Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Don Moore–noted author, traveler, and DXer–for the latest installment of his Photo Album guest post series:

Don Moore’s Photo Album: Albania – Part One

Finding Radio Tirana

More of Don’s traveling DX stories can be found in his book Tales of a Vagabond DXer [SWLing Post affiliate link]. Don visited Albania in March 2024.

Of all the places that I’ve been to but wouldn’t have imagined visiting forty years ago, Albania is definitely at the top of the list. Yet here I am wandering around in Tirana’s coolest and most trendy neighborhood. I walk by an Argentine steak house, several Italian trattorias, a Texas cowboy-themed hamburger restaurant, and several sports bars with huge TVs tuned to football games (or soccer if you prefer). Boutique hotels, fashionable clothing stores, and shiny office buildings complete the scene. It’s just another upscale neighborhood in the global village. And it’s in Albania.

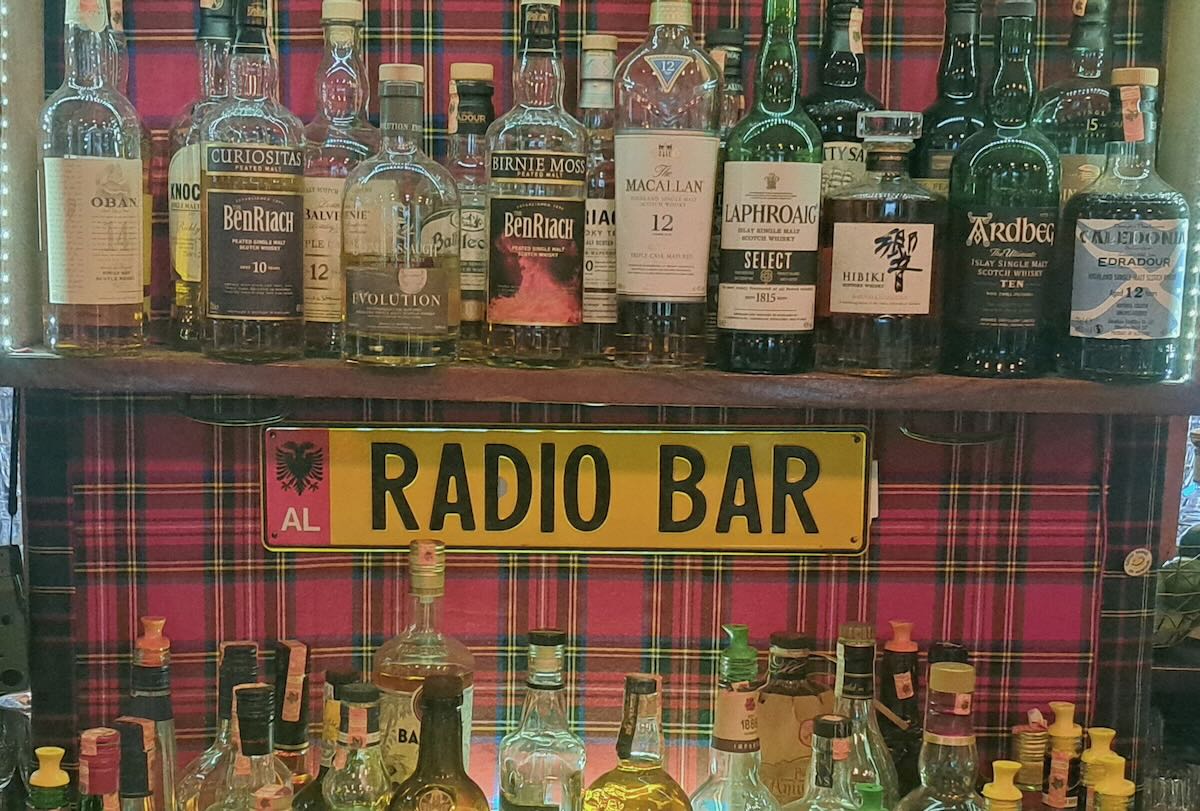

I hadn’t planned on getting an afternoon drink until the Radio Bar Tirana popped up on Google Maps. How could I not stop by a place with a name like that? The shelves behind the bar are filled with bottles of imported gin, whisky, tequila, and cognac, but I order a glass of raki, Albania’s version of the cheap firewater that every culture seems to have. It’s strong and burns my throat. No wonder Albanians have survived all that they have been through over the past six centuries. You have to be tough and resilient to drink this stuff. Or maybe it’s drinking raki that made Albanians tough and resilient.

The bar is staffed by two hipsters. I tell them about how decades ago (long before they were born) I used to listen to Radio Tirana on shortwave in the United States. They had never heard of Radio Tirana’s shortwave broadcasts and were amazed to know it was heard in the United States. I think they were also amazed that someone from outside Albania would have wanted to listen to the station during those terrible times. The bar, they explain, has nothing to do with any radio station but takes its name from the many old radios that line the walls. And it’s clear that I fit in better with the dusty wall décor than with the young bartenders or the chic patrons.

The back of the bar opens onto a large, covered patio filled with Albania’s version of smartly dressed young professionals. Late afternoon is the time to drink and to network. But the day is warm and sunny and no one wants to be inside. The main room is empty except for the bartenders and a man in the corner trying to work on his laptop despite the loud voices coming from the patio. I have the inside to myself so I wander around sipping raki, taking pictures of old radios, and remembering Radio Tirana.

The Kantata M model radio was produced in Murom, Russia by the Murom RIP Works in the 1970s.

Rodina-52M receiver made in 1952 by the Voronezh Elektrosignal Radio company in Voronezh, Russia. Thank you to Anatoly Klepov and Wojtek Zaremba for their assistance in identifying these two Soviet-era receivers.

The Red Lantern Model 269 was made in Shanghai in the 1960s. It predates the General Electric Super Radio by at least fifteen years so the “2 Band Super” name was not a takeoff on the popular GE receiver.

History in a Nutshell

Yesterday, I had visited the vast National History Museum on Skanderbeg Square in the heart of Tirana. All the peoples of the Balkans had a golden age and for Albanians it was the mid-1400s. The Ottoman Empire was the strongest and most aggressive power in the region but George Skanderbeg and his successors held off the Turks for fifty years. The Turks eventually conquered Albania and much of the Balkans but the delay likely prevented them from taking even more of Europe including Italy.

The Ottomans would rule Albania for over four centuries and in that time most Albanians converted to Islam. It was the only Ottoman territory in Europe where that happened. But Albanians continued to remember Skanderbeg, the Catholic who had led the fight against the Muslim Turks, as their national hero. And they never took their Islam as seriously as most other places. That’s why they still drink alcoholic raki.

Over the centuries, the Albanians would periodically raise the double-headed eagle flag of Skanderbeg and rebel against Ottoman rule. And each time the rebellion would be brutally put down. But by the early 20th century the Ottoman Empire had been significantly weakened and Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria had already won their freedom. In 1912 those countries went to war against the Ottomans to gain more land for themselves and as a side result Albania gained its independence. Then two years later World War I came and Albania and its neighbors were overrun by the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

When a war is over the victors usually divide the spoils and World War I was no different. Secret negotiations among the European powers included a plan to divide Albania between the new nation of Yugoslavia, Greece, and Italy. When the plans leaked out Albanians once again raised the double-headed eagle flag in defiance and this time received support from the United States. The Woodrow Wilson administration made sure that Albania would continue to exist with its pre-war borders intact.

Still, Albania’s bigger neighbors, especially Benito Mussolini’s Italy, continued to intervene in the country’s affairs. In 1928, at Mussolini’s urging, Prime Minister Ahmed Zogi declared Albania a monarchy and crowned himself as King Zog I. As the years passed King Zog came to realize that Mussolini’s plans for Albania were not friendly and he gradually distanced his government from the Italian ruler. The unmarried king also knew that his dynasty needed an heir. In April 1938, 42-year-old King Zog (a Muslim) married 23-year-old Countess Geraldine Apponyi de Nagy-Appony, a Catholic and daughter of a Hungarian nobleman and his American wife.

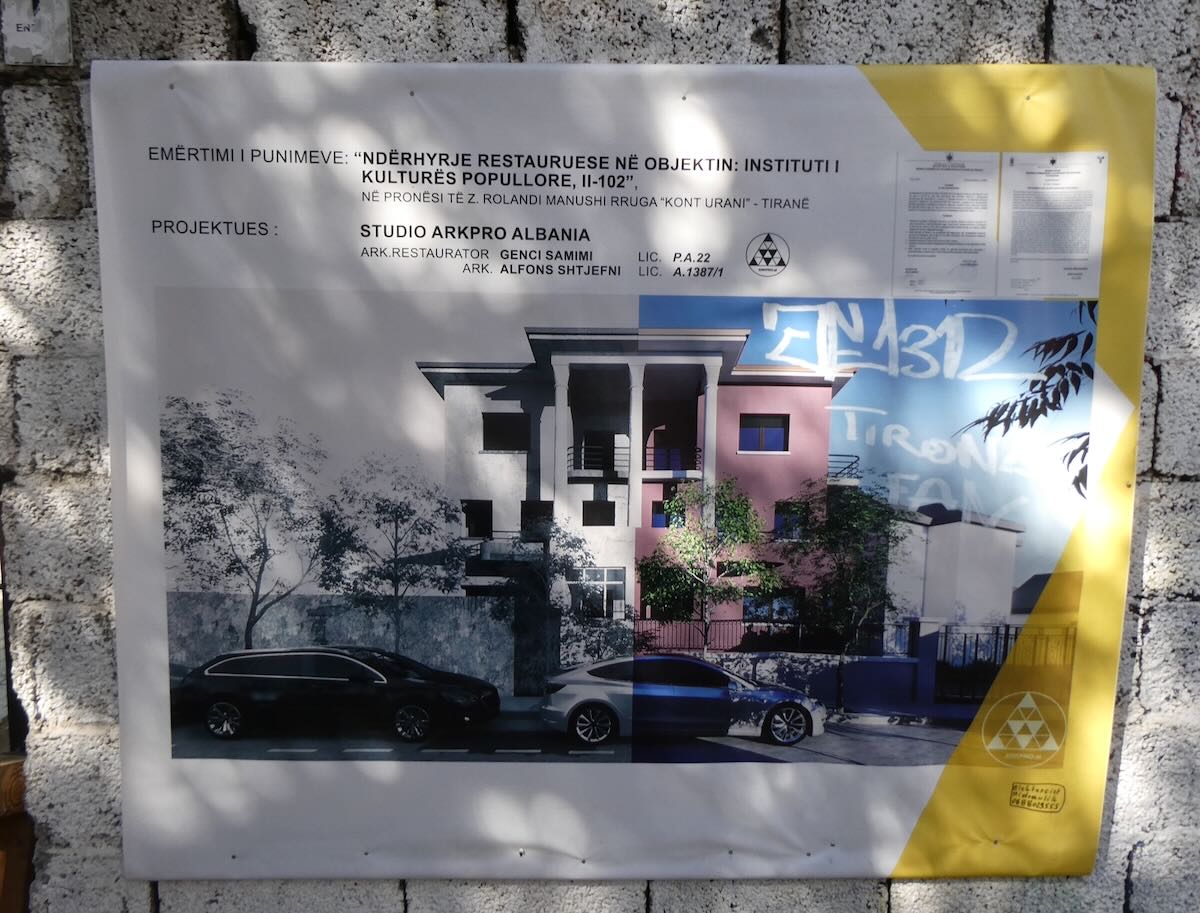

Meanwhile Albania was slowly entering the modern world and that included radio broadcasting. In 1937, a new radio-telephone station was installed outside of Tirana. The three-kilowatt shortwave transmitter was also used to broadcast several hours of programming per day, but it wasn’t a formal radio station. In the early 1930s several four-story Italian style villas had been built along Kont Urani Street, not far from Skanderbeg Square. In 1938, King Zog’s government confiscated one of the buildings, the Italian-Albanian Culture Center, and made it the first home of Radio Tirana. The new station was officially inaugurated by King Zog and Queen Geraldine in a live ceremony on 28 November 1938. A few months later, on 5 April 1939, the station had its first news scoop when it announced the birth of Crown Prince Leka to the world.

Queen Geraldine and King Zog at the 1938 inauguration of Radio Tirana.

The prince’s birth was good news for Albania, but it was a dark time in Europe. Just a few weeks earlier Adolf Hitler’s Nazi army had marched into Czechoslovakia without consequences. Not to be outdone by his German counterpart, on 7 April (two days after the prince’s birth), Mussolini invaded Albania. The Italian plans had been drawn up quickly and haphazardly and would likely have failed against a formidable opponent. But the handful of patrol boats in Albania’s navy could do nothing to stop the two battleships, six cruisers, nine destroyers, and numerous smaller ships that carried the invasion force across the Strait of Otranto. And Albania’s tiny poorly trained army was no match for the 100,000 troops that came ashore. In just a few days Albania had been overrun and King Zog and his family had fled to Greece (and eventually to England).

What happened over the next few years is a complex story. Mussolini’s goal was to turn Albania into an Italian client-state. The invaders set about to Italianize the country while also benefiting from its resources and workforce. As Radio Tirana was a key part of that process, the Italians modernized the studios, installed new antennas and transmitters throughout the country, and professionalized the programming. In order to not alienate the population, the station tried to maintain a balance between promoting Italian culture while also carrying Albanian culture and music.

Meanwhile, a resistance run by loyalists to King Zog fought back. They had some initial successes but soon the Italians quashed the movement by killing or capturing most of its leadership. They hadn’t made much effort to hide what they were doing. That should have ended the resistance but a new force, Albania’s tiny Communist Party, stepped in to fill the leadership vacuum. Unlike King Zog’s men, they already knew how to operate an underground movement. Gradually the Communists formed an effective guerilla force in Albania’s mountainous interior.

Italy’s surrender to the Allies in September 1943, should have been good news for Albania but the Nazis quickly sent in troops to take over and prevent the Allies from moving in. Their rule was more brutal than anything the Italians had done and that pushed more Albanians to join the resistance. By October 1944 the movement had grown to the point that its leaders had the confidence to launch an all-out attack on Tirana. For three weeks fighting raged back-and-forth in the city streets until on 17 November the last German troops withdrew under the cover of darkness. Tirana was once again ruled by Albanians and one of the leaders was a man named Enver Hoxha.

Albanian partisans in front of Radio Tirana after liberating the city. Tirana was the only European capital freed by its own partisan forces without any help from Allied armies.

Enver’s Place

My glass of raki is empty and I have all the pictures I want. I hand a generous tip to one of the bartenders. He was kind enough to move some bottles so I could get a clear picture of the “Radio Bar” sign. I continue up the street in the direction I had been heading and a block later come to my next destination, the house where Enver Hoxha lived while he ruled Albania.

The house doesn’t look at all like the sort of place a national ruler would live, let alone one who ruled with a deadly iron fist. It’s more like the kind of Frank Lloyd Wright inspired house that might be found in an upscale American suburb. Next door is the Abraham Lincoln Center, a school that teaches American English to Albanians. It’s a good thing, I think, that Enver Hoxha is dead. Enver hated the United States and he would never have been happy with these neighbors.

Unfortunately, the house is not open for tours so all I can do is stand outside and take pictures. As I look at the house I think back again to Radio Tirana. I hadn’t planned to visit any radio stations on this trip but the raki is still having its effect on me. Just for fun, I open up Google Maps and type in Radio Tirana. Surprisingly, I get a result and it’s only two blocks further down the same street. But the huge Radio Televizioni Shqiptar building on the corner with Rue Ismail Quemal turns out not to be the Radio Tirana building I had seen in the old picture in the national museum.

Inside, two young women are working at the reception desk and one speaks excellent English. I explain how I used to listen to Radio Tirana on shortwave. Unlike the bartenders, she knows all about it even though she is clearly in her early 20s. She says that in those days Radio Tirana would have been broadcasting from the old building near Skanderbeg Square. I’m about to leave but then I turn around. “Does that old building still exist? I would really like to see it if it does.”

Inside, two young women are working at the reception desk and one speaks excellent English. I explain how I used to listen to Radio Tirana on shortwave. Unlike the bartenders, she knows all about it even though she is clearly in her early 20s. She says that in those days Radio Tirana would have been broadcasting from the old building near Skanderbeg Square. I’m about to leave but then I turn around. “Does that old building still exist? I would really like to see it if it does.”

The young woman takes out her phone and pulls up an Albanian language newspaper article from 2021 with pictures of an abandoned dilapidated building. She sends me the link and on Google Maps points out the approximate area where the building stands, about a ten-minute walk away. I head out the door. The main street in the area she pointed out is a collection of modern restaurants, banks, and shops, but the side streets hold some old buildings. None of them, however, match the photos in the article. I give up and head back to my AirBnB.

Photo from the 12 January 2021 issue of Tirana’s Gazeta Si newspaper.

Later that evening I try to copy the article into Google Translate in order to read it. That doesn’t work as the web developer had disabled copying in the newspaper’s website. No problem. There are ways around that. I save the webpage to my hard-drive, open the file in a text editor, and then painstakingly delete all the HTML code to get clean Albanian text which I can now paste into Google translate one paragraph at a time. The article gives a summary of Radio Tirana’s history and says that the old building will soon be torn down. Mostly it’s an editorial decrying how so many historical buildings in Tirana have been demolished to make way for modern construction. The author pleads for more effort to be made to preserve and repurpose structures such as the old Radio Tirana building.

I then pull up Google Street View and begin perusing the streets of that neighborhood. Within a minute I find a building that clearly matches the one in the picture. I had walked by the spot several times. But the images are several years old. Maybe it has already been torn down.

The next morning I head straight back to the neighborhood. I see why I had missed the building the day before. Scaffolding has been erected in front of the building and then covered with thin fabric. A poster with two official-looking documents in Albanian has been placed on the wall that surrounds the site. Google Translate does its work again and I learn that the old Radio Tirana building has been saved. It’s to be renovated and turned into a cultural center. And that is ironic as that is what the building was originally built to be.

After the Liberation

After liberating Tirana, the Albanians joined forces with the Soviet army and Yugoslav partisans under Josip Tito to complete the liberation of Yugoslavia. But the Albanians were an enigma to the Russians and to the Yugoslavs. Remarkably, not only had none of the Albanian Communists ever visited the Soviet Union, but none of them had ever had contact with fellow Communists in other countries. The Albanian Communist movement was completely homegrown. But as the three groups fought side-by-side Enver Hoxha solidified his position at the top of the Albanian leadership and gained the trust of the Soviets.

When the war ended, the Western powers jockeyed with Stalin’s Russia over who would dominate the countries of central and eastern Europe. But little thought was given to little out-of-the-way Albania. Tito made a serious attempt to have Albania incorporated into Yugoslavia as that country’s seventh member republic. But Stalin stood behind Albania and for that Enver Hoxha became a staunch hardline Stalinist. (This was one of the factors that caused Tito to break with the USSR in 1948.)

Enver Hoxha modeled his rule and his plans for Albania on Stalinist Russia. He was likely the only Communist leader truly saddened by Stalin’s 1953 death. Then over the next few years Hoxha became increasingly dismayed as Khrushchev moved the USSR away from doctrinaire Stalinism. Hoxha completely broke with the Soviets in 1961, but in the meantime he had found a new friend in Mao’s Communist China.

The partnership between little Albania and the world’s most populous country proved to be mutually beneficial. China gained a diplomatic ally and an important base in another part of the world. And Albania got … well … goodies. The Chinese shipped grain to Albania, armed its military, developed mines, and built hydroelectric dams.

In 1965 a new Chinese-built state-of-the-art broadcast center was opened in Tirana and over the next few years the Chinese upgraded Albania’s existing transmitter sites so that by 1969 the country had forty-four shortwave transmitters and eight more on medium-wave. The 500-kilowatt medium-wave transmitter in Durres was among the most powerful in Europe. The transmitters were used both to relay Radio Peking (as it was then called) and to broadcast Radio Tirana in multiple languages. One of the smallest and poorest countries in Europe now had one of the most powerful international broadcasting transmitter sites in the world.

Enver Hoxha was, if nothing else, consistent in his dedication to Stalinist Communism. When China began forming a relationship with the United States in the 1970s, Hoxha saw that as a betrayal. He continued to work with China for several years but the relationship grew increasingly strained until all connections between the two countries were severed in 1978. Tiny Albania would go it alone against the rest of the world. And Radio Tirana would have exclusive use of all those Chinese-made transmitters.

Chinese-made 601-C military radio used by the Albanian army in the 1960s. Per the display it used 14.400 kHz with 42 watts.

Wait … What Did I Just Write?

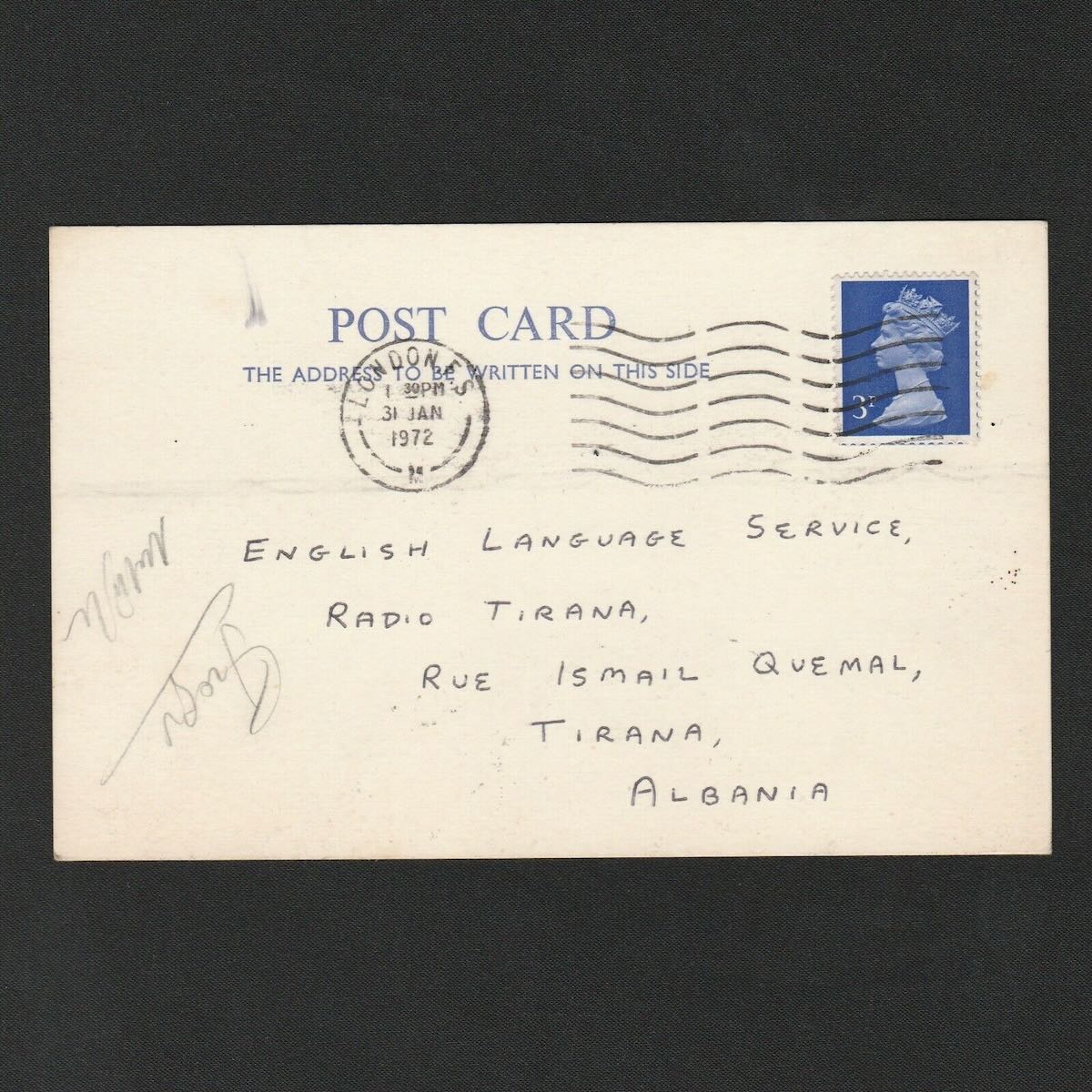

“In 1965 a new Chinese-built state-of-the-art broadcast center was opened in Tirana …” Oh. I began DXing in 1971 and I remember listening to Radio Tirana in the 1970s and 1980s. When I was in Tirana I assumed that the station had broadcast from the old villa until the end of the Communist era. But now, weeks later while doing background research, I realize the truth. The Radio Tirana I knew broadcast from the big cement building on Rue Ismail Quemal. If I had known at the time of my visit I would have asked the young woman if I could get a tour of the building. Now it’s too late. But I really enjoyed Albania and plan to go back. Next time.

Our Fascination with Radio Tirana

In the 1970s and 1980s the shortwave bands were filled with international broadcasters and there was nothing particularly memorable about most of them. Radio Tirana was different. If you were listening to shortwave in that era you remember Radio Tirana. It was not like any other broadcaster. It had a unique personality and certainly a unique political perspective. I never would have gone out of my way to locate the original building of Radio Portugal or Radio Budapest. But doing so for Radio Tirana excites the imagination.

I remember the main lady announcer with Radio Tirana’s English service had a very warm voice. We now know that her name was June Taylor and she was from New Zealand. She used to address the audience as “Dear Listener” and we joked that she knew the station only had one listener. The strident programming felt both comical and very serious. When other Eastern bloc stations used terms like “imperialists” and “aggressors” it felt as if the announcers were just reading from a translated script. When Radio Tirana used phrases like that there was an earnestness to it that the other stations didn’t have.

Radio Tirana represented an evil government. Enver Hoxha’s rule was brutal in every way. The National Museum on Skanderbeg Square has an entire room dedicated to the victims of his regime. The walls are covered with long lists of all the known victims of the period plus photos of the labor camps and of a small sampling of the thousands of Albanians who died in those camps. It’s a sobering place to visit.

Yet there was something to be admired in this tiny country and its plucky tinpot dictator willing to go it alone and thumb his nose simultaneously at the USA, the USSR, and China. We like the underdog even if he’s crazy. And maybe that’s precisely what made Albania and Radio Tirana so interesting. Enver Hoxha stood up to everyone.

But unlike the crazies of today such as Iran and North Korea, tiny Albania never threatened anyone. And after Stalin told Tito to keep his hands off the country, no one ever threatened Albania either. Still, wrapped up in his own paranoia and delusions, Enver Hoxha kept his people constantly focused on keeping Fortress Albania safe from enemies, foreign and domestic. Yet Enver Hoxha never became seriously involved with undermining other governments or providing weapons to guerillas in distant lands.

Due to Albania’s small size, Enver Hoxha had just one weapon that he dared to wield against the rest of the world: the broadcasts of Radio Tirana. And with those powerful Chinese-built transmitters they did it very effectively.

To SWLs and DXers, Radio Tirana was interesting but not something to be taken too seriously. However, around the world there were radical activists who agreed with Enver Hoxha’s politics and admired him for his fearlessness in standing up to more powerful nations. They didn’t want their version of Marxism to be run from Moscow or Beijing either. They were Radio Tirana’s real audience. Thus Albania had an influence in revolutionary movements around the globe far greater than could be expected given the country’s tiny size.

And that just might answer a mystery. Who tied a Brazilian flag to the scaffolding in front of the old Radio Tirana building?

I have no idea how the flag got there. But there is a story that I want to believe. In the 1970s a Marxist guerilla movement operated in the jungles around the Araguaia River in central Brazil. The movement identified with Enver Hoxha and so the guerillas would have listened to Radio Tirana’s Portuguese broadcasts. Picture a gray-haired former guerilla finding his way to Tirana and then tying the flag there in memory of his fallen companions. That would be a real legacy for Radio Tirana.

Next: Part Two “Bunkers and Bugs.”

Links and Other Info

- The 2021 newspaper article about Radio Tirana.

- The Instituto Luce has six pages of black and white photos of Radio Tirana facilities and personnel taken in 1940 to 1942 during the Italian occupation.

- More photos of the old Radio Tirana building and of transmitter sites outside Tirana.

- Interview from 2022 with Radio Tirana announcer June Taylor.

- SWLing Post discussion on Radio Tirana announcers from 2023.

- Recording of 1968 Radio Tirana broadcast with photos of Tirana.

- Recording of 1976 sign-on by Radio Tirana.

- Article “Re-tuned to Radio Tirana” from 2019.

- Short article on Radio Tirana’s political influence.

- Academic article on the history of broadcasting in Albania [PDF].

- Location of original Radio Tirana building on Google Maps.

- Location of the new Radio Tirana building on Google Maps. Oddly, Google Maps does not show a building outline here but if you switch to satellite view the building is there. It can also be seen on Street View.

- Location of the Radio Bar Tirana on Google Maps.

- The Radio Bar.

- Anthem of the Albanian Partisans of World War II.

- This album by Italian Jazz musician Enrico Blatti contains a song named “Radio Tirana.”

- A recording of Enrico Blatti’s song “Radio Tirana.”

- Radio Tirana recordings on the Shortwave Radio Audio Archive

A great report, thanks Don. This and a recommendation in Lonely Planet meant I had to check out Radio Bar.

And here I am as I type: inside that very bar a year later: enjoying the radios, film posters, furniture and a smooth Albanian red wine. Will share my experiences with Spectrum Monitor magazine readers in the June issue.

Great research and writing! Thanks for sharing.

Prezado Don,

Muito obrigado por compartilhar mais um registro épico. Não perco nenhuma publicação.

Sou brasileiro, e apesar do contexto histórico complexo envolvendo o terrível ditador e ambas as ditaduras, fiquei surpreso com a presença do Brasil num local tão distante e histórico.

Ansioso pela parte 2.

Grande abraço

SUCH a great article, Don. As always the amount of detail you include is incredible along with great storytelling.

I’m going now to snag your book and look forward to you getting you to sign it for me at the next fest.

Scott

Radio Tirana put out a colossal signal right in the SSB section of the 40 Metre Amateur Band. It was a good test of receiver performance trying to copy other hams as close in to Radio Tirana as possible. I went over to using Ten Tec transceivers at that time as they were one of the few brands with good enough receiver dynamic range to cope.

You write well and tell an entertaining and educational story. I’m looking forward to Part 2.

Very interesting story. I remember listening to their broadcasts and their stubborn(?) history.

Wow, what a wonderful story and history lesson in radio and the cultural events that shaped Albania right down to the Brazilian flag hung at the radio Tirana broadcast site , in tribute to the memory of Enver Hoxha!? For the rebel movement into Brazil, and the connection with Mao Zedong and China wonderful story. I really enjoyed it. Thank you.. plus a very honored QSL card.

Wonderful article! Thank you. I used to hear Radio Tirana too. And I remember there was a time when Tiran relayed Radio Peking.

(Not that it matters, but I can’t help noticing that the drink Albanians call ‘raki’ is not the same as the Turkish ‘rak?’. The latter has anis, hence whitens when water is added, like many others around the Mediterranean, the Greek ouzo, and Arab arak for example.)

Thank you so much for the wonderful time i had reading your detailed and excellent article on what was one of the most distinctive voices of the cold war.

WPC3SWL

Don, this post is absolutely phenomenal! Reading it brought back so many memories of my own listening to Radio Tirana in the early ’80s. I’d sit in my bedroom with my trusty Zenith Transoceanic, captivated by the unique personality of the broadcasts. Your vivid descriptions and the historical context made me feel like I was right there with you, walking the streets of Tirana.

Thank you for sharing these incredible photos and for crafting such a compelling travelogue—it’s a true gift to our readers. I’m already looking forward to Part Two!

Cheers,

Thomas