Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Jock Elliott, who shares the following guest post:

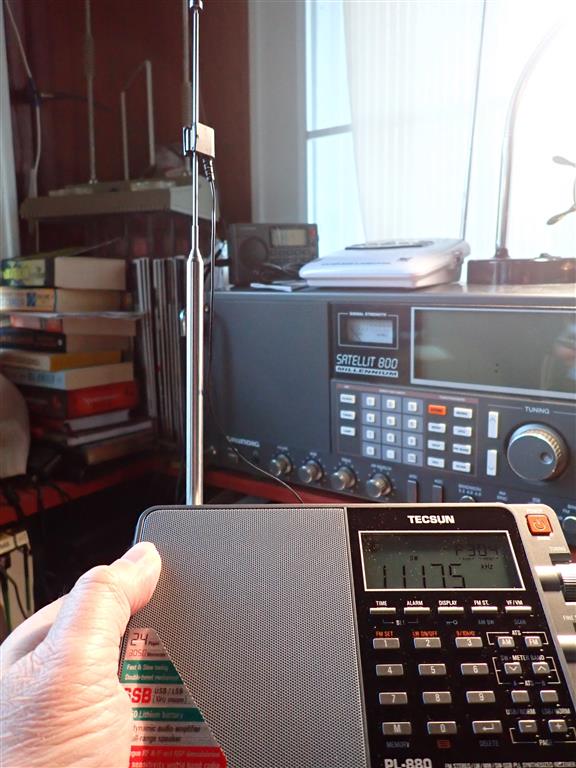

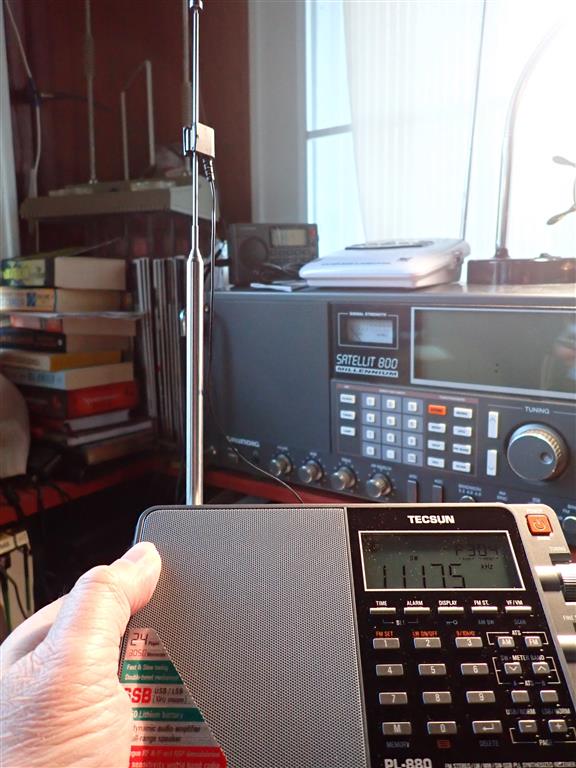

The Satellit 800, the Tecsun PL-880, and two indoor antennas – an afternoon of experimentation

By Jock Elliott, KB2GOM

A search for “shortwave listening antennas” on the internet landed me on the page for the Par EndFedz® EF-SWL receive antenna, which is a 45-foot end-fed wire antenna connected to a wideband 9:1 transformer wound on a “binocular core” inside a UV-resistant box. A link on the page invited me to check out the eHam reviews of this antenna, which are here. What struck me is that there are just page after page of 5 star reviews of this antenna. Hams and SWLs apparently just love it. (If you want to buy of these antennas, they are now sold by Vibroplex and can be found here.)

As I reached for my credit card, I remember that I had an LDG 9:1 unun transformer lying around and some wire left over from the Horizontal Room Loop project. Maybe I could create my own end-fed SWL antenna by wrapping the wire around the perimeter of the room, attaching it to the 9:1 unun and then by coax to the back of my Grundig Satellit 800.

So I did exactly that. The wire for new end-fed antenna travels the same route around the perimeter of the room as the horizontal room loop. The main differences between the two antennas are that the end-fed is not a loop, and it terminates in the 9:1 transformer, which, in turn, feeds the Satellit though a coax cable. But in essence, we’re talking about two indoor wire antennas that are the same length and laid out along the same path about 7 feet in the air around the interior of the 8-foot by 12-foot room that serves as a library and radio shack: the horizontal room loop and the indoor end-fed.

The Satellit 800 has three possible antenna inputs: the very tall built-in whip antenna, two clips on the back of the 800 where the horizontal room loop attaches, and a pl-239 coax connector where the new end-fed antenna attaches. In addition, there is a three-position switch that allows me to quickly switch from one antenna to another.

Tuning up on the WWV time stations on 5, 10, 15, and 20 MHz and sliding the switch on the back of the Satellit 800 among the three different positions, I quickly found that the whip antenna was the noisiest of the three choices and offered the poorest signal-to-noise ratio. The comparison between the horizontal room loop and the indoor end-fed antenna was very, very close. While the horizontal room loop was quieter, it seemed to me that the signal offered by the indoor end-fed antenna was the tiniest bit easier to hear, so I decided to leave the Satellit 800 hooked up to the indoor end-fed antenna.

The 100-foot indoor end-fed antenna

Then I did something I had wanted to do for quite a while: I disconnected the horizontal room loop from the back of the Satellit 800 and attached one end of the wire to the indoor end-fed. So now, I had a roughly 100-foot end-fed antenna wrapped twice around the room.

Before we proceed any further, you need to understand this: my comprehension of antenna theory is essentially nil. As the old-timers would have it: you could take the entirety of what I understand about antenna theory, put it in a thimble, and it would rattle like a BB in a boxcar.

Ever since the successful creation of the horizontal room loop, I had wondered: if 50 feet of wire wrapped around a room improves the signal, would 100-feet of wire improve the signal even more? Inquiries to several knowledgeable people produced the same result: they didn’t think so.

Guess what? They were right . . . entirely and completely right. Tuning to the time stations and attaching and detaching the extra 50 feet of wire from the indoor end-fed, I saw (on the signal strength meter) and heard no difference in signal strength or signal-to-noise ratio.

The PL-880 and Satellit 800 comparison

So now, the Satellit 800 is attached to the indoor end-fed antenna, and there is an extra 50 feet wire wrapped around the room on the same path as the end-fed. Wouldn’t it be nice if I could find a way to hook that extra wire up to my Tecsun PL-880?

An old auxiliary wind-up wire antenna from a FreePlay radio came to the rescue. It was an annoying piece of gear; the wire was difficult to deploy and even more difficult to wind up again, and it had languished in a drawer for more than a decade. But it had a really nifty clip on the end that was designed to easily snap on and off a whip antenna.

Pulling an arm-spread of wire out of the reel, I cut it off, stripped the wire, attached it to the end of what had been the horizontal room loop, and clipped it to the whip on the PL-880. Tah-dah . . . instant improvement to the signal coming into the PL-880.

Some time ago, a reader had asked whether I found the Satellit 800 a little deaf in comparison to the Tecsun PL-880. Now, with two indoor antennas of approximately the same length and routed along the same path, I could do the comparison on shortwave frequencies. Starting with the time stations and later with hams in single-sideband on the 20-meter band, I alternated between the two radios. Although the PL-880 has more bandwidth choices, and the two radios have a slightly different sound to them (probably, I’m guessing, due to differences in their circuitry), the bottom line is this: anything I could hear with the Satellit 800 I could also hear with the PL-800 . . . and vice versa. (Note: I did not do any comparison between the two on medium wave or FM.)

In my not-so-humble opinion, both offer worthy performance that is improved with the addition of a 50-foot wire antenna, even if it is indoors.

And that brings us to the final point.

A word of caution

If you decide to add a bit of wire to improve the signal coming into your shortwave portable or desktop receiver, do NOT, under any circumstances, EVER deploy the wire where it could come into contact with a powerline or fall onto a power line or where a power line could fall on it.

As Frank P. Hughes, VE3DQB, neatly put it in his wonderful little book Limited Space Shortwave Antenna Solutions: “Make sure no part of any antenna, its support or guy wires can touch a power line before, after, or during construction. This is a matter of life and death!”

And when thunder and lightning threaten, make sure your outdoor antenna is disconnected and grounded.

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Jock Elliott, who shares the following guest post:

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Jock Elliott, who shares the following guest post: