This article originally appeared in the October 2014 issue of The Spectrum Monitor Magazine.

There’s a topic I’d like to put on table. One that, in my radio-centric world, stirs up a fair amount of discussion…and, truth be told, apprehension.

The question, simply put, is this: “Does shortwave radio have a future?”

I’m frequently asked this question on my blog, the SWLing Post. Somehow–although I’m not sure how–I’ve become something of a go-to individual when this topic arises, and find myself facing this question frequently.

In my work, I continue to regard shortwave radio as a relevant and contemporary medium that conveys information to all parts of the globe, regardless of where on earth one is born, and, for the most part, regardless of one’s income or status. I love the technology, the content, the variety, the affordability, the relevance, and (let’s face it) the sheer magic of shortwave radio. I love that the medium can help people, teach people, move and inspire people, all around the world, everyday–even in the midst of famines, disasters, crises, wars.

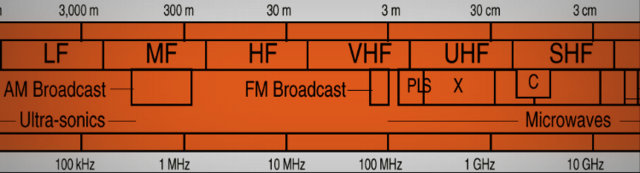

The shortwaves–which is to say, the high-frequency portion of the radio spectrum–will never disappear, even though international broadcasters may eventually fade into history. I often think of the shortwave spectrum as a global resource that will always be here, even if we humans are not. But on a brighter note, I expect the shortwave spectrum will be used for centuries to come, as we implement various technologies that find ways to make use of the medium.

So, in the broadest sense, yes; I sincerely believe shortwave has a future.

But that’s not really what most people are asking. Most want to know if there is anything out there to listen to–and what, if anything, will continue to be out there. Broadcasters have been using the shortwave medium for a long time to spread their message. And many of us (TSM and SWLing Post readers, for example) are still listening. At least, as long as the broadcasting, itself, continues.

Shortwave broadcasting: clearly on the decline

Just to be clear: when I refer to a shortwave broadcaster here, I refer to the large government-supported international broadcaster, unless I specify differently. (There are also many private, non-profit, and clandestine broadcasters; these I will address separately).

If you’re a dedicated shortwave radio listener, radio news just this year has been enough to squelch anyone’s enthusiasm for the future of the hobby. The Voice of America, with very little warning, dropped many of their shortwave services in the final week of June 2014, and now it appears that the Broadcasting Board of Governors’ (BBG), according to their special committee report, regard shortwave radio as a legacy technology with a dwindling listenership. They cite plummeting listener numbers around the world, despite an acknowledgement that there are still communities throughout the world who rely on shortwave.

Moreover, Radio Australia has also been hit hard with budget cuts via their parent Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). While there is no confirmation of a loss of shortwave services at time of writing, no doubt ABC also plans to reduce RA’s shortwave offerings significantly at some point.

And earlier this year after months of speculation, Voice of Russia suddenly dropped all of their shortwave radio services. I, for one, didn’t see that coming; I wouldn’t have guessed that VOR would drop shortwave completely. VOR, and its predecessor, Radio Moscow, have long been dominant voices on the shortwaves. Now they have fallen silent,* just as tensions between Russia and many other countries heat up.

[FOOTNOTE: *However, Voice of Russia may be relayed on the new shortwave broadcaster, Global 24.]

Radio Exterior de España, a broadcaster I’ve also listened to most of my life, has also just announced their closure (October 15, 2014).

Even the small non-profit clandestine station, Shortwave Radio Africa, sadly lost funding in August 2014, closing shop within the course of a few weeks; this was a particularly unfortunate event, as this station provided an alternative voice to government propaganda.

So, let’s face it–shortwave radio broadcasting is on the decline. It simply is. There is no denying this.

Hitting home

Clearly, there are not as many broadcasters on the air as there were in even the late 1990s, let alone as many as there were in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when as a child I began SWLing, and found the bands crowded with voices clamoring to be heard.

Now I’m finding it difficult to imagine a world without, for example, Radio Australia. I have tuned into RA on 9,580 kHz since I was eight years old; if I have a companion on the shortwaves, it’s surely Radio Australia. But I do have to come to terms with the idea that we may lose RA at some point, too–indeed, it’s most likely.

In the past five years I’ve had to say a painful goodbye to some of my favorite broadcasters: Radio Netherlands Worldwide, Radio Canada International, and Radio Bulgaria; at the same time, the BBC, DW, RFI, and the Voice of America have all decreased broadcasting hours, as well.

I find it sad to hear these stations fall silent, one by one. Perhaps because I’m something of an anachronism–a fellow who still uses shortwave radio as a means to understand the world, who still regards radio as a source of news that is…well…from the source.

Perhaps this is why I feel so compelled to archive shortwave radio broadcasts on the Shortwave Radio Audio Archive, why I especially want to hear the voice of each station preserved. And I hope this archive will also serve as a reminder that wireless information has been crossing the planet for the better part of a century, even faster than the Internet can disseminate it now. Shortwave still has this power.

What about private, independent broadcasters?

So far, I’ve been primarily addressing government broadcasting. But what about private shortwave broadcasters, who often rely on revenue from content providers and advertising? While struggling in some respects in this economy, private broadcasters are still prominent on the shortwave landscape.

I asked Jeff White, president of the private shortwave broadcaster WRMI about the current state of private broadcasting:

“There has been some decline in shortwave broadcasting among private broadcasters (primarily religious broadcasters). HCJB in Ecuador and FEBA in the Seychelles come to mind–also Christian Vision in Chile. But most of the privately-owned broadcasters seem to be in a status quo situation–not any significant decline, and not any significant growth. Of course you also have to consider the government broadcasters who have privatized their transmitter sites to separate companies, like Babcock, Media Broadcast, MGLOB in Madagascar, Sentech, TDF, etc. In that sense, there has been a great growth in private SW broadcasting, although Media Broadcast has closed a site or two and TDF closed their site in French Guiana (but they both are still very strong shortwave relay sites with lots of clients).”

Most private broadcasting sites were constructed with efficiency and profitability in mind, as compared with many government-funded broadcasting sites, which during the Cold War, built robust and even redundant systems to ensure their radio voice being heard across the planet.

As a case in point, Jeff White’s WRMI is the largest private broadcaster in North America, and one of the largest in the world–but it has much less overhead than, for example, the IBB’s Edward R. Murrow Transmission site in Greenville, North Carolina. According to Jeff White, WRMI sits on 660 acres (one square mile), whereas the IBB site encompasses 2,800 acres (4.4 square miles). While WRMI has more transmitters (fourteen, compared to IBB’s eight) the IBB maintains a larger antenna farm and larger transmitter building, with more employees. In short, the Edward R. Murrow Transmission Site was never designed for efficiency and profitability, whereas WRMI (and its predecessor WYFR) was.

But to be clear, I strongly believe the US should maintain and use the Edward R. Murrow Transmission site; this broadcasting site is simply too valuable a diplomatic resource to abandon. Moreover, in the past 40 years this site has undergone many updates and improvements which allows it to be operated 24/7 by a very small (and efficient) crew of dedicated employees. [Check out my virtual tour of the Edward R. Murrow transmission site to see this remarkable international broadcasting site first hand.]

Another difficulty inherent in private shortwave broadcasting is finding a way to fund it. Shortwave radio is difficult to monetize through promotional ads. After all, private stations typically broadcast to a vast audience; it’s hard to advertise a regional retailer or service when your footprint covers up to a third of the entire planet. And shortwave listeners are often “disenfranchised”; they have no means to purchase products. But conversely, the disadvantage is also an advantage–save the Internet, what media is so widespread–?

Private broadcasters, however, still maintain their services by brokering air-time to paying clients, many of whom have a religious affiliation, and by relaying language services for big government broadcasters who simply purchase transmitter time.

But then there are the mavericks, such as WBCQ in Monticello, Maine. This station is all about free speech, and maintains its site on a shoestring budget. The number and variety of shows they broadcast is nothing short of amazing. Looking at WRMI and WBCQ, it’s clear that government broadcasters could learn from these examples.

[Update: Check out the new commercial shortwave radio station, Global 24, broadcasting via WRMI.]

But is shortwave radio even relevant in the Internet age?

If you read the Shortwave Committee Report Fact Sheet the BBG recently published, you might be led to believe that shortwave should be replaced by more recent communications media. The report marks shortwave radio as a legacy technology, and claims that it is sunsetting with lesser relevancy each year. The BBG committee claims that listeners use mobile technologies and computers to access broadcasters around the globe.

There is some truth in this usage argument. If you randomly surveyed 1,000 people living in, for example, Seoul, Beijing, Bangkok, and Singapore, you would likely find very few–perhaps less than 1%–who still listen to shortwave radio. And it’s quite true that people gravitate towards the more accessible medium; in populated parts of the world where people live above the poverty line, you will find the market flooded with smartphones. In such cases, mobile Internet is certainly both financially and technologically accessible.

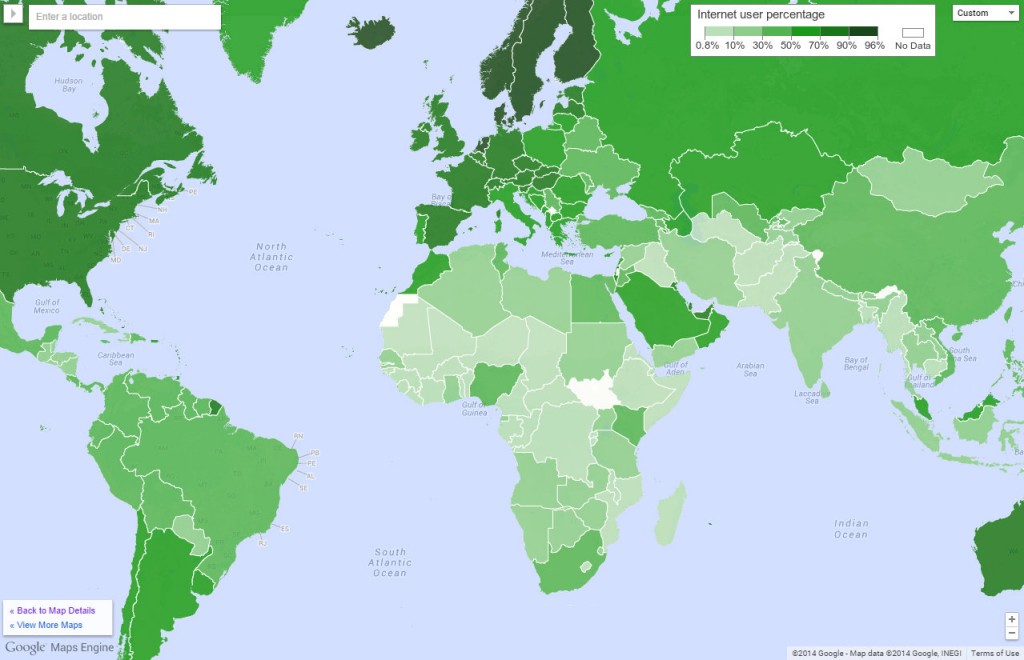

But although Internet penetration is increasing even in the developing world, it’s vital to note that since the birth of the Internet, invariably, poverty and Internet usage inversely correlate. In evidence, percentages of the global population with Internet access are indicated on this Google map:

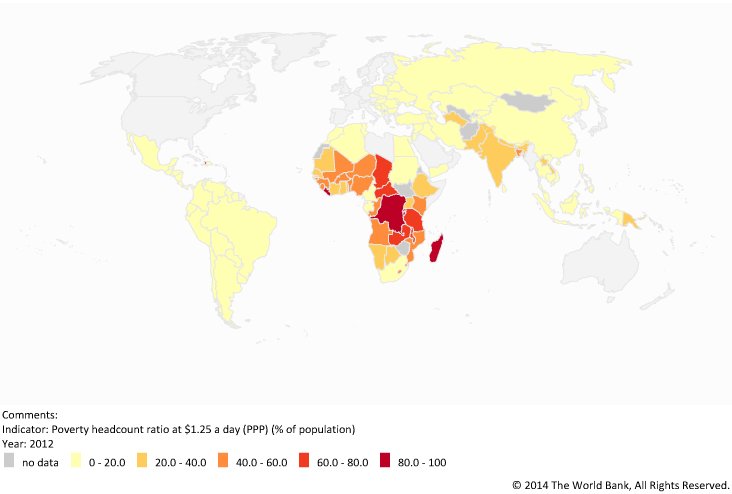

Which can be compared with the WorldBank’s interactive poverty map:

Clearly, there is a direct correlation between the two. Hence my charity, Ears To Our World, distributes not smartphones at this point, but radios.

Technological transitions can be difficult to implement. Those who live in the US may remember the recent move from analog terrestrial television to digital television. Once the announcement was made about this transition, consumers had a period of time to either upgrade televisions or buy a subsidized conversion box that helped those televisions receive the new digital signals. Many found this transition, at the very least, awkward.

But now imagine that you live in a developing country on less than one or two US dollars a day, in a village without mains power, and your news source on shortwave has suddenly been removed with only a few days notice. Your alternatives? To listen over the Internet (a service that requires a subscription you can ill afford), or pay-as-you-go access via an Internet café, a half-day’s walk away…Could you save a year’s worth of salary to help pay for an Internet-capable mobile phone that you cannot even charge locally, and then pay a monthly subscription to listen to a broadcast that used to be free over the air? It’s highly doubtful. Suddenly, this “accessible technology” seems much less accessible.

It’s easy to become complacent and assume listeners have access to broadcasting content via the Internet, when decision-makers live in a word where information is not only plentiful and ubiquitous, but even bombards us to the point that we simply tune it out.

But there are other advantages of shortwave radio over Internet–especially in parts of the world where governments tightly control their country’s media:

- Shortwave radio cannot be easily monitored by a government. In North Korea, for example, this is why shortwave radio remains a vital lifeline of information about the outside world. Censorship of shortwave radio is comparatively unsuccessful, while the Internet is often subject to total blocking.

- Shortwave radio is the ultimate free speech medium, as it has no regard for national borders, nor for whom is in power (or not in power) at any moment.

- Shortwave radio is inexpensive to the listener, because:

- Radios are affordable and plentiful;

- No apps are required, and

- No subscription fees are needed.

- Information races over shortwaves at the speed of light. No buffering is needed, and there is no speed difference between one area to another.

- Shortwave radio works everywhere on the planet. You don’t have to be within a local broadcast footprint or that of a satellite to receive broadcasts. Even in the most impoverished parts of the world, you’ll find shortwave radios and batteries that run them. Their “market penetration” surpasses even that of the smart phone.

- Shortwave radio is a basic, simple technology, requiring little to no learning curve for use.

Moreover, only this year we’ve found that shortwave radio may be an excellent means of disaster communications over vast areas, encompassing oceans and continents. Check out this report from the CDAD network.

In addition, Dr. Kim Andrew Elliott of Voice of America has been successfully broadcasting digital messages over a shortwave AM carrier for well over a year, in the form of the VOA Radiogram he produces. These data modes are so efficient, that they can break through even the most robust jamming techniques used by the Chinese government to censor broadcasts.

So, can we stop the decline shortwave radio broadcasting?

Large-scale, government-supported shortwave radio broadcasting experiences an inherent conundrum: those who fund broadcasting do not directly benefit from it. Customers pay for private broadcaster airtime, but taxpayers typically support government broadcasting.

Without the catalyst and fuel of a World War or Cold War, government-supported international broadcasting becomes invisible to those who fund it. Politicians find it easy to cut, as few constituents understand the significance of broadcasting outside their own countries. And why should they? When one lives in a first-world country with an abundance of news sources, it’s hard to relate to those who don’t.

The Canadian taxpayer spent millions of dollars to upgrade the RCI Sackville site so that it could be remotely operated; requiring only a skeleton crew on site. Sackville was closed the same year (2012) these upgrades were brought online.

I experienced this disconnect firsthand while petitioning on behalf of Radio Canada International’s Sackville, New Brunswick transmission site in 2012, in an attempt to prevent the significant site’s closure and dismantlement. Though I spoke with a number of Canadians and even members of Canadian Parliament, more often than not, I found most were not aware of Radio Canada International’s mission nor of shortwave’s relevance. Many had never heard of Radio Canada International. Even members of the public broadcasting advocacy group, Friends of the CBC, had no idea the Canadian government broadcasts to the world via shortwave radio…and that the world was listening–even relying upon–this service.

But Canada is not unique in this respect. Similar views are common here in the US, in much of Europe, and in Asia, and no doubt this lack of awareness is impacting Radio Australia at this very moment.

I’d like to think that if taxpayers knew about the real benefits of shortwave radio broadcasting to those in need, about the vital and even life-saving information broadcasters provide to vast reaches of the developing world, they would support it.

Advice to the listener

If you would like to advocate for the continuation of shortwave broadcasting, contact your local government representative and explain the benefits I’ve outlined. Use social media to spread the word. While I acknowledge that it’s something of a Don Quixote endeavor, it’s nonetheless worth making funders aware that first-world countries may one day regret the loss of this powerful form of outreach and diplomacy.

Advice to broadcasters

Considering that Big Brother can’t easily monitor shortwave radio listeners, and that shortwave radio is usually accessible to even the world’s most impoverished listeners, broadcasters can honorably defend their services to their funders. Moreover, they can use this criteria to help determine when–and where–their broadcasts are vitally needed.

If funders are feeling the pinch, broadcasters may buy time–or even a future–with the services of private broadcasters. The free market economy (and good old-fashioned sponsorship) can keep stations afloat.

But regardless, broadcasters should not dismantle their transmission sites as Canada is currently doing. Not only is the current service originating from these sites a more reliable form of emergency communications than the Internet, should a national disaster befall us; not only do they continue to provide a broad-spectrum mode of diplomacy; but should future digital communication modes find a way to take advantage of the HF spectrum as is now under discussion, this would be most unfortunate.

Imagine a wi-fi signal with a footprint as large as several countries, digital devices with tiny fractal antennas that receive this signal containing rich media (e.g., audio and video)–these are not science fiction, but highly plausible uses of these transmission sites, even within the next decade. [Update: One organization is now using shortwave to distribute their smart phone app and KNL Networks is developing shortwave-powered global Internet access.]

Government broadcasting: a quick way of finding your target audience

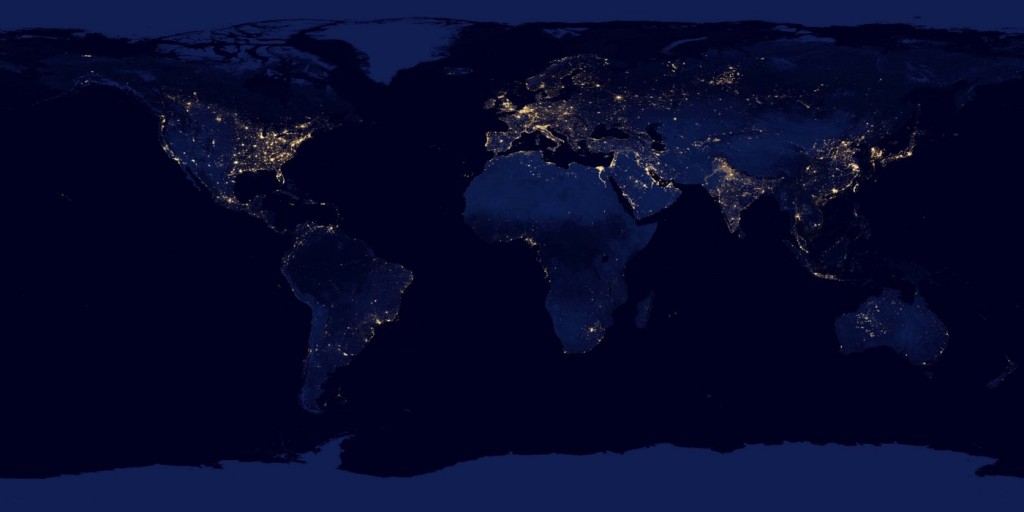

So, where does shortwave reach? Take a look at NASA’s composite map of the world at night:

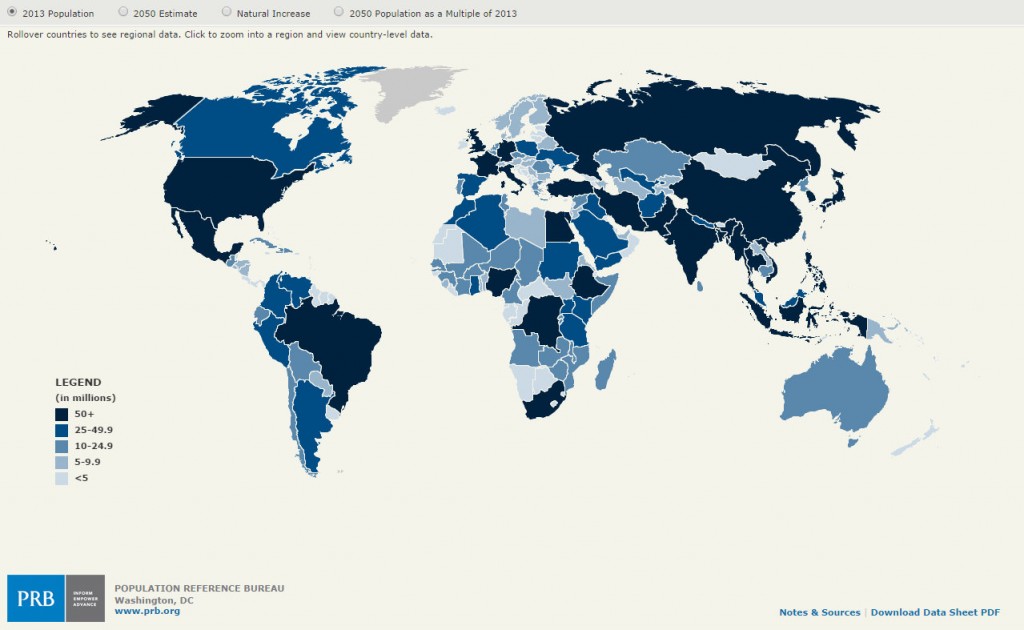

This map offers a quick view of the parts of our planet still quite literally in the dark; what’s more, it makes energy poverty shockingly apparent. Now compare this nighttime world map with the Population Reference Bureau’s most current map:

Upon comparing the two, you will be able to form a vivid picture of populated areas where most people either have no access to power, or simply can’t afford it. East Africa, west Africa, and central Africa are frankly represented. Less noticeable (at least on the NASA map) are impoverished island countries, especially in the Pacific and Caribbean; Haiti, for example, is among these.

So, let’s consider: if basic lighting is too costly for people living in the vast areas these maps indicate, what about paying for–and charging–a smartphone? Obviously, these people still rely upon other means of receiving information, which at this point is radio–primarily FM and shortwave.

Another litmus test for the greater world’s readiness to transition from shortwave radio to phone/Internet technology is as follows. Note which countries lack press freedoms, and free speech, care of the Reporters Without Border’s Press Freedom Index and Map:

This map indicates countries where those in power tightly control news and information, where the Internet is censored, and where shortwave is the only effective means of hearing the outside world. Again, you might notice the prevalence of many east African, west African, and central African countries.

We already know that shortwave radios are in common usage in these countries. But can broadcasters easily and accurately determine listener numbers in these vast, often war-torn areas? Will listeners openly admit to a survey team that they tune in to broadcasts condemned by their respective governments? Not likely. So actual listener numbers remain undetermined, although population alone provides the most useful indicator.

These listeners, kind readers, are the truly disenfranchised of our world. Still, today.

Students in South Sudan listen to their favorite shortwave radio program, VOA Learning English, with a self-powered radio supplied by Ears To Our World.

If we pull the plug on these listeners by removing shortwave radio as an information source, where will they turn? To the Internet?

Let’s assume for a moment that you’re an international broadcaster who has decided to move your content to the Internet. You campaign for and attempt to promote this transition to your listeners, some of whom are living in impoverished areas and/or under repressive regimes (these frequently go hand-in-hand). Do you really think these people can: 1) Afford an Internet service and Internet capable device? 2) Surf anonymously with no chance of their government knowing about the content they research? 3) Ensure that their Internet sources aren’t filtered by their government? 4) Feel confident that their Internet source won’t be turned off at a moment’s notice–?

And none of these points is a stretch. China is the world’s most populous country; it teems with humanity–19% of all of us on this planet live in China. China has excellent Internet penetration…as well as a government that tightly controls and filters this content. I’ve even experienced this firsthand, upon posting an article about China’s Firedrake jamming service which attempts (with only moderate success) to limit shortwave radio in China; within 12 hours, my website received a denial-of-service attack originating in, of course, China. It crippled our website for 24 hours. We had to filter the IP addresses causing the attack, which effectively made it difficult for readers in China to view our site. (China, is regarded as the sixth worst country in terms of press freedoms, according to the Press Freedoms Index). Shortwave can sidestep jamming much more effectively than the Internet can ever hope to overcome such vicious service attacks.

Meanwhile, in Africa…During the last election cycle in Zimbabwe, as some readers may be aware, Robert Mugabe ordered the confiscation of shortwave radios throughout the country. He clearly feared outside news sources like the Voice of America, BBC World Service, and the now-defunct SW Radio Africa. If there was no audience for this information, would Mugabe have gone to such lengths? According to the World Bank, only about 17% of the population of Zimbabwe has access to the Internet (and if you expect this 17% is uniform according to income, you’d be mistaken). The disenfranchised in Zimbabwe, by and large, do not have free and open access to the Internet.

A (modest) positive spin on the decline of shortwave broadcasting

Writing this article has been a cathartic experience for me. In this article, I’ve focused more on the negative implications of shortwave radio’s decline, especially within the humanitarian context. The decline of shortwave radio is a fact I don’t like to face, yet it’s in front of me every day as a humanitarian and as a listener.

But somehow, I’m still an optimist. While others are loudly complaining there’s nothing to listen to on the bands, I’ll be quietly listening to those stations that they don’t realize still exist.

Even as I wrote this column, I was listening to Alcaravan Radio in the wee hours of the morning. Mambo music emanated from Alcaravan’s low-power (1,000 watt) Columbian station. It amazes me that this relatively weak signal punches through the ether during the night and fills my headphones with music. This little signal, and many others like it, play on in the pale glow of shortwave’s apparent “sundowning,” and somehow, this decline is mocked by the cheerful sound.

There are numerous small stations out there like Alcaravan Radio, more than most uninitiated listeners would ever believe. To be clear, though, I would not be able to hear Alcaravan Radio so well if it wasn’t for the fact that I have a good receiver hooked up to a decent wire antenna, and I live in a rural, RFI-free area. I can understand that those living in urban areas with a lot of local noise may get frustrated with the lack of stations to be heard from a portable radio, just as urban light pollution makes it nearly impossible for amateur astronomers to experience the kind of star-gazing their rural friends enjoy. With low RFI, the world opens up on the shortwave bands.

The truth is, I actually do more SWLing now than I did back when the bands were crowded. Why? The challenge has become less about hearing an elusive station through adjacent signal interference, and more about finding those DX stations buried in the static–or waiting for a propagation opening to snag something truly special. With less stations on the air, there is less interference to obscure weaker stations.

As my buddy Dave Richards (AA7EE) recently wrote:

“[T]he silver lining to the cloud is that the new shortwave landscape encourages solely English-speaking listeners to listen outside their immediate comfort zones by listening to broadcasts in other languages. [T]he absence of some of the previously bigger signals makes it a little easier to spot the weak rarities.”

I also enjoy listening to the thriving free radio (aka, pirate radio) scene. Unlike big government broadcasting, this micro-broadcasting is ever changing, growing, and becoming more innovative. (Check out the pirate radio listening primer published earlier this year.)

Yes, variety is still there. For proof, check out some of the recent recordings posted on the Shortwave Radio Audio Archive. In the past year, I’ve personally recorded hundreds of international broadcasters, pirate radio stations, utility stations, and even numbers stations; this doesn’t even include the many more I’ve logged. And, yes–I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it.

Long Live Shortwave

If you feel so compelled, be an advocate for shortwave radio; it’s something you can do for those who don’t have a voice in this matter. Contact your local representative, and ask him/her to maintain vital transmission sites and world broadcasts. Your voice can make a difference here–and across the planet, too.

And in the meanwhile, regarding the much-talked-of coming demise of shortwave, don’t be discouraged by the naysayers and doomsdayers. Join me in contributing to the Shortwave Archive and the SWLing Post. After all, there’s still much to be heard on the shortwaves. How? Simply by listening.