Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Don Moore–noted author, traveler, and DXer–for the latest installment of his Photo Album guest post series:

Don Moore’s Photo Album:

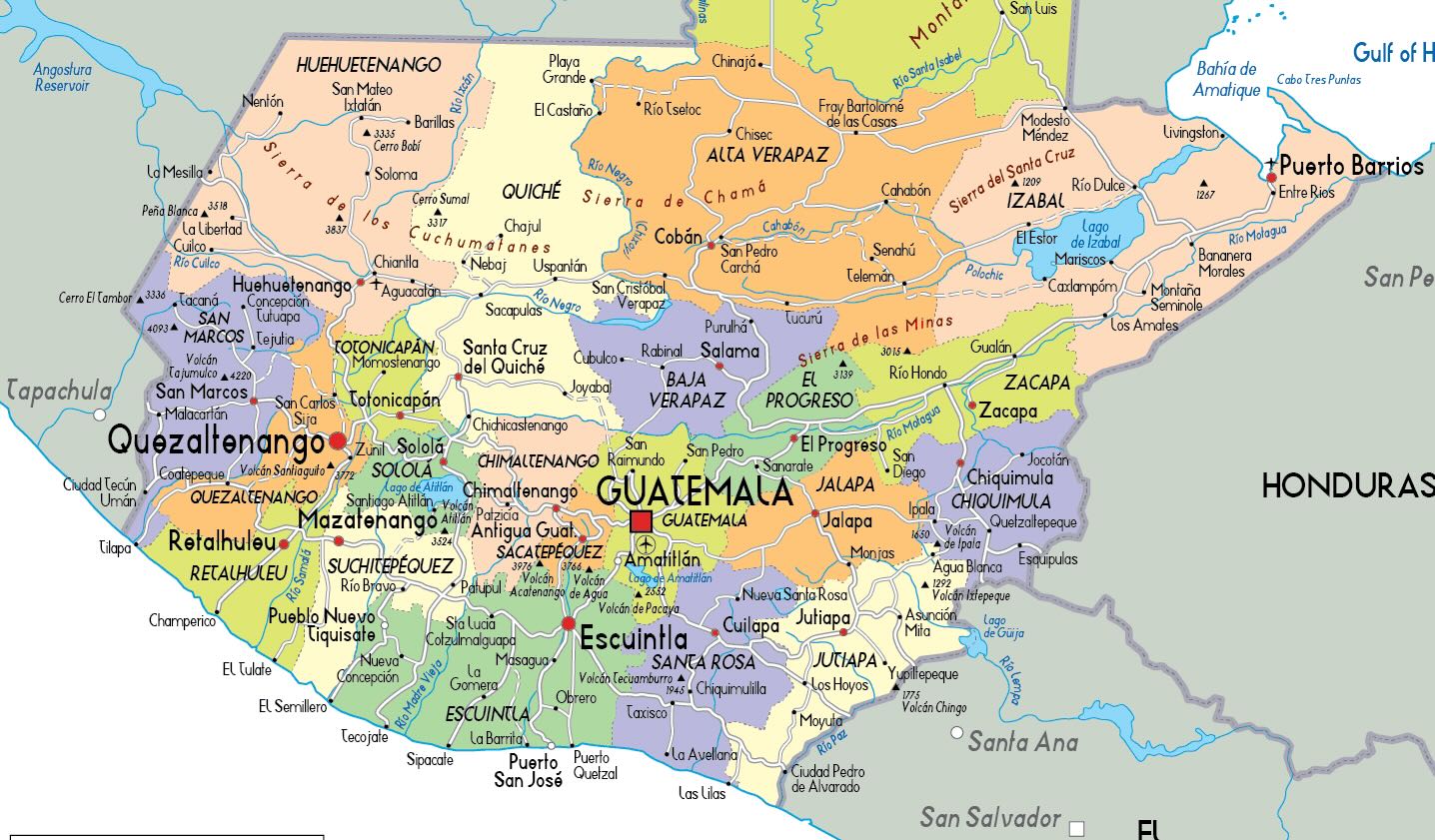

Guatemala (Part Four) – To the Western Highlands

More of Don’s traveling DX stories can be found in his book Tales of a Vagabond DXer [SWLing Post affiliate link]. If you’ve already read his book and enjoyed it, do Don a favor and leave a review on Amazon.

If anyone deserves recognition as the first tourists to visit western Guatemala it would be the American John Lloyd Stephens and Englishman Frederick Catherwood. In the 1820s and 1830s, Stephens traveled extensively in Europe and the Middle East and published several books about his journeys. On one of those trips he met Catherwood, an accomplished artist who traveled around the Mediterranean making drawings of archaeological sites.

The pair decided to visit Central America after coming across accounts of ruins in the region by the Honduran explorer Juan Galindo. Their trip received official support when U.S. President Martin van Buren appointed Stephens as a special ambassador to Central America. The two men wandered the region for several months in 1839-40 visiting known Mayan sites and rediscovering many others. Stephens wrote two books about their travels, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán and Incidents of Travel in Yucatán while Catherwood published a book of his drawings, Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan. All three books became immediate bestsellers.

The three books introduced the Mayan civilization to the rest of the world for the first time, bringing new visitors to the region. Some came to do serious research. Others were just curious adventurers. But the numbers that came were small as only a few wealthy people had the time and money to journey to exotic places.

Then the 1960s brought a new kind of tourist – the hippie. Many young people in Europe and North America saw flaws in the materialism of their own societies and became interested in experiencing non-western cultures. The Mayan region of Guatemala was a perfect destination. It was exotic, relatively easy to get to, and cheap.

That qualification of cheap was especially important. The hippies weren’t big spenders staying in classy hotels and eating at pricey restaurants. They found rooms in basic hospedajes and ate everyday local food cooked by indigenous women at roadside comedores. In many ways that was better. The money went directly to local working people instead of to the wealthy owners of fancy establishments.

The 1960s and 1970s became the era of hippie tourism in Guatemala. Most of visitors went to the area around Lake Atitlán, drawn by the lake’s natural beauty and the region’s year-round springlike climate. The epicenter of it all was the little lakeshore village of Panajachel.

Clouds of War

To anyone wandering the shoreline of Lake Atitlán in the mid-1970s, Guatemala seemed to be a peaceful place. In reality, a guerilla war was raging just a hundred kilometers away. In 1954, a CIA-sponsored coup overthrew Guatemala’s elected government and ushered in a long period of repressive military regimes. With the military showing no signs of relinquishing power, around 1965 a few leftist activists went into the remote mountains of northern Huehuetenango and Quiché departments with hopes of repeating Fidel Castro’s success in Cuba.

By all appearances, this should have been a minor footnote in Guatemala’s history. The would-be revolutionaries, after all, were city people without the skills to survive in the remote mountain highlands. But they recruited a few Mayans to their movement and then a few more until the Mayans dominated the guerilla movement. Yet the Mayans were never guided by ideology. The guerilla movement was a way of fighting back against centuries of repression, discrimination, and poverty. As one observer put it, “They’re Communists because of their stomachs, not because of their heads.”

As the guerilla movement grew the combat zone gradually moved south and into other regions. And the war became less a political revolution than an ethnic conflict. The military was dominated by Spanish-speaking ladinos who knew nothing of Mayan culture or the Mayan languages. All Mayans were seen as potential enemies, as was anyone who attempted to improve the Mayans’ lives. That lead to the formation of military-run death squads which targeted small town mayors, teachers, social workers, church leaders, and anyone else who dared to speak up. By 1981 over two hundred non-combatants were being kidnapped, killed, and dumped by the side of the road every month.

In 1976 the Lake Atitlán region had been seen as a peaceful place. A few years later the combination of active military death squads in the villages along the lake and a widening guerilla war elsewhere had put an end to that image. The era of hippie tourism in Guatemala was over.

Lake Atitlán 1983

When I arrived in Panajachel for the first time in June 1983, the village felt like a ghost town. There were, at most, fifteen or twenty foreign visitors. Many restaurants and shops were closed. The owners of those that remained were desperate for any business that came their way. I got a room for $1.50 a night at a tiny hospedaje at the end of a shaded footpath.

Panajachel was peaceful. A new military government that came to power in March 1982 had ended death squad activity in the towns and cities. (Instead they were pursuing an even more aggressive war against remote mountain villages. But that hadn’t come to light yet.) Guerillas occupied the mountains that I could see on the south side of the lake. But the army had several bases nearby so no one was worried about them.

I had come to Panajachel to visit La Voz de Atitlán, a small Catholic broadcaster on 2390 kHz. The radio station was part of a larger mission that provided education and health services to the Tzutuhil Mayan people who lived in and around the town of Santiago Atitlán on the south side of the lake. The project was sponsored by the Diocese of Oklahoma in the United States and beginning in 1968 had been directed by Father Stanley Rother. Some DXers had received QSLs signed by the priest. In June 1981, military death squads murdered Father Rother in the church rectory.

The full account of what happened at La Voz de Atitlán and of my quest to visit the station is long, complex, and highly personal. My two attempts to visit the station in 1983 both failed. I finally made it in December 1987 but then we were accidentally stranded in the town overnight while it was under military occupation. Back home a month later, we heard a report on National Public Radio that fourteen people in Santiago Atitlán had been killed by the death squads in that month of December. The entire story is Tales of a Vagabond DXer.

Photos of the station from 1987. Juan Ajtzip was the station manager for many years. Note the handmade weaving on the wall.

La Voz de Atitlán, 2390 kHz, as heard in Pennsylvania on 25 December 1979 at 0355 UTC:

Thirty minutes of La Voz de Atitlán, 2390 kHz, recorded in Iowa on 27 January 1993 from 0241 to 0311 UTC:

La Voz de Atitlán pennant via Jerry Berg.

La Voz de Atitlán pennant via Jerry Berg.

Station envelope via Dave Valko.

The Catholic church in Santiago Atitlán today (from the Diocese of Chimaltenango website)

The People of Santiago Atitlán

These pictures evoke what daily life was like in Santiago Atitlán in the 1980s. My favorite is the one that shows three women carrying jugs of water on their heads. Given the shape of the jugs you would assume they are made of clay. I did the first time I saw them. But the jugs are made of plastic and that is very significant.

When people do not live next to a water source, water has to be carried back to the home. It’s a job that is almost always assigned to the women. For thousands of years the task was done with clay jugs. Carrying a heavy clay jug to a water source is hard work. Carrying it home filled with water is harder. And the weight of the jug limits how much water can be carried on each trip. The women have to make multiple trips day after day after day for their entire lives.

Plastic jugs require no effort to carry to the water source and add no additional weight to the load on the way home. That means less effort and fewer trips for the same amount of water. Less weight and fewer trips mean less stress on the women’s bodies. It has been estimated that the simple plastic water jug has added several years to women’s lifespans in the poorest parts of the Third World.

Plastic water jugs are never included on lists of the greatest inventions in human history. That may be because such lists are usually compiled by men.

Next: Part Five – Visiting Nahualá

Links

- A Brief Summary of Stephens and Catherwood’s expedition.

- Downloadable electronic copies of Incidents of travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan.

- A look at a copy of Frederick Catherwood’s book, Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan.

- Downloadable electronic copies of Frederick Catherwood’s book at archive.org.

- La Voz de Atitlán website

- La Voz de Atitlán Facebook page

- Spanish and Tzutuhil language documentary on the history of La Voz de Atitlán

- The Story of Father Stanley Rother

- Another Article about Father Rother

Don, decirte que me encantan los relatos de tus viajes en busca de emisoras de onda corta.

Enhorabuena, la forma de tratar la cultura y las gentes a los sitios que vas es increible y las fotos fantasticas, reflejan a la perfeccion la sociedades

Don, your excellent articles only make me want to travel more! Thank you So much for sharing these with our community.