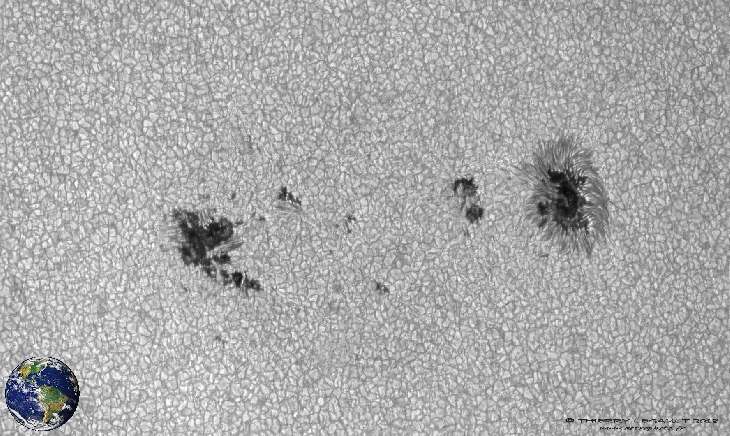

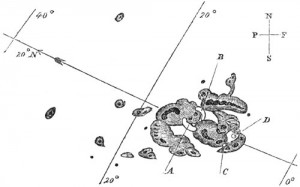

Sunspots of September 1, 1859, as sketched by Richard Carrington A and B mark the initial positions of an intensely bright event, which moved over the course of 5 minutes to C and D before disappearing. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

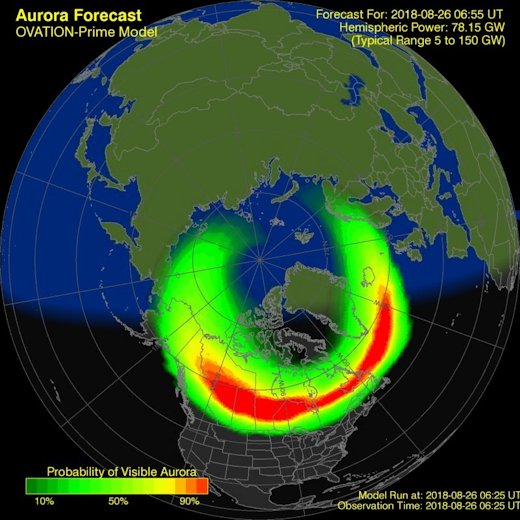

These days, CMEs and solar flares get a great deal of media attention. But it’s mostly speculation–for even with our advanced abilities to measure the potential impact, we can’t be sure what will happen each time this occurs. Might this solar flare be strong enough to damage our satellites and electrical infrastructure? we may wonder. Could it ‘fry’ our electrical grid?

The concerns are merely speculative. But is there actual cause for concern? Surely. A massive solar flare could damage much of our technology in space–such as our satellites–and could also certainly cause headaches for those who manage our electrical grids.

But do we know how powerful solar events can be? History may hold the answer.

In September of 1859, a solar flare was so massive that there were newspaper reports of it across the globe, and many found the strange light it created baffling. Of course, now, there’s no speculation as to what happened then–eyewitness accounts and plenty of written evidence in this pre-internet era paint a clear picture of a massive coronal ejection. This event has been referenced many times as a benchmark–one that, should it happen now, would certainly give us serious pause. Technologically, that is.

I happened upon a fantastic article about the 1859 flare on ARS Technica called: 1859’s “Great Auroral Storm”—the week the Sun touched the earth.

The following is an excerpt:

It hit quickly. Twelve hours after Carrington’s discovery and a continent away, “We were high up on the Rocky Mountains sleeping in the open air,” wrote a correspondent to the Rocky Mountain News. “A little after midnight we were awakened by the auroral light, so bright that one could easily read common print.” As the sky brightened further, some of the party began making breakfast on the mistaken assumption that dawn had arrived.

Across the United States and Europe, telegraph operators struggled to keep service going as the electromagnetic gusts enveloped the globe. In 1859, the US telegraph system was about 20 years old, and Cyrus Field had just built his transatlantic cable from Newfoundland to Ireland, which would not succeed in transmitting messages until after the American Civil War.

“Never in my experience of fifteen years in working telegraph lines have I witnessed anything like the extraordinary effect of the Aurora Borealis between Quebec and Farther Point last night,” wrote one telegraph manager to the Rochester Union & Advertiser on August 30:

The line was in most perfect order, and well skilled operators worked incessantly from 8 o’clock last evening till one this morning to get over in an intelligible form four hundred words of the report per steamer Indian for the Associated Press, and at the latter hour so completely were the wires under the influence of the Aurora Borealis that it was found utterly impossible to communicate between the telegraph stations, and the line had to be closed.

But if the following newspaper transcript of a telegraph operator exchange between Portland and Boston is to be believed, some plucky telegraphers improvised, letting the storm do the work that their disrupted batteries couldn’t:

Boston operator, (to Portland operator) – “Please cut off your battery entirely from the line for fifteen minutes.”

Portland operator: “Will do so. It is now disconnected.”

Boston: “Mine is disconnected, and we are working with the auroral current. How do you receive my writing?”

Portland: “Better than with our batteries on. Current comes and goes gradually.”

Boston: “My current is very strong at times, and we can work better without the batteries, as the Aurora seems to neutralize and augment our batteries alternately, making current too strong at times for our relay magnets.

Suppose we work without batteries while we are affected by this trouble.”

Portland: “Very well. Shall I go ahead with business?”

Boston: “Yes. Go ahead.”

Telegraphers around the US reported similar experiences. “The wire was then worked for about two hours without the usual batteries on the auroral current, working better than with the batteries connected,” said the Washington Daily National Intelligencer. “Who now will dispute the theory that the Aurora Borealis is caused by electricity?” asked the Washington Evening Star.

Read the full and fascinating article, 1859’s “Great Auroral Storm”—the week the Sun touched the earth on arstechnica.