I love hearing stories about how shortwave radio listeners and ham radio operators got interested in the hobby. I’ll tell you about my experience, but I would enjoy hearing yours either in the comments section or by sending me an email. In the coming months, I will select stories to feature on The SWLing Post––especially if you have photos!

I love hearing stories about how shortwave radio listeners and ham radio operators got interested in the hobby. I’ll tell you about my experience, but I would enjoy hearing yours either in the comments section or by sending me an email. In the coming months, I will select stories to feature on The SWLing Post––especially if you have photos!

As I started to write a little of my personal history in radio, I felt a sense of déjà vu. That’s because in May 2011, Monitoring Times Magazine asked if I would write a piece describing how I became an SWLer and ham radio operator; of course this made for a nice segue into how I started the charity, Ears To Our World. After a little digging, I have discovered the unedited piece and added/updated where necessary.

So here’s my story–(now please share yours)!

[Update: Click here to read our growing collection.]

A Love of Listening: How I Relate to Radio

Growing up, listening…

I’ve never been a fan of television. Ironic, considering that I grew up in the seventies and eighties when most kids were glued to the tube, addicted to Nickelodeon. Perhaps one of the reasons why is that I find the visual often distracts from what I want to hear. Maybe it says something about my reluctance (or inability?) to multitask, but I’m much better at simply listening, rather than listening while also being asked to watch. I prefer to close my eyes, to just listen––and allow my mind to construct images from sound.

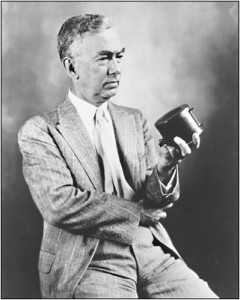

My father’s RCA 6K3 console radio.

When people ask how I became so interested in radio, the answer comes clear: I just love to listen. My father still has, in his living room, the vintage RCA 6K3 wooden console radio which emitted, like an aging, crackly-voiced Siren with her own kind of coarse charm, the various scintillating sounds that first caught my ear and captured my young imagination.

One of my earliest memories is of my father, tuning in WWV in Fort Collins, Colorado, on the RCA to set his watch to the atomic pulse coming through the aether, a practice he followed each Sunday morning. Sometimes he would allow me to tune around afterwards––on these occasions, I would catch broadcasts out of Europe, Australia, South America, as well as places I could not readily identify.

Not long after, my great aunt unearthed in her basement a classic Zenith Transoceanic, which she offered me; I took the dusty unit into my room and promptly set up a listening post. Little did I know at the time that I was joining a fraternity of radio listeners around the world who also logged and listened to stations, as I began to do, far into the night. I often fell fast asleep listening to my Zenith; no doubt, some of those mysterious DX stations I heard over shortwave and medium-wave infiltrated my dreams with languages and cultures altogether unlike my white-bread American one.

My trusty Zenith Trans Oceanic will always be a part of my radio collection (Click to enlarge)

Then when I was in my teens––again, in an ironic twist––a TV repair man who came to work on my parents’ set mentioned that he was a ham, and I was suddenly introduced to the intriguing world of ham radio. Though it took several years before I pursued my ticket, as I was busy with school, music, and other typical teen pursuits, my interest in the medium deepened.

While doing my undergraduate degree, I spent a year living and studying in France. At the time, the world wide web was still in its infancy, and my portable shortwave radio, which had helped teach me French back home, now became my English-speaking companion, bringing news from home courtesy of Voice of America. Unlike satellite television, cable TV, or an internet connection, radio was also inexpensive, vital for a poor student like me struggling to pay my own way in Europe. Through just listening, a virtual sonic flight home was free and nearly instant, arriving at the speed of light.

Mike Hansgen (K8RAT) teaching me the ropes at my first QRP Field Day in 1997. William McFadden was also there and was photographer for this photo. (Source: William McFadden WD8RIF)

After graduation, once more stateside, I encountered two hams who were to become lasting friends and elmers: Mike Hansgen (K8RAT) and Eric McFadden (WD8RIF). These two talented hams nourished my keen interest in the hobby, and in their company, I soon found myself in the field experiencing the scrappy fun of hands-on radio contests. I loved how my resourceful guides worked so many stations with the lowest-powered QRP equipment and only the simplest, cheapest wire antennas, and moreover, that they often derived their station power from the sun. I appreciated the remarkable skill with which they milked such modest equipment, initiating contacts all over the globe. With their steady encouragement, I finally got my ticket.

I’ve been a ham since 1997. Radio, no doubt, has influenced my decisions to travel, to live and work abroad, to pursue a graduate degree in Social Anthropology at the London School of Economics. Whatever I did, I did while listening to radio. I even changed my call not long ago to reflect my passion as a shortwave radio listener; my new handle is K4SWL.

Recently I found myself charmed and inspired by a BBC audio piece on Gerry Wells, the British radio repairman who in his eighties continues to do what he has always done, and is still sought for his skill. The story’s subject is truly enjoyable, if a bit of an anachronism: most remarkable is its relevance in the new millennium due to the simple fact that old mid-century (and earlier) radios continue to function today, and are still relied upon by listeners. As I listened to this report, I couldn’t help but wonder, as I have so often before: why does radio have such powerful nostalgic appeal? I reckon that, at least in part, it’s because radio has always been the voice of reassurance, of comfort, during darker times, reminding us that we are human, yet reminding us of our ability to survive. Radio is a friend––or, perhaps, a “great-uncle, in cords and a cardigan,” as Jeremy Paxman characterizes the BBC in his recent defense of this valuable institution in The Guardian––whose warm, familiar voice is there even when other media sources, or the internet, are down.

Shortwave, meanwhile, is much like the world’s pulse––we check in, we listen, and we confirm: all’s well, we’re still okay.

In this photo from Belize, I’m working with David (blue shirt), who is visually impaired–radio opens a world for him.

Listening as mission

One could say that listening to radio has shaped my life. I suppose that’s why radio has recently become a mission for me. Today, I’m the founder and director of Ears To Our World (ETOW), a charitable organization with a simple objective: distributing self-powered world band radios and other appropriate technologies to schools and communities in the developing world, so that kids like I once was, not to mention those who teach them, can learn about their world, too, through the simple act of listening. I want others––children and young people, especially––who lack reliable access to information, to have the world of radio within their reach.

Teacher in rural South Sudan with an ETOW radio. (Project Education Sudan Journey of Hope 2010)

Specifically, Ears to Our World works in rural, impoverished, and sometimes war-torn or disaster-ravaged parts of the world, places that lack reliable access to electricity (let alone the internet) and where radio is often the only link to the world outside. The heart of our mission is to allow radio to be used as a tool for education, so we give radios to teachers, who, in turn, use the radios in the classroom and at home to provide real-life, up-to-date feedback about the world around them.

Through the encouragement of our good friends at Universal Radio and the extraordinary magnanimity of Eton corporation, who donate our wind-up world band radios, in our first two years and on a budget of less than $3500, ETOW managed to distribute radios to schools and communities in nine countries on three continents––in Africa, Eastern Europe, Central and South America, and the Caribbean––as well as to both Haiti and Chile, where the dissemination of information through radio was life-saving when earthquakes struck.

Post-earthquake, ETOW radios continue to be a vital link for those in need in Haiti. Here, Erlande, who suffered a stroke in her early 30s and can barely walk, listens to one of our self-powered Etón radios, given to her by ETOW through their partner, the Haitian Health Foundation.

We’ve done all this through partnerships––with other reputable established non-profit agencies like us––that already help struggling schools throughout the world, and who believe, as we do, in freedom of and access to information. Creating these partnerships is an important move: due to the very nature of the remote regions we serve, extending our assistance demands persistence, financial resources, and logistical support, times ten. And often a great deal of patience. Just shipping radios to other countries usually involves detailed arrangements with national and regional governmental authorities (for example, to waive duties or taxes); once the radios arrive, safely distributing them to these remote areas can also be very costly and complex. We listen attentively to our existing partner organizations, who have often laid the groundwork in these regions, and have established reliable connections with communities in them. Their need is for resources—like radios.

By listening closely to and working cooperatively with other established organizations, we find we’re able to distribute radios much more cost-effectively, too. In other words, we can operate on a shoestring budget so that donations to ETOW are used wisely and to their fullest extent. For example, because of our strong partnerships, money otherwise spent on travel can be put into shipping costs instead, thus getting more radios to more of the world with less donated funds.

So far, our scope has been limited only by our financial resources. Meanwhile, we are looking to place radios in other countries farther off the beaten path; Mongolia recently received our radios. Yet we’re not simply focusing on expansion: ETOW is establishing strong, lasting bonds with our schools and teachers so as to better serve their needs long term. We endeavor to replace their equipment and batteries as needed. We would also like to develop on-air teacher training programs; a new partnership with Oklahoma State University seeks to develop and disseminate content on important subjects, among them literacy and health education, so there is new and valuable content to listen to.

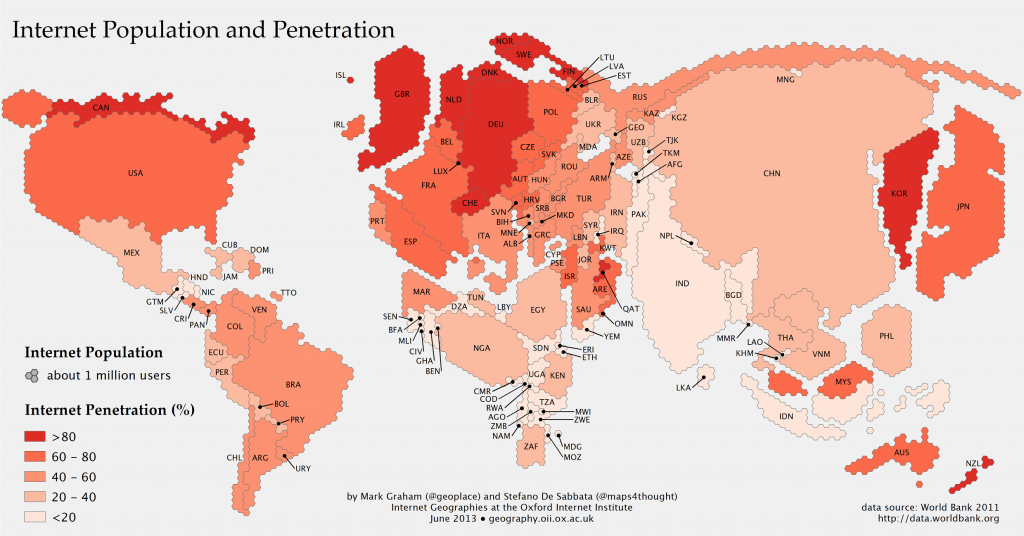

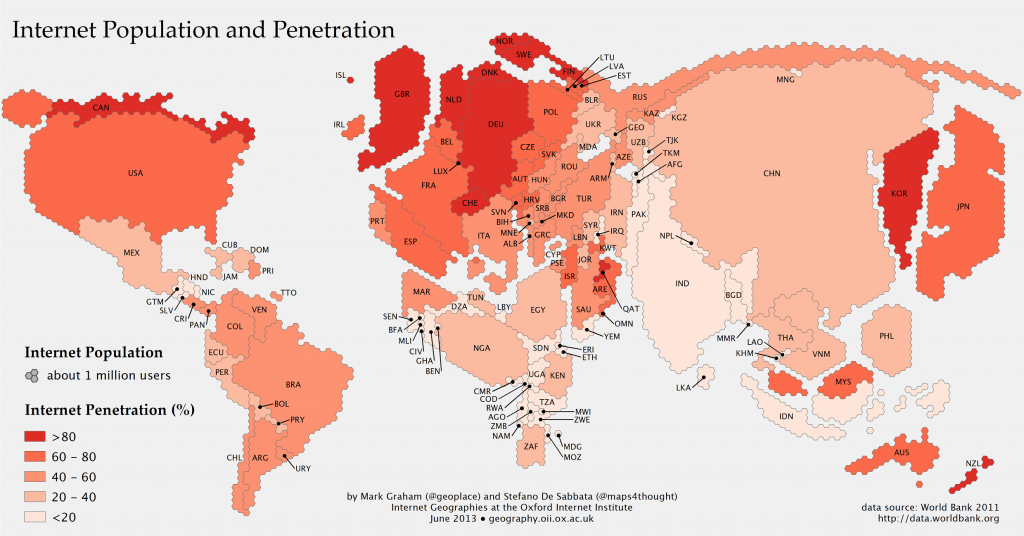

June 2013: This map shows the world adjusted for each country’s Internet population. Click to expand (Source: Information Geographies project at the Oxford Internet Institute)

MT readers [and especially SWLing Post readers] will have already guessed why we prefer radio to, say, computers, for information access. It is because much of the world does not have the communications infrastructure to support access to the world wide web and other dynamic media sources such as digital television, wireless networks or even electric power or phone. [Simply take a quick glance at the map above which shows the world adjusted for each country’s Internet population; notice how central Africa is all but missing?] Political instability, meanwhile, can undermine even the written word [for examples, check out our tag category: why shortwave radio?].

Radio, however, is simplicity itself: all one needs is a modest yet capable receiver, and one has instant––speed of light––access to local and world media. So far, every teacher we’ve worked with already knows something about radio; indeed, many of them have an intricate knowledge of broadcast schedules. But in these places it can take up to an entire week’s wages to pay for a set of batteries. Thus ETOW’s wind-up radios become vital–we effectively eliminate this cost, giving them steady access to information.

Radio, however, is simplicity itself: all one needs is a modest yet capable receiver, and one has instant––speed of light––access to local and world media. So far, every teacher we’ve worked with already knows something about radio; indeed, many of them have an intricate knowledge of broadcast schedules. But in these places it can take up to an entire week’s wages to pay for a set of batteries. Thus ETOW’s wind-up radios become vital–we effectively eliminate this cost, giving them steady access to information.

And the reports we’re hearing from the field have been overwhelmingly encouraging: Teachers in rural Mongolia, Tanzania, and Kenya are able to teach current events. Visually impaired children in rural Belize can listen to the outside world and hear music and languages they’ve never heard. Children in Haiti and families in Chile learned where to go to get food and medical care and information about loved ones affected by the quakes. A remote community in southern Sudan was able to listen to reports of their burgeoning country’s first democratic election. Being able to listen is making a difference.

Listening and learning work together

Radio captured my imagination as TV never could, it travelled with me and taught me early on that everyone has a story. Listening to radio taught me, too, that each voice is different in the consideration of what’s meaningful or newsworthy. I learned to understand––or at least appreciate––the diverse perspectives I heard in my vicarious radio journeys, and from these sprang my own opinions, hopes, beliefs. Radio became my teacher, one who gave me, in my formative years, a global perspective.

Students in South Sudan listen to their favorite shortwave radio program, VOA Special English.

Just as radio taught me, and opened my young mind, I’m convinced that it can teach and open the minds of others. In some parts of our world, futures are still written on the airwaves. But it’s never just a one-way street–willingness to listen to those with whom we work helps us better serve them, but also to make the leaps of mind required to cross cultures, to become aware of those outside our Western sphere, to understand and grow and learn, ourselves.

Listen and learn. That’s ETOW’s tag line, but to some young people––and to me––it still means the world.

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Want to help us give the gift of radio? Visit ETOW online at earstoourworld.org or write us at Ears To Our World, PO Box 2, Swannanoa, NC 28778, USA.

Your personal interest, or that of your local radio club or business, could put radios in a school or village in the most remote corner of the world.

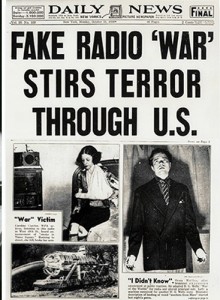

Without a doubt, one of the most famous broadcasts in radio history––indeed, in American history––was Orson Welles’ radio production of the H. G. Wells’ classic sci-fi novel, The War of the Worlds. A Halloween radio drama from the The Mercury Theatre on the Air series from the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), The War of the Worlds aired on October 30, 1938–exactly 75 years ago, today. And it’s still creating a stir…

Without a doubt, one of the most famous broadcasts in radio history––indeed, in American history––was Orson Welles’ radio production of the H. G. Wells’ classic sci-fi novel, The War of the Worlds. A Halloween radio drama from the The Mercury Theatre on the Air series from the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), The War of the Worlds aired on October 30, 1938–exactly 75 years ago, today. And it’s still creating a stir… Because many listeners tuned in the production without hearing the Welles’ introduction to the drama, they heard what sounded like a live news report of Martians attacking our planet. While it seems dubious today, what made Welles’ production so convincing was his innovative use of mock news breaks, and what listeners described as a “deafening” silence after a supposed “eyewitness report.” It sounded, in short, terribly authentic, and therefore convincing.

Because many listeners tuned in the production without hearing the Welles’ introduction to the drama, they heard what sounded like a live news report of Martians attacking our planet. While it seems dubious today, what made Welles’ production so convincing was his innovative use of mock news breaks, and what listeners described as a “deafening” silence after a supposed “eyewitness report.” It sounded, in short, terribly authentic, and therefore convincing. Then this morning, I read a rather provocative article by Jefferson Pooley and Michael Socolow in Slate; their mutinous view of the impact of Welles’ The War of the Worlds broadcast flies in the face of the American Experience and RadioLab documentaries and, indeed, every history textbook which devotes space to Welles. These authors claim:

Then this morning, I read a rather provocative article by Jefferson Pooley and Michael Socolow in Slate; their mutinous view of the impact of Welles’ The War of the Worlds broadcast flies in the face of the American Experience and RadioLab documentaries and, indeed, every history textbook which devotes space to Welles. These authors claim: I believe Welles’ controversial radio production did something for radio listeners regardless of the level of panic it may––or may not––have engendered. Welles’ Halloween production left them (and us) with a gift. How so?

I believe Welles’ controversial radio production did something for radio listeners regardless of the level of panic it may––or may not––have engendered. Welles’ Halloween production left them (and us) with a gift. How so? Regardless: whether Welles created widespread or merely local panic, or whether you even buy my theory that this production taught us to question what we hear, it’s difficult to deny that the Orson Welles’ production of The War of The Worlds was a brilliant, ground-breaking radio drama. And, I would add, great seasonal entertainment. Fortunately for us, almost 75 years later (nearly to the minute!), we can listen to archived recordings of the original CBS production.

Regardless: whether Welles created widespread or merely local panic, or whether you even buy my theory that this production taught us to question what we hear, it’s difficult to deny that the Orson Welles’ production of The War of The Worlds was a brilliant, ground-breaking radio drama. And, I would add, great seasonal entertainment. Fortunately for us, almost 75 years later (nearly to the minute!), we can listen to archived recordings of the original CBS production.