tied to the struggle between poor people without power and a small group of privileged people who looked down on them and took advantage of them. So what about the relationship today between the foreign retirees in Cuenca and the local people? Retirees, even those living on a thousand-dollar-a-month pension, are far better off than the average cuencano. And few retirees know much Spanish or have experience living in foreign cultures when they arrive. There’s a clear potential for big problems.

There are places in Latin America where the ‘Ugly American’ syndrome is alive and well. To be fair, it’s really about self-centered privileged people from wealthy countries in general. (I could name a few countries that seem to produce even worse ‘bad apples’ than mine does.) But my countrymen are more numerous and therefore more visible.

A few years ago I visited a small town in Panama that was home to about two-thousand foreign retirees. With few exceptions, the foreigners lived in expensive gated communities in the mountains overlooking the town and had no contact with the local people aside from their hired servants and gardeners. Out of curiosity I visited a real estate office catering to the foreign community. Most of the homes were priced at over one million dollars. None was under half-a-million. Those prices buy a lot of luxury in rural Panama. And that lifestyle creates an immense gulf between the foreign community and the local people.

When I returned to Cuenca for a week in 2015 for the first time in eighteen years I had no idea what to expect but I knew it might not be good. If so, I would not be returning. What did I find? Well, since 2015 I’ve made three more visits staying for about two months each time. I can’t say that problems don’t exist but the relationship between the local community and the foreign retirees is far better than anything I expected.

The retirees who come to Cuenca are not the kind of people who would isolate themselves in a luxurious mountainside home. There probably are a few wealthy expats here who live in million-dollar houses. But most expats live in apartments in the city and the rest in modest homes in the outer neighborhoods and nearby towns. And the expats don’t just stick to themselves. Some neighborhoods do have higher concentrations of gringos than others, but retirees can be found living all over Cuenca as well as in the surrounding towns.

My Spanish is better than 99.9% of the expats I meet here. But everyone I meet knows some Spanish and understands the importance of learning the language and culture. Spanish classes are very popular. And most retirees have Ecuadorian friends. A few weeks ago I spoke with an eighty-year-old American who proudly told me that she was the only non-Ecuadorian in her ten-unit building and that she was friends with all her neighbors.

Finally, the foreign residents here give back to the local community. Expat-sponsored organizations include a shelter for battered women, a soup kitchen, a food pantry, and services for single mothers. Some retirees volunteer in schools. Three years ago a group raised thirty-thousand-dollars to import medical equipment for the severely handicapped child of a waiter at a local restaurant.

And that is one more thing I love about Cuenca. The expat community are good people.

More Cuenca Radio

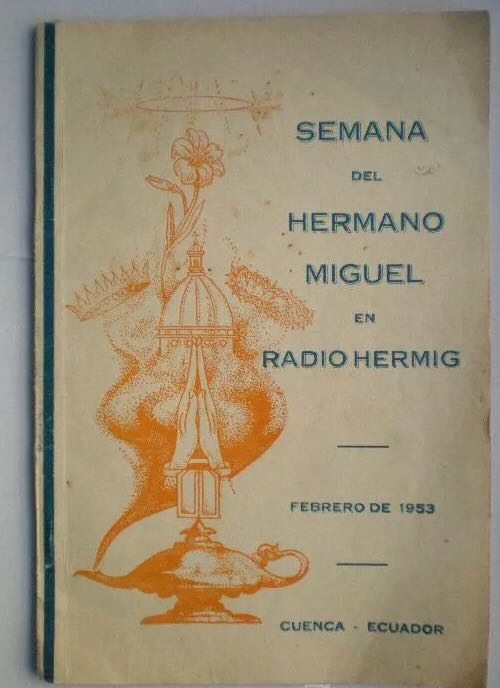

Cuenca has been home to other shortwave stations over the years. World Radio Handbooks from the late 1940s list Radio Alborada and ones from the 1950s list Radio Hermig and Radio Nuevo Austral. Radio El Mercurio, owned by the newspaper of the same name, used 6070 kHz in the 1960s and 1970s. I never logged it and so never visited it. The station still broadcasts on medium wave.

Another Cuenca broadcaster from the 1950s was Ondas Azules, the station where Doña Manena of Radio Popular Independiente got her start. For the first several years the station only broadcast on shortwave using a reconditioned transmitter purchased from Braniff International Airways. In the late 1960s the name was changed to the intentionally misspelled Radio Splendit. Years later the name was corrected to Radio Splendid. Their shortwave signal on 5025 kHz was not an easy catch; I logged them just once in 1979. I visited them in 1985 and again in 1997.

Recording:

Radio Splendit 1976 via On The Shortwaves

In the early days of broadcasting from Cuenca, shortwave was the band of choice. Later medium wave became more important but shortwave continued to have a role. Then FM arrived in the 1970s and gradually shortwave became an unnecessary remnant of days-gone-by. The last shortwave broadcast in Cuenca was about twenty years ago from La Voz del Río Tarqui. Today it’s FM that rules and AM is gradually dying. After over 72 years on the air, Ondas Azuayas signed-off for the final time on June 7, 2020. A month later, on July 10, Radio Splendid left the airwaves. Both were the victims of advertising revenue switching to FM and to online platforms. The owners continue to operate FM music stations, but two important voices in Cuenca’s radio history are gone forever. For Cuenca’s shortwave stations, all that’s left is the memories of listening to them. And those memories are one more thing that I love about Cuenca.

* Thank you to Jerry Berg for his help with the historical information.

Links

- La Voz de Tomebamba: https://www.lavozdeltomebamba.com/

- Song Por Eso Te Quiero Cuenca: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pefg3YwjBR4

- My Cuenca Resources: http://www.donmooredxer.com/trip/cuenca.html

In my video folder I’ve added recordings from 1997 of La Voz de Tomebamba, Radio Splendit, and Ondas Azuayas. In the Ondas Azuayas video there is a greeting to DXers at 2:00 minutes. In the La Voz de Tomebamba video an ID is given at 02:15. The videos are in MKV format and can be viewed with the free VLC Player, among other applications.

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1cuTpMOBN9-HzwBrjOMrmg1l-SJnqtp8o?usp=sharing

Great stuff, Senor Donald!