Radio Waves: Stories Making Waves in the World of Radio

Because I keep my ear to the waves, as well as receive many tips from others who do the same, I find myself privy to radio-related stories that might interest SWLing Post readers. To that end: Welcome to the SWLing Post’s Radio Waves, a collection of links to interesting stories making waves in the world of radio. Enjoy!

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributors, Mike Terry, Troy Riedel, andGrant Porter for the following tips:

WBCN history reveals revolutionary power in local radio (Boston University News Service)

SOMERVILLE – What started as a midnight to 6 a.m. slot on a failing classical music station, became the voice of a generation in 1970s Boston. Now, more than 50 years after WBCN sparked a “revolutionary new experiment in radio,” the bygone rock station is still making waves.

The 2018 documentary, “WBCN and The American Revolution,” tells the origin story of Boston’s first rock and roll station through a combination of rock hits. Never-before-seen photos, videos and interviews with some of Boston’s most beloved radio hosts, were greeted with cheers at the Somerville Theatre screening Thursday night.

Bill Lichtenstein, who began volunteering with WBCN at 14, directed and produced the film. After crowdfunding and a decade in the making, it has been touring independent theaters and festivals across the U.S. for the last year and a half.

WBCN was grounded in good music. Founded by Ray Riepen, owner of South End music venue The Boston Tea Party, WBCN introduced voices like The Velvet Underground, The Who, Bruce Springsteen and Led Zeppelin to the city, and quickly found a home in Boston’s huge student population. Within three months, the station, run by amateur hosts and young volunteers during classroom breaks, was playing 24 hours per day.[…]

“It Will Make Millions of Receivers Obsolete … This Is Needless” (Radio World)

What people are saying to the FCC about all-digital on the AM band

Radio World is providing an ongoing sampler of comments of what people are telling the FCC about its proposal to allow U.S. stations on the AM band to switch voluntarily to all-digital transmission. Here are more in the series:

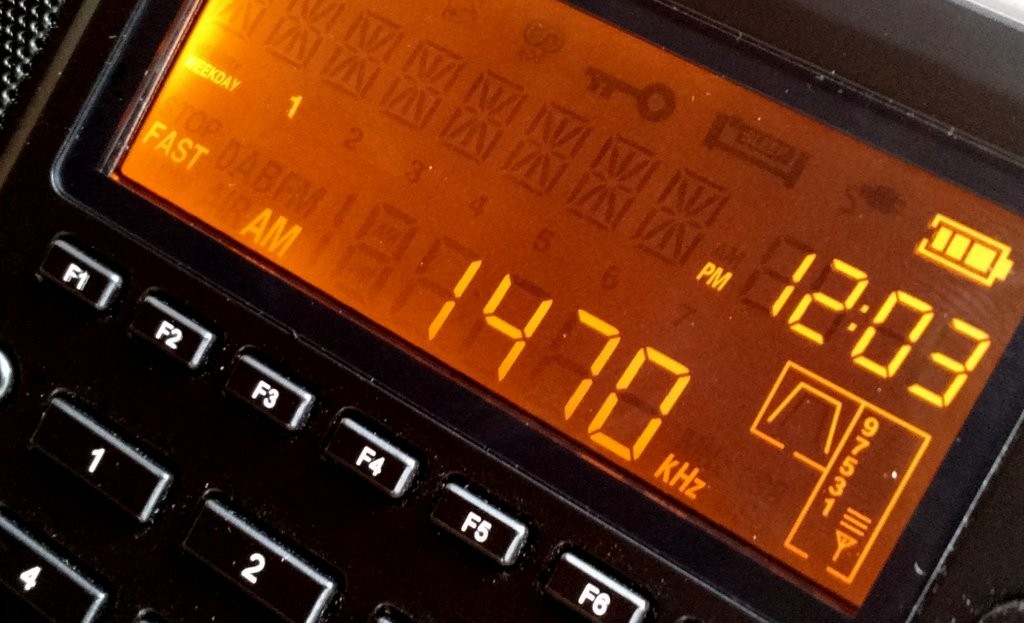

Kirk Mazurek told the FCC that he is an avid AM listener who has “invested time and money in equipment towards my hobby as many others have. If this proposal goes through it will make the millions of receivers obsolete requiring the purchase of new equipment. This is needless, there are a lot of people who have vintage radios and a lot of them have been restored. This proposal would make them useless. I urge you not to ratify this proposal.”

Mark Wells raised concern about interference from digital to analog signals on the same channel. “This is especially applicable at night when one is listening to distant stations in out-of-state markets, he wrote. “For example, clear channel stations WBT in Charlotte and KFAB in Omaha are both on both on 1110 kHz. Let’s say one switches to digital, and one does not. As it is they both may fade in and out as the atmosphere does its nightly tricks, but the signals remain mostly useable. But, if one is digital and the other analog would it not ‘blank out’ the analog station?”[…]

Podcast features Coastal Radio Station KPH (DitDit.fm)

There was a time when the airways bristled with Morse Code. There were commercial radio stations all around the world whose business was sending and receiving Morse Code messages to ships at sea. Coast station KPH, located at Point Reyes National Seashore near San Francisco, is one of those stations. Richard Dillman was there in 1997 when KPH sent it’s last message and closed it’s doors. It was the end of the line for the men and women who had spent their careers sending Morse Code to ships at sea. There was nowhere else for them to go…

Two years later, Richard Dillman with a group of volunteers returned to KPH and put it back on the air. Listen as Richard tells us about the future of Maritime Morse Code Coastal Station KPH!

A hydrogen line telescope made from cereal boxes and an RTL-SDR (RTL-SDR.com)

SpaceAustralia.com have recently been hosting a community science project that involves encouraging teams to build backyard radio telescopes that can detect the arms of our Milky Way Galaxy by receiving the Hydrogen line frequency of 1420 MHz.

This can be achieved at home by building a horn antenna out of cardboard and aluminum foil, and a feed from a tin can. Then the Hydrogen line and galactic plane can be detected by using an RTL-SDR, LNA, and software capable of averaging an FFT spectrum over a long period of time.

While most horn antennas are typically made from four walls, one participant, Vanessa Chapman, has shown that even trash can be used to observe the galaxy. Vanessa’s horn antenna is made from multiple cereal boxes lined with aluminum foil and an old tin fuel can. The boxes are held together by some string and propped up by some sticks.

With her cereal box horn antenna combined with an RTL-SDR Blog V3, and an RTL-SDR Blog Wideband LNA, Vanessa was able to use software to average the spectrum over time as the galactic plane passed overhead, revealing the Hydrogen line peak and corresponding doppler shift from the galactic plane.[…]

Do you enjoy the SWLing Post?

Please consider supporting us via Patreon or our Coffee Fund!

Your support makes articles like this one possible. Thank you!