FastRadioBurst 23 letting you know of a forthcoming project from DJ Frederick called The Radio Enthusiast e-APA. It looks very interesting and will cover subjects we all love radio-wise! As the flyer above states the main purpose of the project is “for fun, to connect with other radio enthusiasts, to share information & creativity.” It’ll be available via email and a print edition and also a possible audio program. It will go out three times a year: Spring, Summer and Autumn starting Summer 2024. So please send you submissions to: [email protected] Send anywhere from 1 to 10 pages per mailing by email (Word docs) please!

Category Archives: Radio Memories

Video: Building Bethany – VOA’s First High-Power International Broadcast Station

Many thanks to the National VOA Museum of Broadcasting for posting the following video on their YouTube channel:

Guest Post: Pre-Internet Sources of Shortwave Information

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Dan Greenall, who shares the following guest post:

Sources of SWL Information “Pre-Internet”

by Dan Greenall

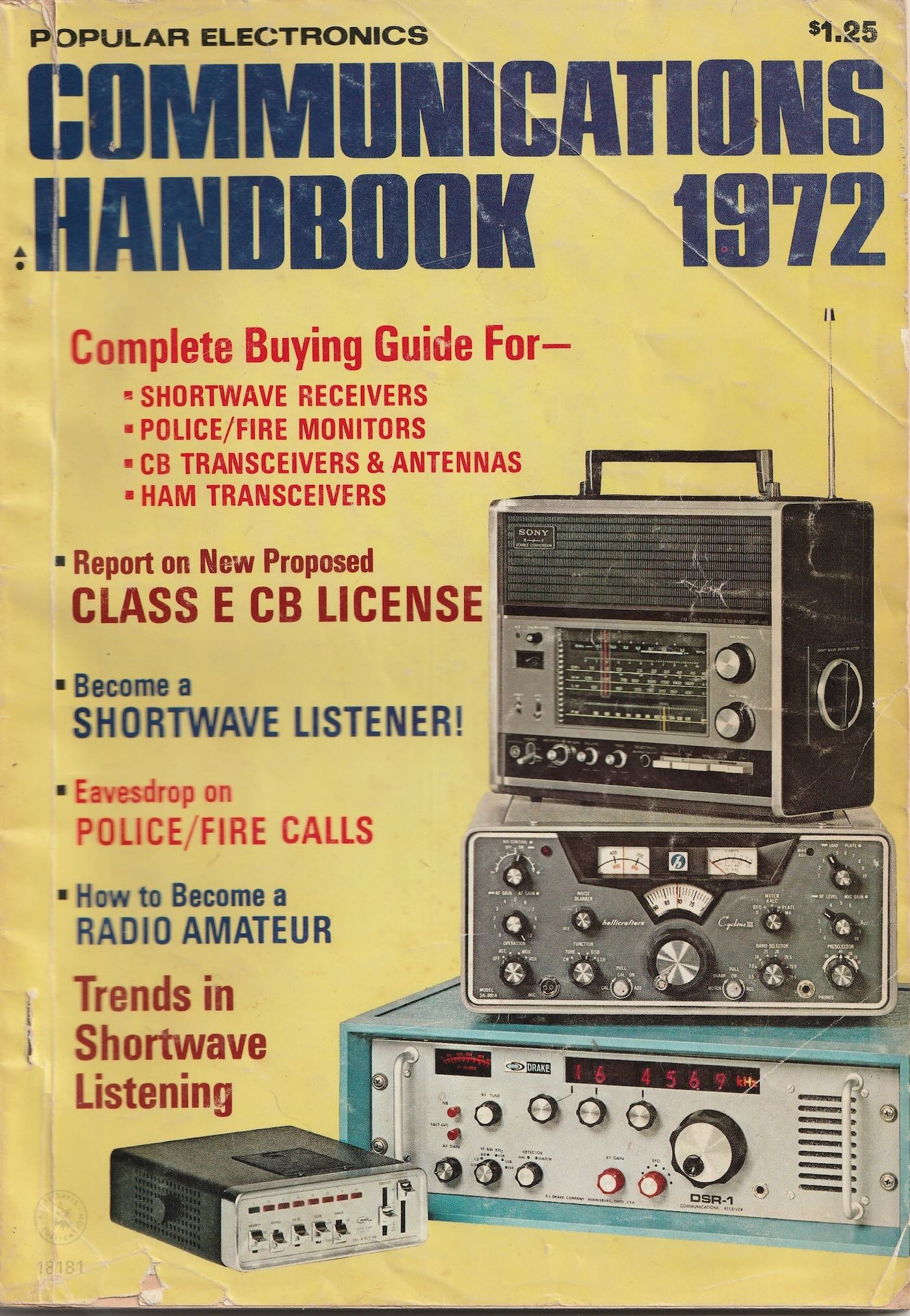

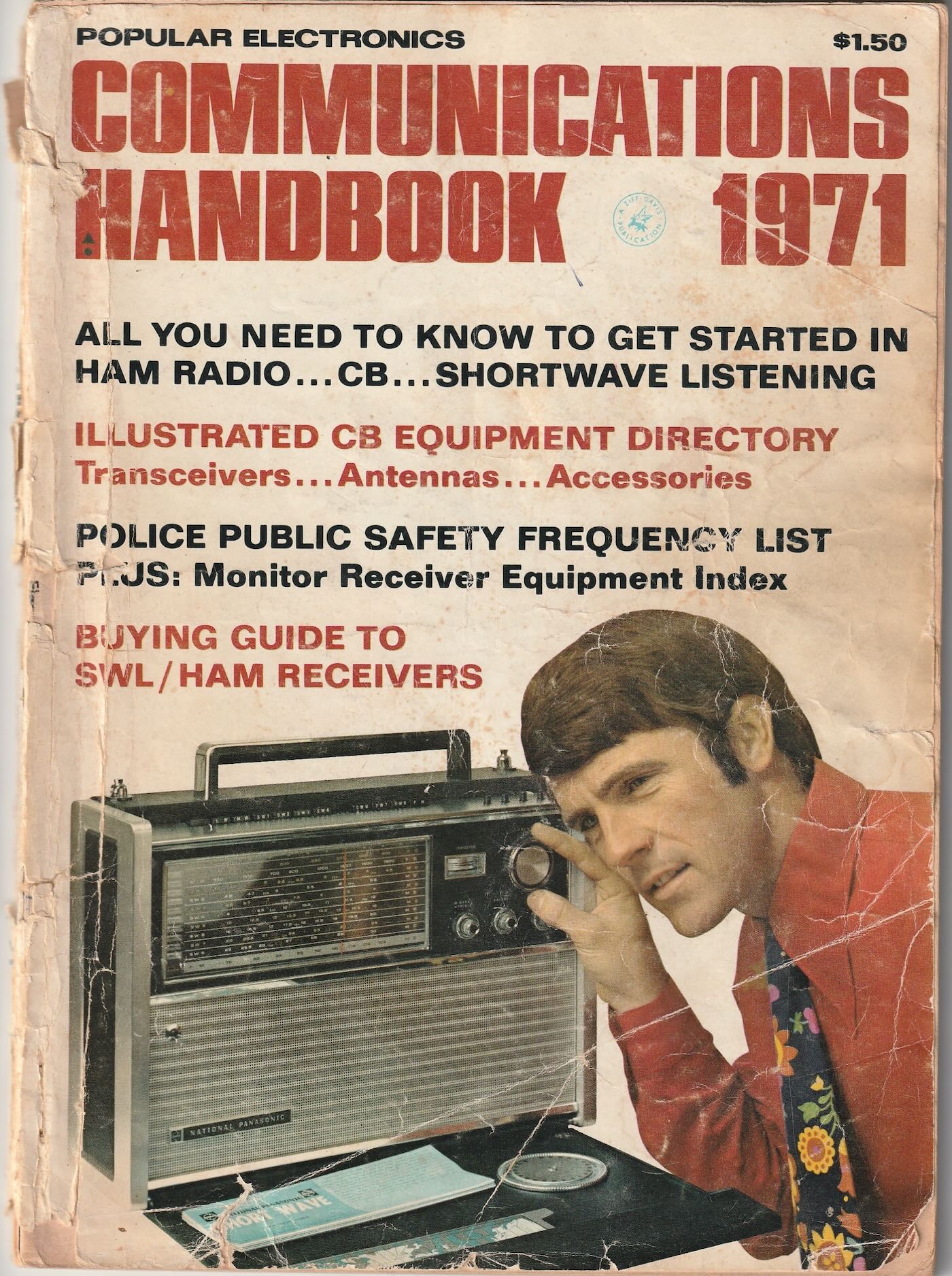

When I first discovered the world of shortwave listening, many years before the internet, access to hobby related information was mostly available through over-the-air DX programs, monthly DX club bulletins, as well as a number of books and electronics magazines. I joined a few clubs including the Midwest DX Club, SPEEDX, and the Ontario DX Association, and eagerly awaited each issue of Electronics Illustrated and Popular Electronics (early 1970’s) on the news stand. Later, in the 1980’s, Popular Communications and Monitoring Times came along, though these were not always easy to find here in Canada.

Ironically, nearly all issues of these magazines can be read today, over 30, 40 and even 50 years later, thanks to David Gleason’s not-for-profit, free online library

https://www.worldradiohistory.com/index.htm

You can also find the semi-annual (and eventually annual) Communications World (1971-81) which contained the popular White’s Radio Log.

As well, five issues of the Communications Handbook can be found; 1963, 1966, 1967, 1974 and 1977. It only came out once a year but was still a favourite of mine, so much so, that I still have my copies from 1971 and 1972.

I have scanned parts of these and put them on the Internet Archive. You can find them here:

I have scanned parts of these and put them on the Internet Archive. You can find them here:

Communications Handbook 1971: https://archive.org/details/page-09

Communications Handbook 1972: https://archive.org/details/page-20

Here are links that will lead to some of the other magazines:

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Popular_Communications.htm

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Monitoring-Times.htm

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Electronics%20_Illustrated_Master_Page.htm

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Popular-Electronics-Guide.htm

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/Technology/Hobbyist-Specials/Communications-Handbook-1974.pdf

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/Technology/Hobbyist-Specials/Popular-Electronics-Communications-Handbook-1977.pdf

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/Technology/Hobbyist-Specials/Popular-Electronics-Communications-Handbook-1967.pdf

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/Technology/Hobbyist-Specials/Communications-Handbook-1966.pdf

- https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-Poptronics/60s/63/Pop-1963-Communications-Handbook.pdf

As a bonus, all of the issues of the monthly SPEEDX bulletin (1971-95) have been made available here

https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Speedx.htm

And finally, a good read is Shortwave Voices of the World by the late Dr. Richard E. Wood written in 1969. I still have my copy of it, but you can find it online here

https://archive.org/details/shortwave-voices-of-the-world-richard-wood-ed-1-pr-1-1969

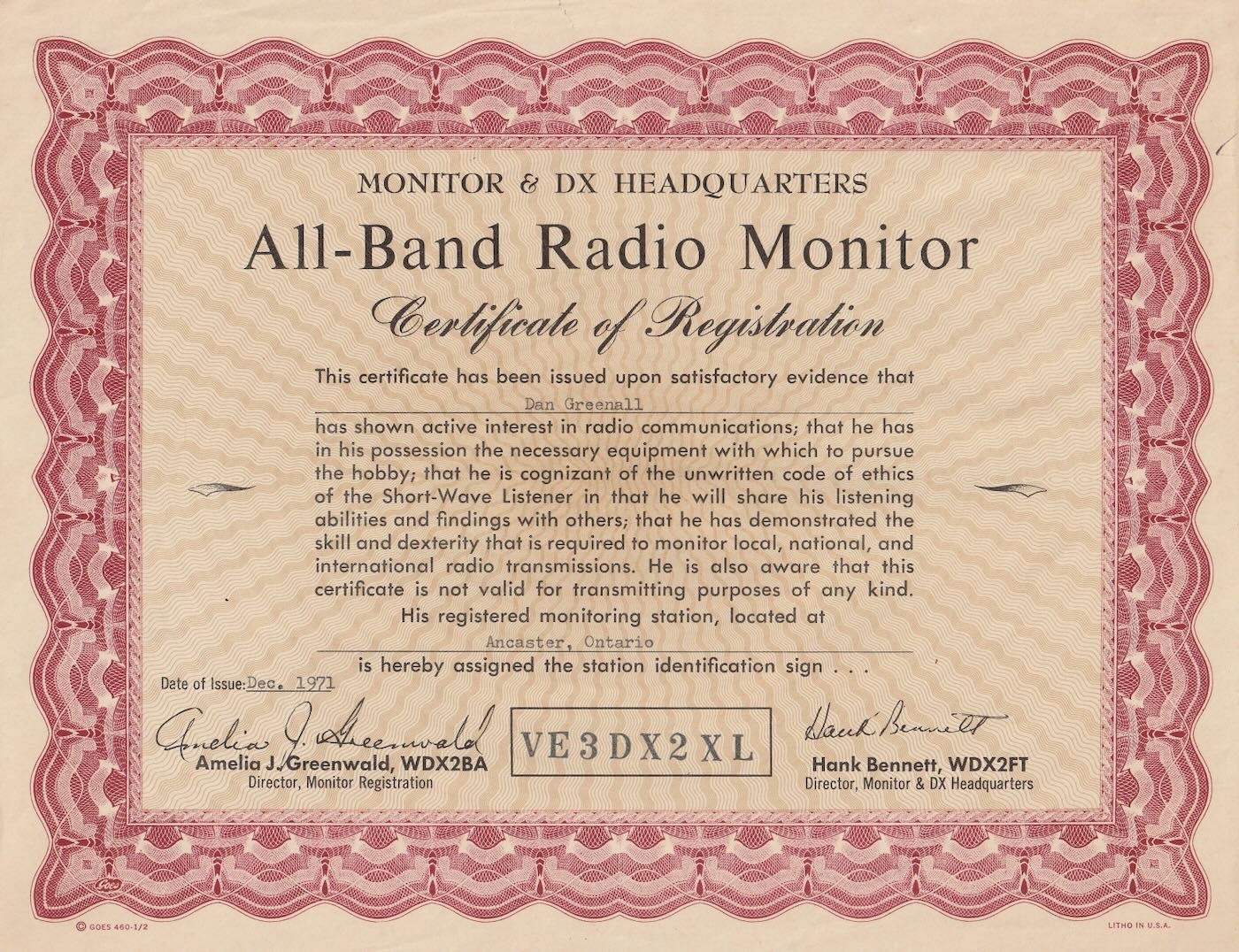

WDX SWL registration program

My link to the 1971 Communications Handbook contains pages regarding the old WDX SWL registration program. I have found my old certificate from December 1971:

Wonder how many others still have theirs, or even the WPE ones from the 1960’s?

Carlos’ Experience and Motivation for Receiving Kydodo News via Radiofax

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, friend, and political cartoonist Carlos Latuff, who shares the following guest post:

My experiences receiving Kyodo News

by Carlos Latuff

Back in the 90s, I used the fax machine a lot, I even had one in my house, sending messages and cartoons to my clients and even to live TV shows (see the video example below). Lots of fun!

But for me, the fax only worked through the phone line.

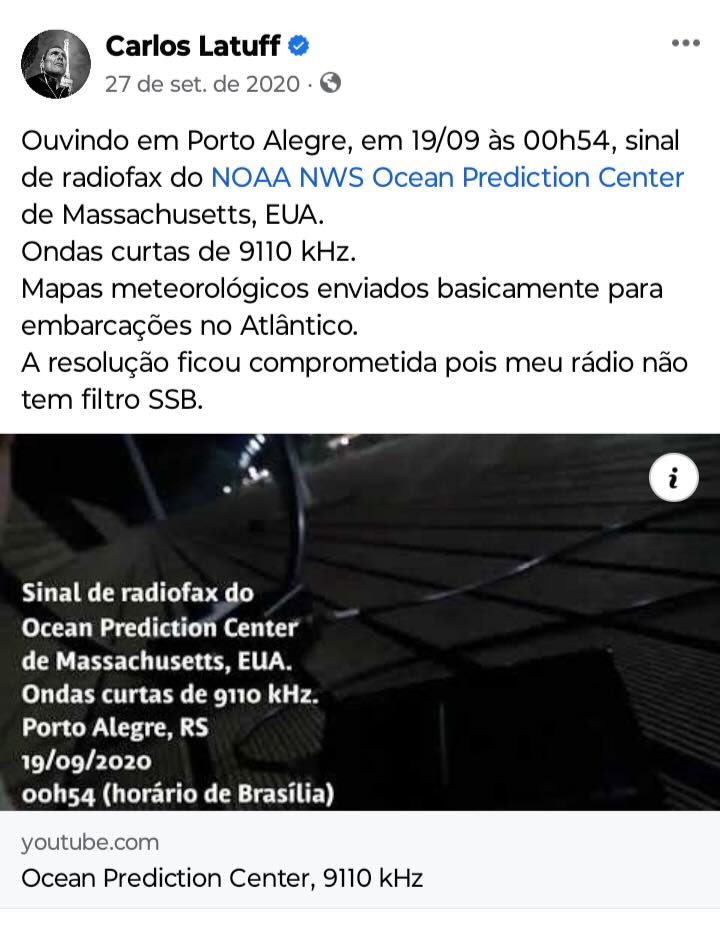

It was only in 2020, during the covid-19 pandemic, that I, by chance, during one of my radio listening sessions, came across a strange signal that I would only later discover was a radiofax.

It was then that I realized that several meteorological agencies around the world broadcast synoptic charts and satellite images to vessels on the seas by radiofax, and that there was a Japanese news agency (the only one left in the world) that broadcast daily news to fishing boats and cargo ships: Kyodo News.

I was fascinated by that!

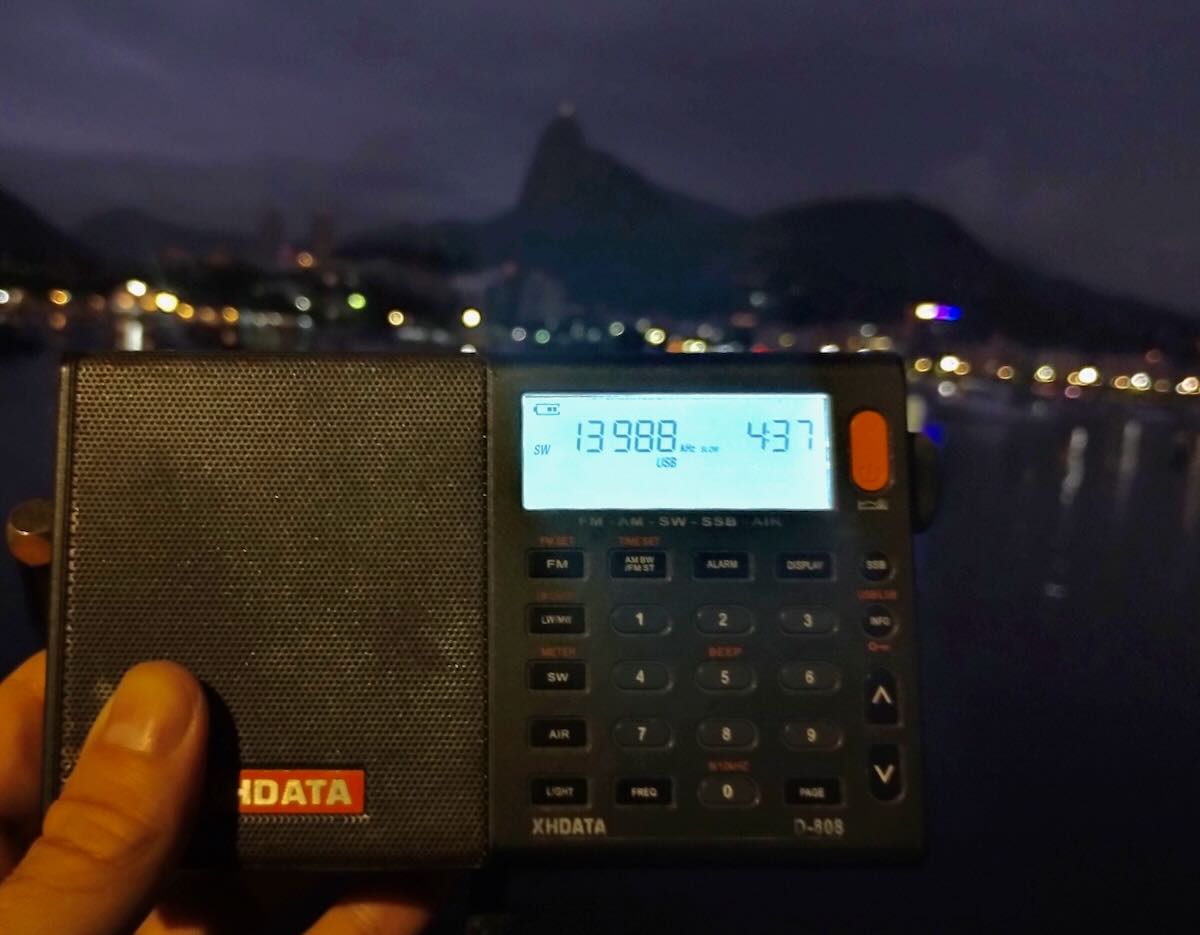

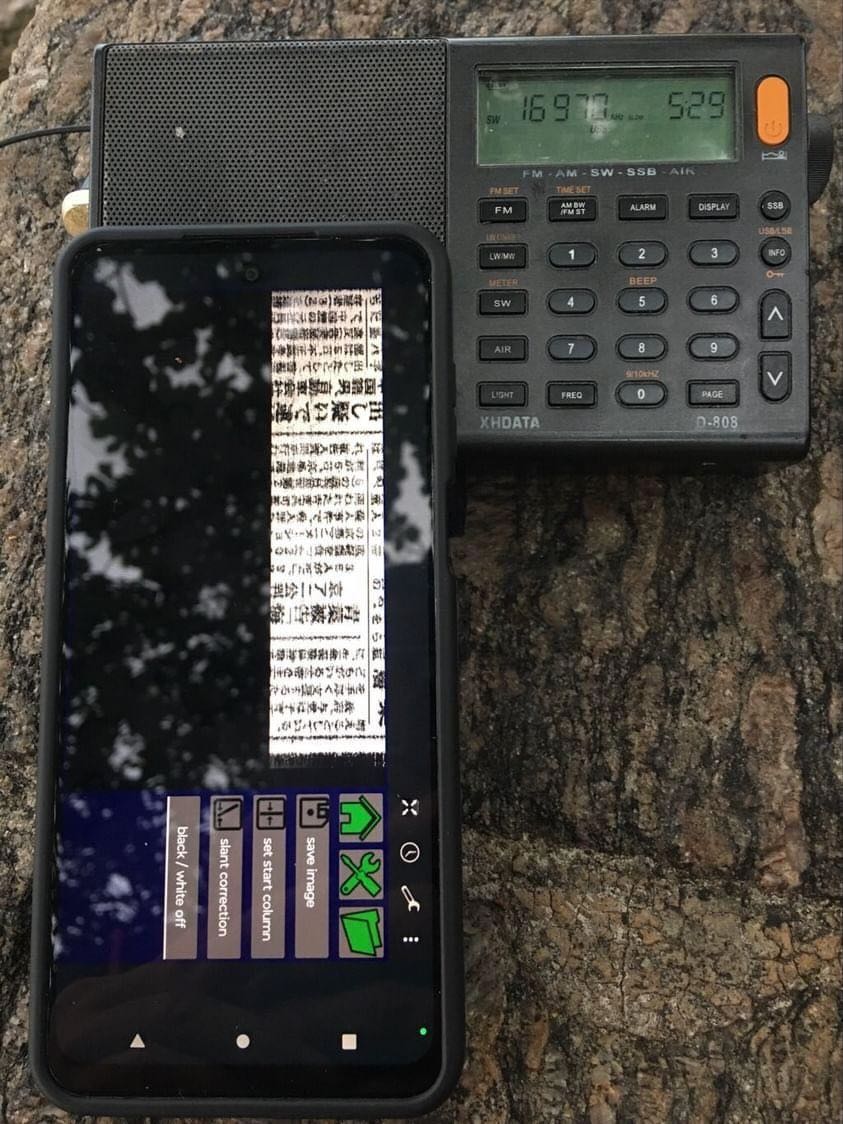

And I started tuning to the frequency of 16971 kHz USB (16970 in fact, to properly receive images) using basically my Xhdata D-808 and its telescopic antenna (now I use a 3-meter long wire antenna).

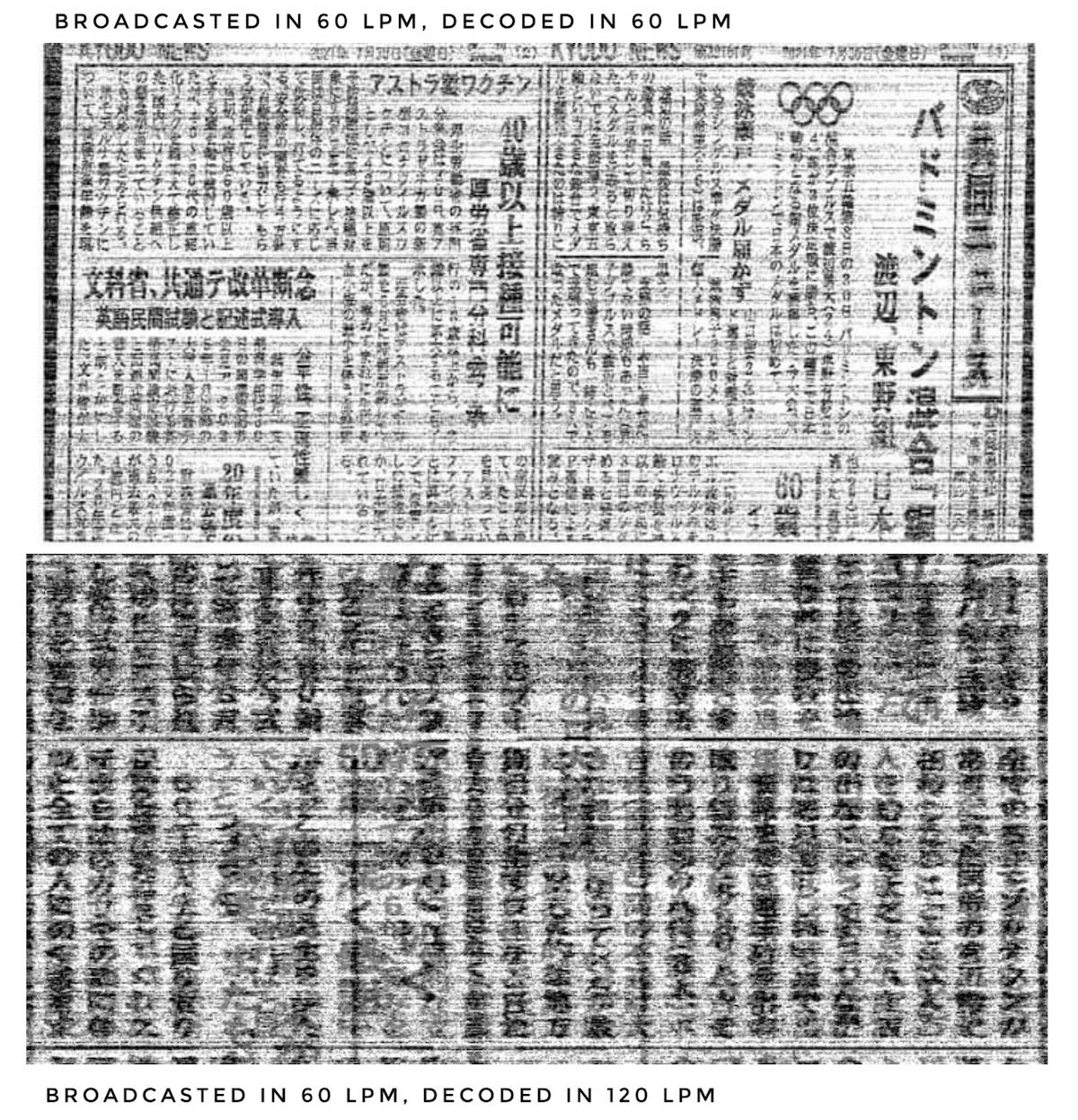

All the weather agencies I know broadcast at 120 lines per minute, while Kyodo News broadcasts at 60 lines. When I used to have a laptop, I had programs installed where I could adjust this cadence, like MixW, however, using an Android cell phone, the only application that works for radiofax is HF Weather Fax, which only decodes at 120 lines per minute (I had some problems with the app, which, being old, sometimes generated conflicts with Android and crash suddenly or even didn’t even open. Another bug is that after around 40 minutes of continuous decoding, the app stops). When you receive a radiofax at a rate of 60 lpm and decode it at 120 lpm, it’s as if you cut the image in half, vertically, and joined the two parts into one, mixing the letters.

I noticed that, when enlarging the image with my fingertips on the surface of the cell phone, while receiving the radiofax, I was able to see the right and left side of the image at a time, in an effect known in graphic arts as “moiré pattern”.

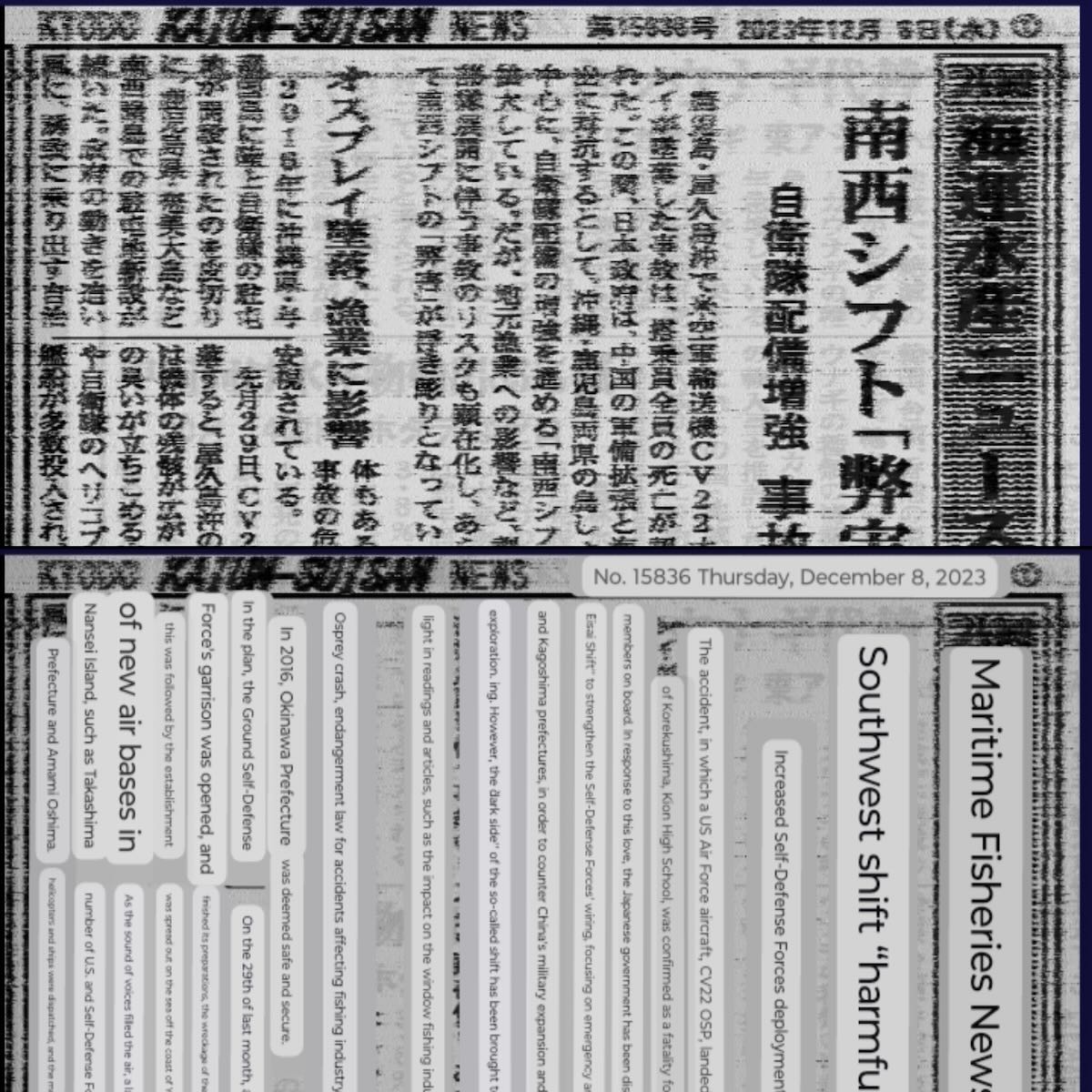

So, using HF Weather Fax I cannot download a Kyodo News radiofax in full (except when I receive the bulletin in English, the only time Kyodo News broadcasts in 120 lpm), but I can view parts of it and make print screens. And with these prints, I open them on Google translator app translating from Japanese to English. If image is in good quality, the translation is perfect.

Results I got were obtained from radio listening in Porto Alegre, Tramandaí beach in Rio Grande do Sul, and Urca beach in Rio de Janeiro, all located in Brazil. The best time has been late in the morning/early in the morning.

I’ve already obtained digital QSL cards from some meteorological agencies, such as those in Germany, Australia and Kagoshima in Japan, but Kyodo News doesn’t even respond to my emails.

But the main question is: why go to so much work to receive news via radiofax when you can easily receive it on the Internet through the Kyodo News website–?

Firstly, I’m nostalgic, receiving these radiofax has a touch of the past that I like to remember. And second, I believe that with the advancement of new satellite data transmission technologies, it’s only a matter of time before radiofax disappears as means of communication for vessels on the high seas. This is already happening!

Remember the end of radiofax transmissions from the New Zealand meteorological agency MetService this year?

So I’m enjoying the radiofax, before it ends!

The following are reports from some of my listening/decoding sessions: Continue reading

Radio Waves: WWFD All Digital, End of CBC Long Dash, HD Aviation Interference, NC Broadcast History Museum Plans, and Ukrainian Radio Resistant to Jamming

Radio Waves: Stories Making Waves in the World of Radio

Welcome to the SWLing Post’s Radio Waves, a collection of links to interesting stories making waves in the world of radio. Enjoy!

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributors Dennis Dura, Mark Koskinen, Stuart Smolkin, and Ron Chester for the following tips:

AM Digital WWFD Concludes Its Test Phase (Radio World)

The Hubbard station now is a full-time, all-digital operation

WWFD in Frederick, Md., has concluded the experimental phase of its MA3 HD Radio operation. It has notified the FCC that after five years, it will now continue to operate as a full-time all-digital AM station as is allowed under commission rules.

Dave Kolesar at a meeting of SBE Chapter 37 in Wheaton, Md.

The Hubbard-owned facility was the first AM station in the United States to convert to the MA3 mode, doing so under experimental authority in 2018.

Dave Kolesar, the engineer and program director who spearheaded the initiative and has given numerous presentations at engineering conferences about it, tells me that Hubbard recently asked the FCC to conclude the special temporary authority. [Continue reading…]

The end of the long dash: CBC stops broadcasting official time signal (CBC)

Segment connected Canadians, kept the country on time for over 80 years

The beginning of the long dash indicates exactly 1 o’clock eastern standard time.

For more than 80 years the beeps and tones of the National Research Council (NRC) time signal have connected Canadians at exactly 1 p.m. ET.

But as of Monday, CBC Radio One audiences won’t be listening for the beginning of the long dash — they’ll have listened to the end of it.

Variations of the daily message and the “pips” that sound along with it have played over CBC’s airwaves since Nov. 5, 1939 — forming a link that connects Canadians from coast to coast to coast.

CBC and Radio-Canada have announced they’ll no longer carry the National Research Council (NRC) time signal.

Monday marked the last time it was broadcast, ending the longest running segment on CBC Radio. [Continue reading and listen to the report on the CBC...]

Xperi Discussing HD Radio Power Boost Proposal With Aviation Groups (Radio World)

The Aerospace Industry Association and the Air Line Pilots Association International have voiced interference concerns

Several aviation groups have recently expressed concern about the potential for interference on navigation systems if a proposal to increase power for digital FM stations in the United States is adopted. Now, HD Radio developer Xperi said it is working to address those concerns.

In comments filed with the FCC (MB Docket 22-405), the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA) and the Air Line Pilots Association International (ALPA) raised the possibility of interference between HD Radio stations at 107.9 MHz and the adjacent Aeronautical Radio Navigation Service (ARNS) band operating from 108.0 – 117.975 MHz.

The ARNS band is occupied by safety critical navigation and landing systems essential for safety of flight, according to the groups. They include Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) needed for landing during low visibility conditions at night and during inclement weather. [Continue reading…]

State Broadcast Leaders Announce Plans for Broadcast History Museum in North Carolina (Beasley Media)

State broadcast leaders have unveiled details of a North Carolina Broadcast History Museum. Details were announced during a press conference that took place on Friday, October 13th at the Governor’s Mansion in Raleigh, NC.

The museum initiative is a 501(c) 3 non-profit corporation dedicated to preserving North Carolina’s broadcasting legacy.

North Carolina has a rich broadcast history, dating back to March 1902, when radio pioneer Reginald Fessenden transmitted a 127-word voice message from his Cape Hatteras transmitter tower to Roanoke Island. Then fast forward to July 23, 1996, when WRAL-TV became the first television station in the United States to broadcast a digital television signal. The state has been and continues to be a wealth of pioneers and innovators in industry.

North Carolina has been and continues to be a wealth of pioneers and innovators in industry. The State has numerous famous broadcast personalities, including Andy Griffith (born in Mount Airy), Charles Kuralt and David Brinkley (both from Wilmington), National Sportscaster Jim Nantz (from Charlotte), and National Public Radio Newscaster Carl Kasell (from Goldsboro).

The Museum is seeking assistance from the public and people who worked in broadcasting to collect artifacts, documents, photographs and recordings that chronicle the history of prominent radio and television stations, broadcasters, programs and events. Through exhibits and collections, the Museum seeks to highlight the contributions made by North Carolina Broadcasters in shaping the industry and the state’s culture landscape.

The Museum is guided by a distinguished group of broadcast professionals that include Caroline Beasley, CEO, Beasley Media Group; Don Curtis, CEO, Curtis Media Group; Jim Goodmon, CEO, Capitol Broadcasting Co.; Wade Hargrove, media lawyer; Harold Ballard, Broadcast Engineer; Carl Venters, Jr., Broadcast Executive; David Crabtree, CEO, North

Carolina Public Media, Dr James Carson, Broadcast Executive; Jim Babb, Broadcast Executive, Cullie Tarleton, Broadcast Executive, and former member of the NC House of Representatives; Dave Lingafelt, Broadcast Executive, Carl Davis, Jr., Broadcast Engineer, Jim Heavner,

Broadcast Executive, and Mike Weeks, Broadcast Executive.

The North Carolina Broadcast History Museum web site will serve as a digital repository accessible by the public that will grow in content and importance as items are gathered and

displayed. The museum web site is under construction and currently available online at www.NCBMuseum.com. Future plans include a brick-and-mortar facility for education, inspiration and enjoyment.

For more information, please contact Michael Weeks, North Carolina Broadcast History Museum Board Trustees Chairman, at [email protected] or call 252-721-0470.

Ukraine claims to have invented a new radio that’s immune to Russian jamming (Business Insider)

Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov announced on Tuesday the launch of radio technology that “cannot” be blocked by Russian jamming.

Fedorov, who also serves as Ukraine’s Minister for Digital Transformation, wrote on Telegram that the Himera radio is “a unique technology that works despite enemy electronic warfare,” according to Ukrainska Pravda’s translation.

“The Russians cannot block the radio’s signals or decrypt it,” he said, adding: “The radio can also be integrated into a situational awareness system or used as a GPS tracker to search for and evacuate soldiers.”

Russia’s electronic warfare capabilities have long proved a thorn in Ukraine’s side, as Michael Peck previously reported for Insider.

Russia has managed to achieve “real time interception and decryption” of the Motorola walkie-talkie systems in widespread use by Ukraine, according to a May report by the Royal United Services Institute. [Continue reading…]

Do you enjoy the SWLing Post?

Please consider supporting us via Patreon or our Coffee Fund!

Your support makes articles like this one possible. Thank you!

Don Moore’s Photo Album: Loja, Ecuador

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Don Moore–noted author, traveler, and DXer–for the latest installment of his Photo Album guest post series:

Don Moore’s Photo Album: Loja, Ecuador

Don Moore’s Photo Album: Loja, Ecuador

by Don Moore

A few months ago I did a two-part feature on my favorite small Latin American city, Cuenca, Ecuador. This time let’s journey to a nearby smaller city that I don’t know very well but want to spend more time in.

Loja is about two hundred kilometers south of Cuenca on a paved highway that runs through a long valley before climbing into the mountains to twist and turn the rest of the way. Look at the route on Google Maps and you’ll see what I mean. Today it’s a picturesque four-hour bus ride but when I made the trip the first time in 1985 it was a tortuous twelve-hour journey on rough dirt roads.

The roads today may be smooth and paved but Loja is still the most isolated major town in Ecuador. The city is so far south that it is closer to the Peruvian border than it is to any other town of size in Ecuador. This isolation has both forced the region to be self-reliant and cushioned it from problems in the rest of the country. For three years in the mid-1800s the province of Loja even governed itself as a peaceful independent country while the rest of Ecuador was mired in a bloody civil war.

Loja’s population of around 200,000 (a third the size of Cuenca) makes it the twelfth largest city in Ecuador. But Loja is one of those places that has always punched above its weight. The economy is strong as it’s the center of one of the best coffee growing areas in South America and the city is the main transit point for the gold fields to the east in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Loja is widely thought of as the most cultured and educated city in the country. Two of its universities rank in the country’s top ten. And everyone agrees that Loja is the center of Ecuadorian music. One of the city’s several museums has room after room filled with displays about the many famous musicians that have come from (and continue to come from) Loja. Free concerts are held in the city’s plazas at least once a week.

Loja has always been forward-looking. In 1890 the city installed one of the first hydroelectric generators in all of South America. That was just eight years after the first plant was installed in the United States. A little over a century later, in 2013, the first windfarm in continental Ecuador was constructed on a ridge above the city. The eleven windmills produce sixteen megawatts and phase two of the project, which is now under construction, will add another forty-six megawatts. A recently approved third phase will add another 110 megawatts.

The First Visit

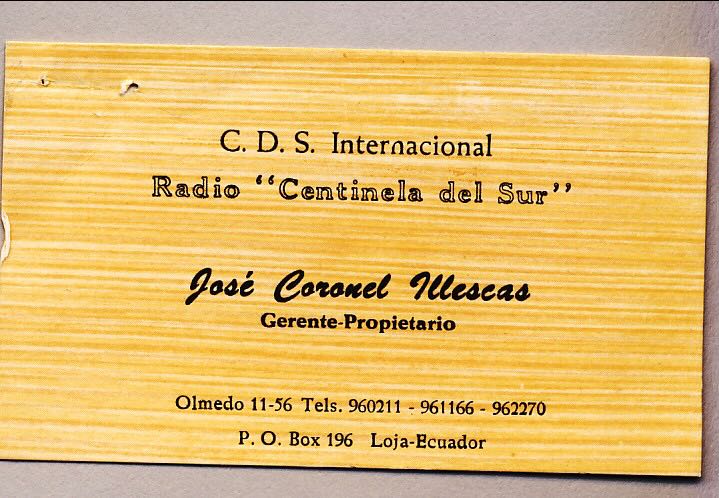

My first visit to Loja was in March 1985 after that long twelve-hour bus ride from Cuenca. I remember Loja as being a pretty but sleepy small city. We only stayed two nights and one day. My primary goal was to visit Radio Centinela del Sur and get a QSL for myself and several friends. I don’t recall anything from that long ago visit but I did get the QSLs. Radio Centinela was founded in 1956 so it wasn’t the first radio station in Loja. But it was the first one to last for more than a few years. On shortwave Radio Centinela del Sur was a station that changed frequency a lot. I first heard it in 1974 on 5020 kHz but most of my logs were made in the early and mid-1980s when 4890 kHz was in use. In the 1990s Radio Centinela del Sur used 4771 and 4899 kHz at various times. The station left shortwave for good by the late 1990s.

The second oldest station in Loja was Radio Nacional Progreso, founded in 1958. I have many logs of the station on its 5060 kHz (variable) frequency from the 1970s through the 1990s. I don’t remember why I didn’t visit them in 1985. Maybe the office was outside of town and difficult to get to. Loja’s other shortwave station was the Catholic broadcaster Radio Luz y Vida, founded in 1967. In the early 1970s the station used 4825 kHz on shortwave but around 1978 they switched to 4850 kHz. I last logged them there in 1997. Radio Luz y Vida was only a few blocks from our hotel and I stopped by several times but the inner door was always locked and I never got to see more than the entrance way. Continue reading

Radio Waves: FCC Issues FM Pirate Warnings, Shortwave Modernization Petition Comments, Morse Code Love, and The Art of Listening with BBC Monitoring

Radio Waves: Stories Making Waves in the World of Radio

Welcome to the SWLing Post’s Radio Waves, a collection of links to interesting stories making waves in the world of radio. Enjoy!

Many thanks to John Smith and Chris Greenway for the following tips.

FCC Issues Nine Warnings To Miami Area Landowners And Property Managers For Illegal Radio Broadcasts (FCC Press Release)

The PIRATE Act Prohibits Landowners and Property Managers from Aiding Pirate

Radio Operations

—

WASHINGTON, July 21, 2023—The FCC’s Enforcement Bureau today issued nine warnings to landowners and property managers in the Miami area for apparently allowing illegal broadcasting from their properties. The FCC may issue a fine exceeding $2 million if it determines that a party continues to permit any individual or entity to engage in pirate radio broadcasting from any property that they own or manage.

“Providing a safe haven for pirate radio operations that can interfere with licensed broadcast signals and fail to provide emergency alert system notifications can have serious consequences for landowners and property managers that allow this conduct to occur on their properties,” said Loyaan A. Egal, Chief of the Enforcement Bureau. “I want to thank our field agents for their continued efforts to ensure compliance with federal law in this area.”

The Notices of Illegal Pirate Radio Broadcasting sent today target properties identified by

Enforcement Bureau field agents as sources of pirate radio transmissions. These notices formally notify landowners and property managers of the illegal broadcasting activity occurring on their property; inform landowners and property managers of their potential liability for permitting such activity to occur on their property; demand proof that the illegal broadcasting has ceased on the property; and request identification of the individual(s) engaged in the illegal broadcasting.

The PIRATE Act provides the FCC with additional enforcement authority, including higher

penalties against pirate radio broadcasters of up to inflation-adjusted amounts of $115,802 per day with a maximum of $2,316,034. In addition to tougher fines on violators, the law requires the FCC to conduct periodic enforcement sweeps and grants the Commission authority to take enforcement action against landlords and property owners that willfully and knowingly permit pirate radio broadcasting on their properties.

The Notices of Illegal Pirate Radio Broadcasting are available at:

https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-issues-warnings-allowing-illegal-radio-broadcasts.

Shortwave Modernization Petition Comments (FCC)

Readers note that the number of comments on the Shortwave Modernization Petition have surpassed well over 600 at time of posting. No doubt, this particular petition is getting more visibility and notice than expected.

Falling in love by morse code (ABC Radio)

You may know someone who met the love of their life through writing letters, and these days you’d be hard pressed to NOT know people who’ve met online… but have you ever come across someone who’s met her husband in Morse code?

Ulla Knox-Little knew that getting to do an expedition to Antarctica as the radio room operator would be a life-changing experience, but she never expected it to lead to her meeting the love of her life.

Hosted and produced by Helen Shield.

Click here to listen to this short radio piece.

The Art of Listening: BBC Monitoring and the Historical Significance of the Transatlantic Open Source Intelligence Relationship [VIDEO] (Readex)

Last month, Readex welcomed librarians to a special breakfast presentation at this year’s ALA Annual Conference in Chicago, IL. Dr. Alban Webb, lecturer of Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex, captivated the audience in attendance with his talk on “The Art of Listening: BBC Monitoring and the Historical Significance of the Transatlantic Open Source Intelligence Relationship”

Dr. Webb—a noted historian of BBC World Service—gave a fascinating and informative overview of the history of open-source intelligence (OSINT) and the role of BBC Monitoring, highlighting perspectives these newly digitized archives represent for the study of the 20th century history. Click here to read the full article.

Do you enjoy the SWLing Post?

Please consider supporting us via Patreon or our Coffee Fund!

Your support makes articles like this one possible. Thank you!