Radio Waves: Stories Making Waves in the World of Radio

Welcome to the SWLing Post’s Radio Waves, a collection of links to interesting stories making waves in the world of radio. Enjoy!

Many thanks to Dennis Dura for many of these tips!

The new year was bittersweet for many Bengali radio fans this year, as listeners learned that BBC Bangla Radio would stop airing on December 31, 2022, after an 81-year run. In the years leading up to its closure, two sets of half-hour programs were aired each day on shortwave and FM bands in the morning and evening. The webpage was archived as soon as the night programs finished on the last day, closing the chapter on the iconic British Broadcasting Channel segment.

In an effort to cut spending and follow media trends, BBC World Service will be pivoting toward increased digital offerings, leading them to shut down radio-wave broadcasts in several international languages. BBC Bangla will continue as a digital-only multimedia channel in a limited capacity.

Bangla (Bengali) is the seventh most spoken language by the total number of speakers in the world. Spoken by approximately 261 million worldwide, it is the primary language in the region of Bengal, comprising Bangladesh (61 percent of speakers) and the Indian state of West Bengal (37 percent of speakers). [Continue reading…]

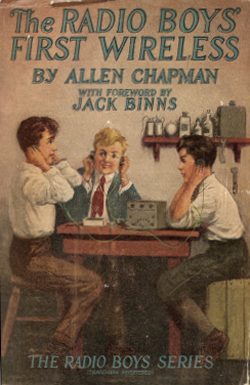

A new book from Standard Manual

A trove of more than 150 such QSL cards, formerly owned by an operator who went by the call sign W2RP, was obtained by designer Roger Bova. Bova then collaborated with the book imprint Standards Manual (full disclosure: I’ve done some work with the publisher’s parent company, the design firm Order) to collect them into a handsome volume. I’m reprinting some of the images here, with the publisher’s permission.

W2RP, as it turns out, was no ordinary “amateur.” W2RP was the late Charles Hellman, who lived to the age of 106. The cards obtained by Bova are both a visual map and a physical manifestation of the numerous conversations he participated in over what is said to have likely been the longest continuously active ham license, more than 90 years. Hellman first obtained his license at the age of 15. Some historical context: he was born in 1910, one year after the Nobel Prize in Physics went to Guglielmo Marconi and Karl Ferdinand Braun for their pioneering work in radio. Hellman himself taught physics in Manhattan and the Bronx, and two of his students reportedly went on to win the Nobel in physics. (More on his remarkable life at qcwa.org.) [Continue reading…]

Click here to read more about the book at the publisher’s website.

‘It would be the understatement of the year to say there were a lot of radios and radio-related paraphernalia’ at Chevy Halladay’s Orillia home

As I crossed the porch toward the side door of Chevy Halladay’s century home near Orillia, I had no idea what to expect. The door opened before I could knock, Chevy extended his arm to shake hands, and welcomed me into his home.

To my right was a small closet where I could hang my coat. I missed the hook, sending the coat to the floor. I was much too distracted to waste another second on hanging it neatly. To my left was a huge, free-standing mid-50s radio and TV tube testing machine stacked high with rare tubes, a six-foot-tall floor clock and radio with a built-in turntable, and a vintage Coca Cola vending machine. Each piece had been carefully restored for appearance and functionality.

A single step further into the room brought Chevy’s, and his wife Maggie’s, kitchen counter into view. Atop it were two partially restored radios, one a jumble of dusty tubes and a speaker early into the process, the other a spectacular and rare wood-cased Stromberg-Carlson, being prepared for final refinishing before being shipped to a friend in Bethesda, Maryland.

Don’t misunderstand. This was no hoarder’s enclave or home transformed into a ramshackle workshop. Their house is immaculate, and Maggie is on-side with Chevy’s mono-themed interior decorating style, yet it would be the understatement of the year to say there were a lot of radios and radio-related paraphernalia everywhere.

There was not an inch of wall that wasn’t shelved to display countless historic radios, or covered with hanging wall clocks that were used as promotional items by radio companies, steel promotional signs, framed advertising posters, or other memorabilia. [Continue reading…]

Between 1970 and 1991 a woman, never named and with a sonorous antipodean accent, could be heard broadcasting some of the most extraordinary communist propaganda ever heard amongst the radio stations of the former socialist countries.

Radio Tirana broadcast from Albania – at one time Europe’s most secretive and closed country.

The transmissions were the source of enormous fascination for one 13 year old boy who listened to the programmes at bath time, with increasing amazement.

53 year old journalist John Escolme was that 13 year old.

We join his journey to track down the mystery broadcaster who not only recalls her life on-air, but her own extraordinary personal story – one that took her from remote New Zealand to an eccentric Stalinist regime rarely visited by anyone from the west. [Click here for original article.]

Do you enjoy the SWLing Post?

Please consider supporting us via Patreon or our Coffee Fund!

Your support makes articles like this one possible. Thank you!