A Selected History of Receiver Innovations Over the Last 100 Years

by Brad Brannon

This article, the first of a two-part series on receiver technology, looks at the genesis and early advances of this all-important area.

Many contributed to the early days of wireless, but it’s safe to say that Guglielmo Marconi ranks as one of the more prominent. While known for his wireless technology, many people are less familiar with the business he created around wireless technology at the turn of the 19th century. For about 20 years after the start of the 1900s, he built a critical business that launched the world of wireless toward what we have today.

His commercialized technology was not the most up-to-date. However, it was good enough despite rapid technological changes because he figured out how to use the technology available to him to enable a new industry.

Marconi set out to deploy a worldwide network capable of sending and relaying messages wirelessly at a time when the world was in turmoil at the end of colonialism, mainly due to the wars and disasters that pockmarked the start of the 1900s, including the sinking of the RMS Titanic in April of 1912. The role that wireless played in both the rescue of survivors and the dissemination of the news of that accident reinforced the importance of this fledgling technology.

The key role that wireless technology could play wasn’t missed by either the public or the military, notably Joseph Daniels, who later became the secretary of the U.S. Navy. In the U.S. and elsewhere, leaders such as Daniels felt that the military should nationalize radio to ensure that they had access to it during wartime. It must be kept in mind that during this period, the only usable spectrum was below 200 kHz or so. At least for a while, things moved in this direction. After World War I, the government’s control of wireless weakened, but not before the formation of the government-sanctioned monopoly that created the Radio Corporation of America (RCA).1

The Early Radio Days

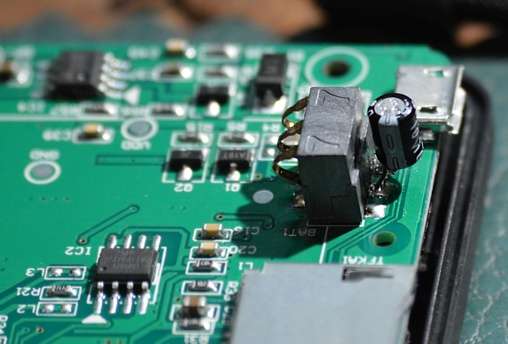

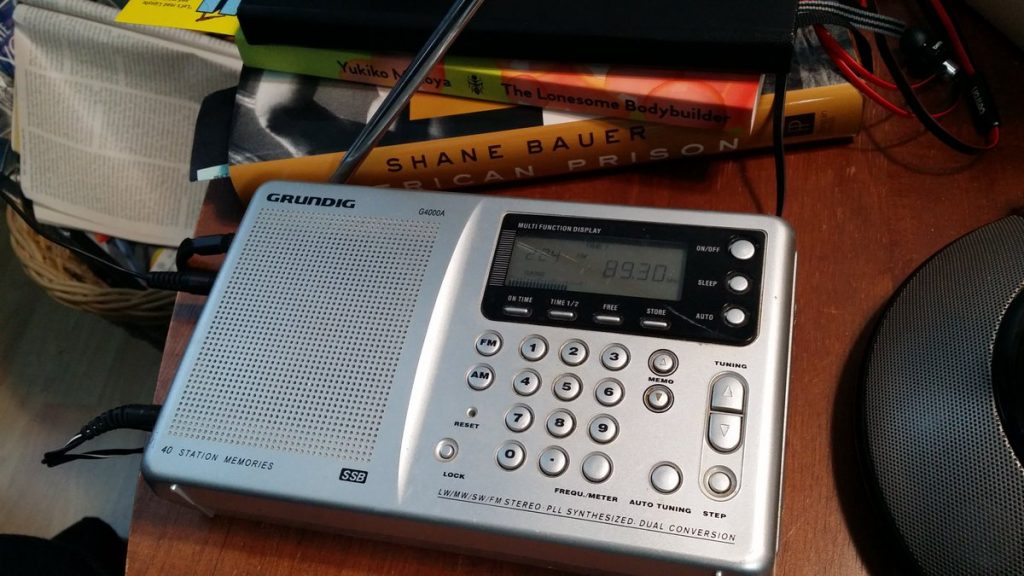

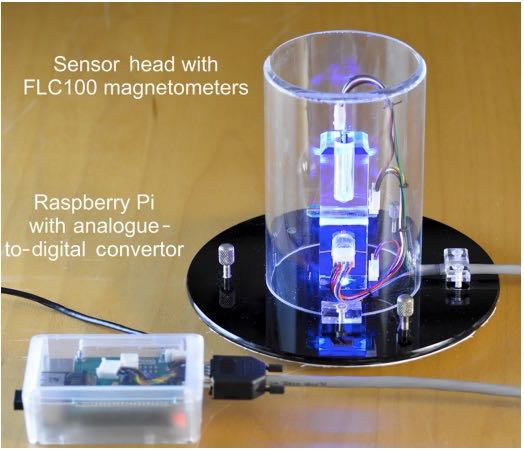

By our expectations, the radios of Marconi’s time were quite primitive. The transmitters employed spark-gap devices (only later did they employ mechanical alternators) to generate the RF. But on the receiving end, the systems were fully passive and consisted of an antenna, resonant LC tuner, and some sort of detector. These detectors will be covered shortly, but they were either mechanical, chemical, or organic.

Some of these systems employed a battery simply to bias them, but not to provide any circuit gain as we might recognize today. The output from these systems was supplied to some sort of headset to convert the signal to audio, which was always very weak and just a simple click or buzz at best.

Because these systems provided no gain on the receiving end, range was determined by the amount of transmitted power, the quality of the receiver, the experience of the operator to adjust it, and, of course, atmospheric conditions. What Marconi realized was that given a reasonably predictable range, a network of stations could be built to reliably communicate information across both continents and oceans. This included installations both on land and at sea.

Marconi set off to install his wireless stations across the globe and at sea, both on passenger ships and cargo ships.[…]