The Edward R. Murrow Transmitting Station’s main building, located in the center of the 2800 acres campus. (Click to enlarge)

The following is an article I wrote for The Monitoring Times magazine in April of this year. It’s a virtual tour of the newly-dedicated VOA Edward R. Murrow Transmitting Station in Greenville, North Carolina.

The Monitoring Times reaches a large audience, and following this articles publication, readers came out of the woodwork in praise of it–not because of my authorship, but because of the truly fascinating subject. Most humbling have been the many messages I’ve received from within the family of broadcasters under the flag of the BBG (VOA, RFA, IBB, etc.). As I posted a few days ago, morale can get pretty low at this site, and the dedicated technicians are most deserving of recognition. Many at the VOA site told me that it was the first article praising their work at this transmitting site–the business end of broadcasting, one which often gets overlooked.

The Edward R. Murrow transmission site is nothing short of jaw-dropping. The people behind its operation are warm, genuine, and dedicated to the mission of information-sharing. Touring the site was a dream come true for this SWLer, and this holiday season, I’m happy to share it with my readers here on the SWLing Post.

Though there’s no obligation, if you enjoy the SWLing Post and are in the holiday spirit, feel free to send the SWLing Post a tip in any amount. It’ll help us keep the lights on, and bring you more articles like this one.

This is a very long post. Grab a cup of coffee or tea and enjoy:

A tour of the Edward R. Murrow Transmitting Station

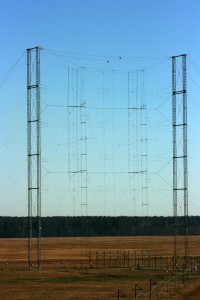

“The antennas are so incomprehensibly immense that even the photos we took fail to convey their enormity; there are no trees, no buildings, no vehicles–indeed, the only thing I could find for scale were deer, herds of them, running and leaping beneath.” (Click to enlarge)

During the final years of the Cold War, when I was a kid first tuning in to foreign broadcasters on my vintage Zenith Transoceanic, my imagination formed impressions of the voices I heard and the facilities required to send their messages. I saw Radio France International, for example, broadcasting from an Eiffel Tower-shaped structure just outside Paris, where glib, stylish reporters perched in front of their microphones. I envisioned Radio Moscow in black and white; likely because of what I’d only heard of life behind the Iron Curtain, my young mind defaulted to a nostalgic WWII like scene, with 1940s-era equipment, massive fields of antennas, desks heaped with papers awaiting translation, overly-full ash trays, and near-empty bottles of vodka. Voice of America, meanwhile, I imagined as a gleaming NASA-like facility with immaculate offices inhabited by reporters and engineers in horn-rimmed glasses, all engaged in a hum of activity at microphones and brightly-lit control panels. VOA, in my patriotic young mind, must be the most advanced facility of all: I could only imagine my own country’s contribution to the soup of international broadcasting as the best and freshest.

So some thirty years hence, presented with an opportunity to take a private tour of the VOA transmission site in Greenville, NC, with a few friends from the NCDXCC, my local ham radio club–Phil Florig (W9IXX), Dave Anderson (K4SV), and Phillip Jenkins (N4HF)–I naturally jumped at the opportunity.

As we drove out to the site, I could see why many of Greenville’s locals seem unaware of its existence, despite the facility’s vast size: it’s truly remote. On the mile-long driveway, we stopped the car, awed by the 2,715 acre expanse of open land, populated only by monolithic shortwave broadcast antennas. These structures are so incomprehensibly immense that even the photos we took fail to convey their enormity; there are no trees, no buildings, no vehicles–indeed, the only thing I could find for scale were deer, herds of them, running and leaping beneath. Clearly, these massive antennas mean business, and the ham radio operator in each of us stood at attention, in silent admiration.

Finally resuming our drive, we arrived at the security gate, where I picked up a phone to request permission to enter. Placing the phone to my ear, I heard music–Radio Martí, nonetheless! I noted. However, as the front desk answered the call, I noticed that the music didn’t stop: not hold music at all, it was simply the telephone absorbing the extraordinary impact of 500KW IBB transmitters engaged in their usual business.

Finally resuming our drive, we arrived at the security gate, where I picked up a phone to request permission to enter. Placing the phone to my ear, I heard music–Radio Martí, nonetheless! I noted. However, as the front desk answered the call, I noticed that the music didn’t stop: not hold music at all, it was simply the telephone absorbing the extraordinary impact of 500KW IBB transmitters engaged in their usual business.

The photo of Edward R. Murrow is displayed prominently in the lobby of the transmitting station. (Click to enlarge)

As we entered the lobby of the gleaming 1960s-era government building with its prominent portrait of Edward R. Murrow, we were warmly greeted by Macon Dail, Chief Engineer; Rick Williford, Program Support Specialist; and Walt Patterson, Station Manager. Williford provided an overview of the site’s history: the Edward R. Murrow Transmitting Station, as it is known, has always been a transmission site, delivering broadcasts through the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the 9/11 terror attacks. Under threat of closure in 2010, it found last-minute political support which has kept it in service. This was particularly fortunate in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake, as it was this site that broadcast extra VOA Creole services to the stricken country, programming that proved vital to the survival of many.

In the front lobby–from L to R Walt Patterson (Station Manager), Rick Wilford (Program Support Specialist), Phil Florig (W9IXX), Dave Anderson (K4SV)

Indeed, that political support galvanized in December of 2011, when Victor Ashe, a member of the Broadcasting Board of Governors, issued a call to keep open this broadcasting facility, as it is the only one on U.S. territory capable of transmitting shortwave radio programs to China–or to any country we please, for that matter. He noted that other facilities under the Broadcasting Board of Governors throughout the world operate in cooperation with other governments, many of which can limit broadcast targets.

Thus, support for the facility’s continuation continues to grow.

Following this insightful introduction, Williford and Dail led us upstairs to a tower on top of their building which offers a bird’s-eye, 360-degree view of the vast campus, a prime vantage point, and the start of a fascinating tour.

First QSL

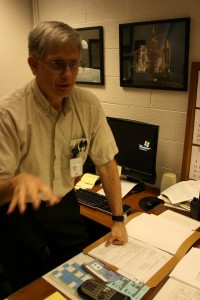

Macon Dail (WB4PMQ), we were soon to realize, is key to the lasting health of the Edward R. Murrow Transmitting Station. Dail has been working for VOA (or what is now the International Broadcasting Bureau) since 1984, and even looks the part, down to the collection of pens and tools in his shirt pocket. Dail led us to his office, where he proudly showed us one of the site’s first direct QSL reports, from a Japanese shortwave listener who had identified a Radio Martí transmission intended for Cuba. At the time, VOA had only begun the process of receiving QSLs directly, thus were encouraged by the prompt response, and from an area that was not technically within the footprint of their broadcast, a fact representative of the magic of shortwave radio (see QSL info at the end of the article).

Down the hallway from Dail’s office lies the heart of transmission site–the control room, where our tour officially began. The control room is exceptionally large, with two-story ceilings and a raised platform in the center. It’s from this raised platform that Dail showed us how content sources are controlled from the VOA headquarters in Washington, DC–content is sent to one of nine transmitters, and antennas selected based on the target footprint of the broadcast. The platform contains seating positions for several people; the mixture of 1960s technologies with current computer technology appears harmonious. On almost every control surface is taped a printed block chart transmission schedule for the broadcast season, with each space filled: obviously, knowing which program broadcasts, and when, is top priority here.

The control room contains the audio switching computer, remote antenna switching, and frequency synthesisers; it’s also where incoming and outgoing modulation levels are monitored. Moreover, this area is where off-air audio processing equipment is housed. An office for the shift supervisor is centered at the far end of the room.

The control room contains the audio switching computer, remote antenna switching, and frequency synthesisers; it’s also where incoming and outgoing modulation levels are monitored. Moreover, this area is where off-air audio processing equipment is housed. An office for the shift supervisor is centered at the far end of the room.

From almost every point within the control room, technicians can view a large digital clocks with UTC time synced to the atomic clock. Along the outer perimeter of the control room are the actual transmitters and their various controls, while a glass wall stands between the control room and each transmitter section.

Transmitters

Technician presetting the tuning controls of a GE 250 kW transmitter for the next operating frequency (Click to enlarge)

Dail then took us into the hallways on the perimeter of the control room where the transmitters are located. A quick walk through these halls, and one quickly recognizes that to work at this site you need to be familiar with the characteristics of transmitters from not just one or two manufacturers, but from at least four: Continental, GE, ABB, and Telefunken were all represented. Dail explained that this transmission site initially received equipment that had been intended for another facility that was later scrapped. And clearly, the VOA didn’t want to put all their eggs in one basket by relying on one type of transmitter only.

Dail then took us “behind the scenes” of a General Electric transmitter, quickly and expertly pulling panels off of protected portions of the mammoth transmitter, exposing a huge tuning coil, gears, and power regulation equipment. It became obvious that Dail knows this equipment as well as if it were in his home.

The site’s transmitters varied from the classic 1950s Continental to the ABB with fiber-optic controls, installed in the 1980s. The ABB transmitter, unlike the others at the site, is 100% solid state–no vacuum tubes–and by using a step modulator, broadcasts more efficiently than its predecessors.

Power supply

As the reader might imagine, it takes vast amounts of power to run transmitters emitting 500 kilowatts of electromagnetic radiation. Because of the extraordinary power consumption of the equipment, the VOA crew is ever-aware of their electronics engineering safety rules. Throughout the facility, one sees postings on the order of “Remember the Two Man Rule and use your ground sticks,” “Stay alive: use a ground stick,” and “Caution: 4160 Volts exposed through the top of this cubical — this transformer is live at all times.” Obviously, this was no playground, and we were careful walking amongst the humming transformers and high voltage equipment. But for the VOA techs, their safety routine is a familiar friend, as they grab ground sticks to insure no residual voltage is left in “powered-down” equipment, and take buddies along to double-check safety precautions when working in high-voltage areas.

Dail says that the facility’s power bills now run about $700,000 annually, and this is an improvement over the $2,000,000 spent previously. He then explained that he and his coworkers had “home-brewed” controller solutions that could better manage the distribution of power loads. By working with incremental power days, their massive on-site generator kicks in, parallel with the power company’s supply, to shift the heavy load when their overall grid demand is at its highest.

Indeed, creative adaptation is an oft-repeated refrain at the Murrow Transmission Station. Throughout the facility one notices ingenious solutions that help the facility’s crew manage an array of decades-old technologies in an efficient and current manner. Dail implemented most of these himself, and adds that this is his favorite part of the job. What, exactly, makes this work interesting? “Having to fix a problem, in a creative way, and in the process increasing overall efficiency,” Dail reveals. Much of his handiwork has been inspired by the ham radio world, as–first and foremost–Dail is a ham radio operator, and has been one since his teens.

Indeed, creative adaptation is an oft-repeated refrain at the Murrow Transmission Station. Throughout the facility one notices ingenious solutions that help the facility’s crew manage an array of decades-old technologies in an efficient and current manner. Dail implemented most of these himself, and adds that this is his favorite part of the job. What, exactly, makes this work interesting? “Having to fix a problem, in a creative way, and in the process increasing overall efficiency,” Dail reveals. Much of his handiwork has been inspired by the ham radio world, as–first and foremost–Dail is a ham radio operator, and has been one since his teens.

Spare Parts

On the way out of the building, Dail guided us through a testing area, where VOA technicians like Dail build, modify, and test various components. He also took us through their inventory warehouse. In this environ, where it’s necessary to actively operate equipment which may have originated from manufacturers many years out of business, an ample stock of replacement parts is an absolute must. Dail and his crew meticulously maintain and catalogue thousands upon thousands of spare parts, many of which may be the only ones left on this planet.

The array of tubes and valves alone is staggering. Many take shapes I had never seen before, and others are so large as to require a special portable crane to lift them. At the Edward R. Murrow Transmission Station, employees do not simply discard damaged parts; they try to repair or salvage them whenever possible.

The array of tubes and valves alone is staggering. Many take shapes I had never seen before, and others are so large as to require a special portable crane to lift them. At the Edward R. Murrow Transmission Station, employees do not simply discard damaged parts; they try to repair or salvage them whenever possible.

Antenna Switching

Perhaps the most surprising facility on the site is the “switch bay”–in essence, their antenna switch. While my antenna switch in my shack at home is the size of a thick paperback book, The Murrow Transmission Site’s antenna switch is a 75 x 150 foot building. It’s massive, and probably can be seen from space (Google Earth certainly gives you a good look at it). All of the transmission lines are overhead in this massive corrugated building with a dirt floor. Dail had one of the guys in the control room switch an antenna–the pneumatically-controlled system snapped into place, the sound suggesting steam train classic films, in which you can hear the points switching on the tracks.

On the exterior of the switching bay, parallel feed lines run in all directions to the VOA antenna farm. These lines are all exceptionally large versions of the ladder line many hams use in our shacks. Instead of 16 or 18AWG solid copper conductors, theirs are ?” outer diameter copper tubes–300 ohm line, made to withstand more than 500kW.

The enormity of the antenna farm is difficult to capture, even with a wide angle lens (Click to enlarge)

The Antenna Farm

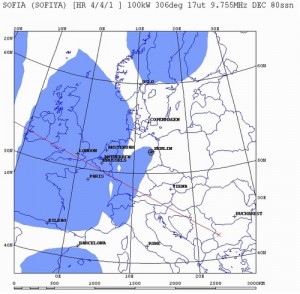

The VOA Greenville antenna farm consists of 20 rhombic, 19 curtain, 2 log periodics and 2 dipoles. Of the 43 original antennas, 50% are still in active use.

Dail drove us around the vast antenna farm, and we stopped to learn about each type of antenna. Of course, any time we alighted from the truck, we were looking at antennas that were inactive. When dealing with output levels as high as these, there would be serious dangers in walking around an active high-gain antenna; the numerous warning signs were a constant reminder of this sobering fact.

A view of the feed line manifold feeding the dipole elements of a curtain antenna (Click to enlarge)

Each of the antennas is a fascinating work of engineering, but the curtains are especially intricate. The sheer amount of stand-offs, insulators, and the parallel arrangement of elements were something to behold. The average curtain antenna is about 300 feet in height, 240 feet wide, with 20 DB of forward gain.

Perhaps the most fascinating antenna the site features, however, is near their campus entrance. It’s a 160 degree slewable curtain antenna that can literally adjust its angle to target any portion of Latin America. The slewable antenna has no moving parts other than the slew switches; rather, it uses phase-shifting to steer the beam.

I asked about lightening protection. Lightening? As far as Dail knows, the site has never experienced any damage due to lightening. Literally everything is grounded. While back home, I live in fear of lightening harming my shack, it occurred to me that here, perhaps the lightening is afraid of the antennas.

Wrapping up our tour

As we moved back into the main building, and our remarkable five-and-a-half hour tour drew to close, I still had not had enough time to take it all in. To add to my incredulity, Dail mentioned that, now decommissioned, VOA Site A is an identical twin of this site, once known as VOA Site B.

I thought he must be speaking figuratively. “Really?” I asked, ”It’s identical in size, in transmitter and antenna inventory? No way.”

These control room gauges monitor the many multi-lingual, simultaneous broadcasts coming from the transmitter site each and every day (Click to enlarge)

Dail calmly responded, “It’s identical, down to where the water fountains are placed in the main building.”

And as if that weren’t enough, there was a Site C, too–a receiver site only–at about the same distance, which was decommissioned in 1999 and sold to East Carolina University.

The Largest Thing

So, how does the reality of VOA Greenville compare with my childhood imaginings? While it’s not NASA, the Edward R. Murrow Transmission Station is much more…human. This, despite the fact that human becomes Lilliputian within the vast workings of the site. Touring this site was like touring the inside of a ham radio transceiver, one built on an absolutely astronomic scale.

Indeed, everything at VOA Greenville is overwhelmingly colossal–the transmitters, power supplies, the antennas. On our fantastic voyage among the gargantuan curtain and rhombic antennas surrounding the building, I could readily visualize the listeners’ side of the equation: remote corners of Africa and Latin America where it is a cinch to catch VOA’s broad signal with a simple, hand-held shortwave radio. I found myself suddenly reawakened to the brilliance of shortwave radio: unlike the internet, which requires infrastructure on each side, all the technology and brutal power of the shortwave radio medium is provided almost entirely by the broadcaster, thus listening requires very little. The messages conveyed by these powerful antennas travel every day, every hour, across closed borders with no regard for those in power, into remote areas with no power or basic services, inviting those with radios to simply listen. Radio, I reflected, is free speech in its most available, equitable form.

Macon Dail, Chief Engineer, and our tour guide in front of one of their Continental transmitters (Click to enlarge)

This is precisely the motivation behind the gentlemen of VOA’s Greenville site. Throughout the facility, I could see the handiwork and ingenuity of Dail and his co-workers; additions, modifications, notices, even wear on their oldest transmitters tell their ongoing story. The spirit of ingenuity and cause are in the hands and eyes of those we met that day; a sense of power and precision in the equipment. We left feeling that we had discovered Deus ex machina, and come face-to-face with Oz. Because, at the heart of it all, dedicated engineers are devoted to something largest of all: a humanitarian cause, which is to say, sending Voice of America and its award-winning news, documentaries, music, and Special English broadcasts to those with no more than a shortwave transistor radio, and the willingness to listen.

May it continue.

In this series of special holiday broadcasts, The Mighty KBC is targeting different regions of the world. See how many you can hear:

In this series of special holiday broadcasts, The Mighty KBC is targeting different regions of the world. See how many you can hear:

(Source:

(Source: