The Cambodian government has ordered local radio stations to stop broadcasting foreign programs ahead of general elections in a move widely seen as a major setback to media freedom in the country and aimed at stifling the voice of the opposition.

Prime Minister Hun Sen’s administration on Tuesday asked all FM stations to cease rebroadcasting Khmer-language radio programs by foreign broadcasters in the run-up to the July 28 elections, saying the move was aimed at “forbidding” foreigners in Cambodia from campaigning for any group in the polls.

Local stations who flout the order face legal action.

“Upon receiving this directive, I would like to ask that all the directors of FM station to implement it accordingly,” acting Information Minister Ouk Pratna said in issuing the order.”If any station doesn’t follow this directive, the Ministry of Information will take legal action against it according to the existing law.”

Khmer programs of at least three foreign broadcasters—U.S.-based Radio Free Asia (RFA) and Voice of America (VOA), as well as Radio Australia—will be barred from being aired under the directive.

Three other foreign broadcasters—the state-run Voice of Vietnam and China Radio International and French public radio station RFI—will not be affected as they operate their own stations in Cambodia.

Move ‘questions legitimacy’ of elections

The U.S. government immediately lodged a protest with the Cambodian authorities over the directive, saying it will throw in doubt the legitimacy of the elections, in which Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) is widely expected to win, enabling him to extend his 28 years in power.

The CPP has won the last two polls by a landslide despite allegations of fraud and election irregularities.

“The directive is a flagrant infringement on freedom of the press and freedom of expression, and is yet another incident that starkly contradicts the spirit of a healthy democratic process,” John Simmons, spokesman for the U.S. Embassy, said in a statement.

“While Royal Government officials at the highest levels have publicly expressed an intention to conduct free and fair elections, these media restrictions, and other efforts to limit freedom of expression, will seriously call into question the legitimacy of the electoral process,” he said.

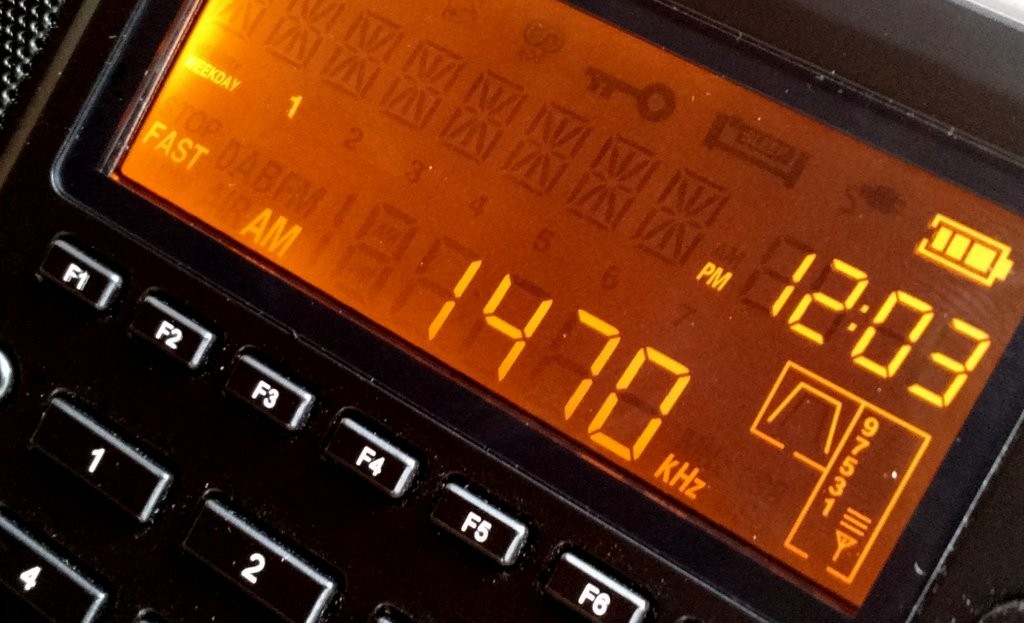

About 10 local FM stations carry Khmer programs by RFA, which also broadcasts on shortwave in Cambodia.

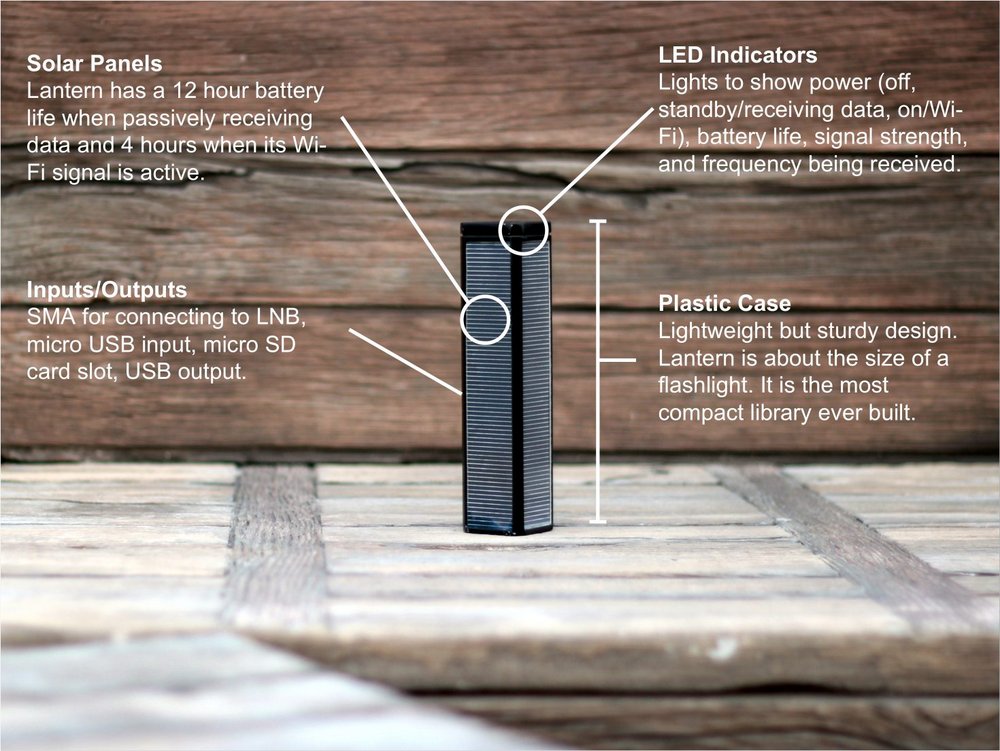

RFA said in a statement that it “remains committed to bringing objective, accurate, and balanced election coverage to the people of Cambodia at this critical time” and vowed that it “will do so on every delivery platform available.”

“The Ministry of Information’s directive doesn’t stem from complaints of programming irregularities, but rather is a blatant strategy to silence the types of disparate and varied voices that characterize an open and free society,” it said.

Beehive Radio

Mam Sonando, a Cambodian activist who runs the independent Beehive Radio and an ardent critic of Hun Sen’s administration, called the ban “illegal” and “childish” but added that he would comply with the order.

He said the order would hurt political parties scrambling to convey their messages to the people ahead of the elections.

Mam Sonando, who owns Beehive Radio, told RFA earlier this week that the Information Ministry is restricting overseas groups from buying airtime at Beehive Radio and had turned down requests to set up relay stations to beam to the provinces.

U.S.-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) said it was puzzled by the Cambodian government’s suggestion of foreign meddling in the elections.

“There has been no history in Cambodia of foreigners participating on a partisan basis in elections,” said Brad Adams, executive director of Asia Division. “What this is really about is they don’t want foreigners coming in and observing the elections and then doing their job independently and professionally and then reporting their results.”

He said the Hun Sen government was trying to prevent reporting of events leading up to the elections.

“It’s about the fact that they know the elections are going to be very poor—they are structurally poor, they are poor in implementation and poor in practice and they don’t want this reported,” Adams said.

“The problem is that the world doesn’t work like that anymore. They can’t keep the eyes and ears of the world out. So, the reality is going to be reported.”

The Cambodian government has ordered local radio stations to stop broadcasting foreign programs ahead of general elections in a move widely seen as a major setback to media freedom in the country and aimed at stifling the voice of the opposition.

Prime Minister Hun Sen’s administration on Tuesday asked all FM stations to cease rebroadcasting Khmer-language radio programs by foreign broadcasters in the run-up to the July 28 elections, saying the move was aimed at “forbidding” foreigners in Cambodia from campaigning for any group in the polls.

Local stations who flout the order face legal action.

“Upon receiving this directive, I would like to ask that all the directors of FM station to implement it accordingly,” acting Information Minister Ouk Pratna said in issuing the order.”If any station doesn’t follow this directive, the Ministry of Information will take legal action against it according to the existing law.”

Khmer programs of at least three foreign broadcasters—U.S.-based Radio Free Asia (RFA) and Voice of America (VOA), as well as Radio Australia—will be barred from being aired under the directive.

Three other foreign broadcasters—the state-run Voice of Vietnam and China Radio International and French public radio station RFI—will not be affected as they operate their own stations in Cambodia.

Move ‘questions legitimacy’ of elections

The U.S. government immediately lodged a protest with the Cambodian authorities over the directive, saying it will throw in doubt the legitimacy of the elections, in which Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) is widely expected to win, enabling him to extend his 28 years in power.

The CPP has won the last two polls by a landslide despite allegations of fraud and election irregularities.

“The directive is a flagrant infringement on freedom of the press and freedom of expression, and is yet another incident that starkly contradicts the spirit of a healthy democratic process,” John Simmons, spokesman for the U.S. Embassy, said in a statement.

“While Royal Government officials at the highest levels have publicly expressed an intention to conduct free and fair elections, these media restrictions, and other efforts to limit freedom of expression, will seriously call into question the legitimacy of the electoral process,” he said.

About 10 local FM stations carry Khmer programs by RFA, which also broadcasts on shortwave in Cambodia.

RFA said in a statement that it “remains committed to bringing objective, accurate, and balanced election coverage to the people of Cambodia at this critical time” and vowed that it “will do so on every delivery platform available.”

“The Ministry of Information’s directive doesn’t stem from complaints of programming irregularities, but rather is a blatant strategy to silence the types of disparate and varied voices that characterize an open and free society,” it said.

Mam Sonando

Mam Sonando, a Cambodian activist who runs the independent Beehive Radio and an ardent critic of Hun Sen’s administration, called the ban “illegal” and “childish” but added that he would comply with the order.

He said the order would hurt political parties scrambling to convey their messages to the people ahead of the elections.

Mam Sonando, who owns Beehive Radio, told RFA earlier this week that the Information Ministry is restricting overseas groups from buying airtime at Beehive Radio and had turned down requests to set up relay stations to beam to the provinces.

Election reporting

U.S.-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) said it was puzzled by the Cambodian government’s suggestion of foreign meddling in the elections.

“There has been no history in Cambodia of foreigners participating on a partisan basis in elections,” said Brad Adams, executive director of HRW’s Asia division. “What this is really about is they don’t want foreigners coming in and observing the elections and then doing their job independently and professionally and reporting their results.”

He said the Hun Sen government was trying to prevent reporting of events leading up to the elections.

“It’s about the fact that they know the elections are going to be very poor—they are structurally poor, they are poor in implementation and poor in practice and they don’t want this reported,” Adams said.

Cambodian Center for Independent Media Director Pa Nguon Teang said the ban was aimed at curbing the views of the opposition in the country.

Freedom of the press has increasingly declined in the country, with reporters exposing government corruption and other illegal activity coming under deadly attack and facing death threats, including from the authorities, according to a rights group and local journalists.

Stifling ‘opposition radio’

Pa Nguon Teang felt the directive was specifically aimed at RFA and VOA.

“The ban intends to stifle the voice of RFA and VOA because the government has regarded the two stations as opposition radio stations,” he said, adding that by preventing local stations from carrying programs by the two entities, the government believes it can “silence” the opposition parties.

Local rights group Adhoc’s chief investigator Ny Chakriya said the ministry’s ban is “not based on any applicable laws,” pointing out that “it is illegal and can’t be enforced.”

“The ban is against the constitution because the constitution guarantees freedom of expression,” he said.

Moeun Chhean Nariddh, director of the Cambodia Institute for Media Studies, also called the move a violation of the constitution.

“Any order preventing media dissemination is against the constitution,” he said.

Reported by RFA’s Khmer Service. Translated by Vuthy Huot and Samean Yun. Written in English by Parameswaran Ponnudurai.