By Jock Elliott, KB2GOM

When you live in an antenna-challenged situation as I do (stringing long wire antennas outside is problematic for me), the result is a never-ending search for an improved signal.

Toward that end, I’ve experimented with a horizontal room loop, an indoor end-fed, and a short dipole.

Along the way, I decided to test the MFJ 1020C active antenna/preselector, and I liked it pretty well. My conclusion was: Bearing in mind that it won’t improve every signal you want to hear, if you live in an antenna-challenged situation, the MFJ 1020C – particularly if you can get 20-50 feet of wire outdoors or run around the perimeter of a room – may be just what the doctor ordered.

After my test of the 1020C, I had an online conversation with Andrew (grayhat), and he suggested that I might want to have a look at the MFJ 956 passive selector. Its major claim to fame is: “Boost your favorite stations while rejecting images, intermod, and phantom signals! The MFJ-956 Pre-Selector/Antenna Tuner greatly improves reception from .15 to 30 MHz — especially below 2MHz. It has tuner bypass/ground receiver positions. The MFJ-956 measures a compact 2 x 3 x 4 inches.”

MFJ was kind enough to send a 956 to me, and while I did not test it below 2 MHz, I found that it proved very helpful in tuning in the BBC mid-winter broadcast to Antarctica. I started out with the MFJ 1020C. Lots of noise and fades. Reception was somewhat better using the 1020C (compared to bypass), but then I switched to MFJ 956. I found I could copy better with the 956, even though it provides no amplification. Tuning slightly off-peak offered the best copy, better than bypass. I was listening in USB. In all, it is a useful piece of gear.

While poking around the MFJ website I discovered the MFJ 1046 Receiver Preselector, 1.6-33 MHz. Among other claims, MFJ has this to say about the 1046: “MFJs new Passive Preselector has extremely high dynamic range! It improves the performance of nearly any HF or shortwave receiver/transceiver. It vastly improves the most expensive receivers. Especially helpful to those with broadband front-ends that are prone to overload.”

Sounds promising, I thought, so I emailed Thomas, SWLing’s Maximum Leader, to see if maybe MFJ would like me to have a look at one.

A happy accident

A few days later, package arrived.

I was unpacking it when the Brain Dudes interrupted.

Brain Dudes: Hey!!

Me: What?!!

Brain Dudes: That thing look a little weird to you?

Me: Whaddya mean?

Brain Dudes: Look at the front . . . what do you see?

Me: Well, on left, a knob labeled GAIN; next to that, and ON/OFF button; moving to the right, a BAND selector switch, and finally a TUNE knob.

Brain Dudes: And what is the MFJ 1046 supposed to have?

Me: A big tuning knob, an ON/OFF switch, and a BAND selector switch . . . maybe this is an improved model . . .

Brain Dudes: How ‘bout you look on the back panel . . . what do you see?

Me: The usual connections for antenna and receiver . . . and a plug-in socket for an external power supply.

Brain Dudes: Is a passive preselector supposed to have a power socket?

Me: No . . .

Brain Dudes: OK, final clue, Sherlock: suppose you read the label on the front panel.

Me: MFJ 1045C. Holy smokes! They sent me the wrong unit!

(I hear the Brain Dude yelling at someone in the background: “Finally, the light comes on! I told you switching to decaf was a bad idea!)

Brain dudes: So they sent you the wrong unit; suppose you test it anyway since it’s here.

So I did. And it turns out that MFJ sending the 1045C instead of the 1046 was a happy accident because the 1045C, which is an active preselector, delivers excellent performance across the board.

This is what MFJ says about the 1045C: “Lets you copy weak signals. Rejects out-of-band signals, images. 1.8 to 54 MHz. Up to 20 dB gain. Gain control. Dual gate MOSFET, bipolar transistors for low noise, high gain. Connect 2 antennas, 2 receivers. Coax and phone jacks. 9-18 VDC or MFJ-1312D.”

Once the antenna, receiver, and power supply are connected (I used the power supply that MFJ sent me with the 1020C), I operate the 1045C in much the same way as the 1020C:

- With the unit in BYPASS mode (the ON/OFF button out), tune the receiver to the frequency you want to hear.

- Set the GAIN knob to around 3 or 4.

- Set the BAND knob to the band with the MHz that you are tuned to.

- Press the ON/OFF/BYPASS button in. This turns on the active preselector and amplification circuits and a red light comes on to let you know the unit is activated.

- Slowly turn the TUNE knob back & forth. At some point in its tuning range, you will hear the signal and/or noise peak.

- Finally, adjust the GAIN knob for maximum intelligibility of the signal. Sometimes tuning slightly to the side of the peak works best.

I tested the MFJ 1045C with my end-fed indoor antenna (see link above) and with the short dipole (also, see link above). I also did head-to-head comparisons with the MFJ 1020C and those two antennas.

The results

Here’s what I found:

- The indoor end-fed antenna (which is 45 long) out-performs the short dipole (which is 6 feet total length) in all cases. That’s no surprise, but bear in mind that not everyone has a situation in which they can deploy the longer antenna. The 6-foot dipole definitely out-performs the whip antenna on my Satellit 800.

- The 1045C has a broader range of amplification than the 1020C. It appears to reject adjacent channel interference as well or better than the 1020C, and, to my ear, the 1045C has a lower noise floor. If you turn the GAIN knob fully to the left, it gets to a position where it appears to actually attenuate the signal. And I never found a situation in which, if properly tuned, the signal delivered by the 1045C was at least equal to the bypass signal, and many times it was significantly better. In short, in the HF range the 1045C appears do to everything that the 1020C does (with the exception of the 1020C’s screw-in whip antenna) and do it better.

- When using the 1045C with a portable (my Tecsun 880), I found that I could hear the noise peaks better than with the 1020C, which is a great help in tuning for best performance.

So why would you chose the 1020C or the 956 over the 1045C? Short answer: if you are a MW or LW enthusiast. According to MFJ, the 1045C covers 1.8 to 54 MHz; the 1020C covers .3 to 40 MHz, and the 956 covers 150 kHz to 35 MHz.

However, if you are an HF weenie like I am who enjoys teasing out faint signals, and particularly if you are faced with a sub-optimal antenna situation, the MFJ 1045C, in my opinion, is definitely worth a try.

Click here to check out the MFJ-1045C.

Shameless plug: check out the SWLing Post Message Board there are often interesting discussions going on there.

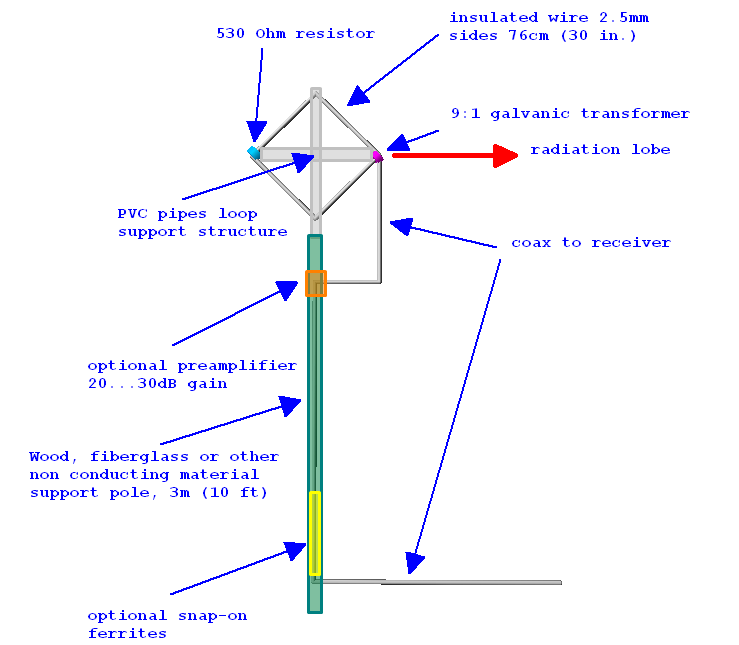

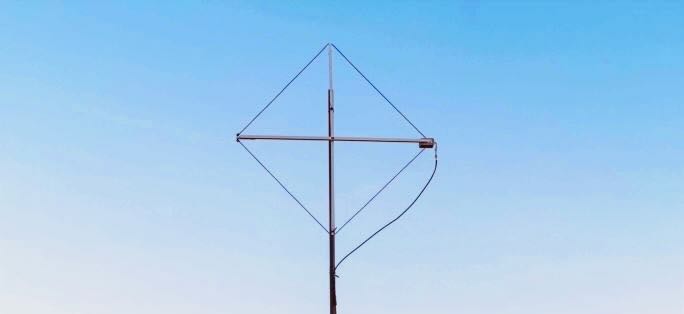

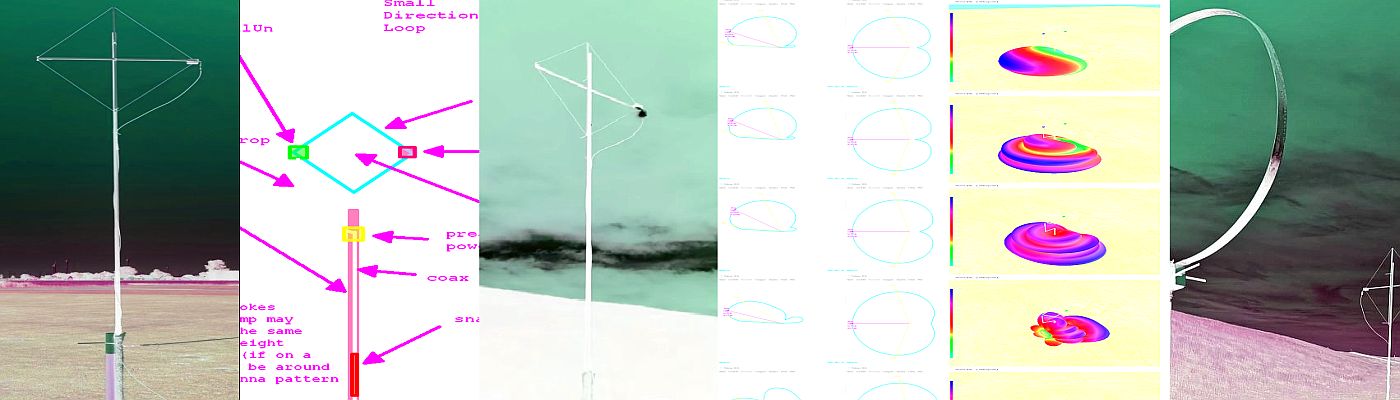

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor extraordinaire, 13dka, who brings us Part Two of a three part series about the new SULA homebrew antenna project. This first article describes this affordable antenna and demonstrates its unique reception properties. This second article focuses on construction notes. The third and final article will essentially be a Q&A about the SULA antenna. All articles will eventually link to each other once published.

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor extraordinaire, 13dka, who brings us Part Two of a three part series about the new SULA homebrew antenna project. This first article describes this affordable antenna and demonstrates its unique reception properties. This second article focuses on construction notes. The third and final article will essentially be a Q&A about the SULA antenna. All articles will eventually link to each other once published.