I had the pleasure of visiting the Champaign Aviation Museum recently and examining their under-restoration B-17G, “Champaign Lady”. Actually, the term “under-restoration” is incorrect. In actuality, the Champaign Aviation Museum is effectively building their B-17G nearly from scratch—quite an undertaking but one that the volunteers are performing skillfully and enthusiastically.

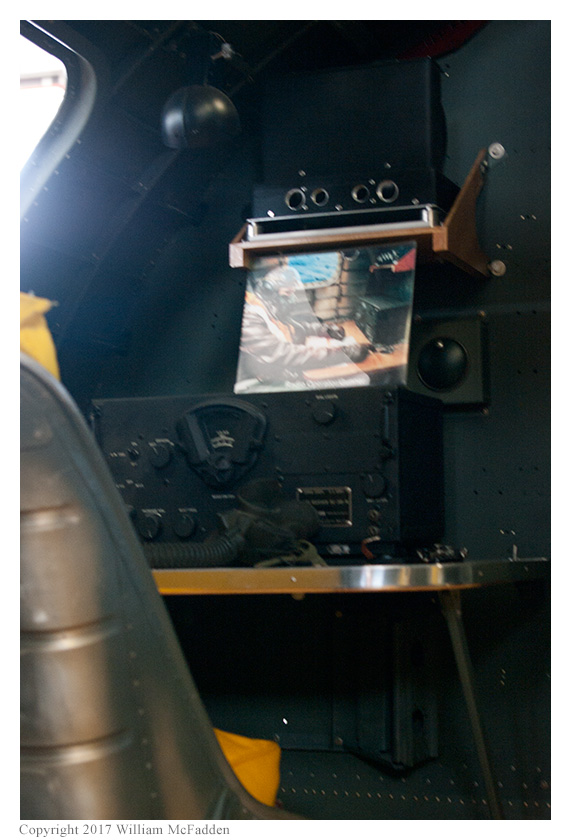

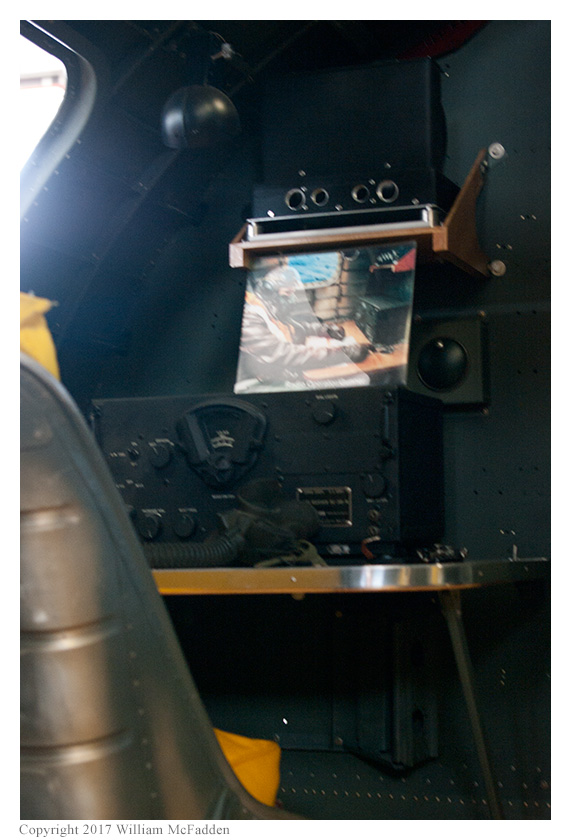

Being an amateur radio operator, shortwave listener, and would-be WWII-radio restorer, I was was pleased to see that Champaign Lady already has a nearly-complete radio-operator position installed, between the bomb-bay and the waist-gun section of the airplane. As a B-17G would have had during the war, Champaign Lady features a BC-348 liaison receiver and morse-code key mounted on a desk on the port (left) side of the bomber and a stack of AM/CW Command Set transmitters and receivers racked on the starboard (right) side of the bomber. In the photos, the top Command Set boxes are the transmitters and the bottom three Command Set boxes are the receivers. Of course, the BC-348 and the Command Set transmitters and receivers are fully tube-type, semiconductors having not yet been invented. During the war speedometer-type cables would connect the Command Set receivers to controls in the cockpit, allowing the pilot and co-pilot to control the Command Set receiver frequencies; electrical cables would have carried the receivers’ audio to the pilot and co-pilot and would have allowed them to change volume-level. The radio operator could transmit using the Command Set transmitters and could also switch the pilot or co-pilot intercom microphones to any of the Command Set transmitters to allow the pilot or co-pilot to broadcast to other bombers in the formation.

B-17G “Champaign Lady” radio operator position; BC-348 liaison receiver on the port (left) side and Command Set transmitters and receivers on the starboard (right) side.

B-17G “Champaign Lady” BC-348 liaison receiver and morse-code key.

B-17G “Champaign Lady” Command Set transmitters and receivers on the starboard side of the radio room

During the war, the B-17G radio operator was an enlisted man, typically a sergeant or higher in rank. If in an earlier version of the B-17G, the radio operator was also responsible for manning a .50 caliber machine gun located in his section of the airplane. In all versions of the B-17G, the radio operator assisted the navigator by providing position reports based on radio fixes of beacons or radio stations. Additional information about the role of the B-17G radio operator can be found on the B-17 Queen of the Sky website.

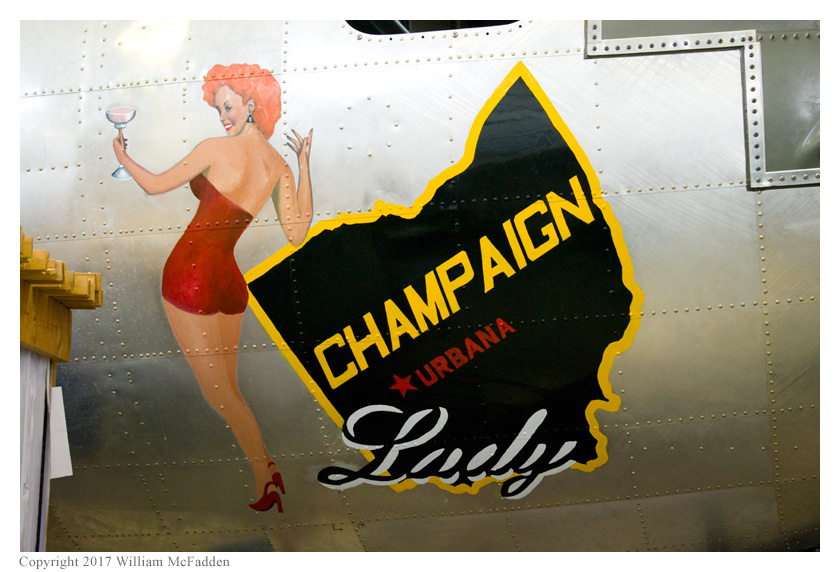

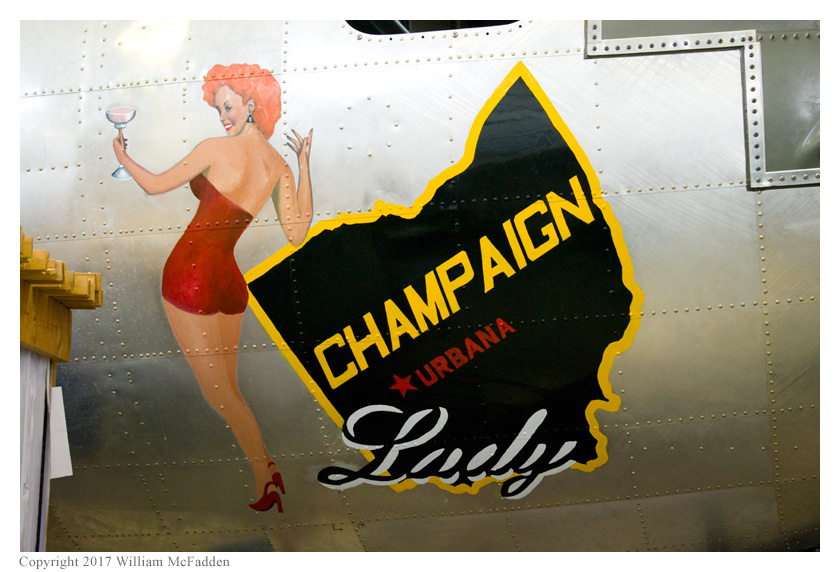

And, for those interested, here is what Champaign Lady’s nose-art looks like:

B-17G “Champaign Lady” nose-art, starboard side; the port side features a mirror-image version of the same design

The Champaign Aviation Museum has a beautifully restored B-25J, “Champaign Gal”, in flying condition. Unfortunately, I’ve not been able to see if Champaign Gal features a restored radio operator position.

I have a BC-224, which is the 12-volt version of the BC-348 liaison receiver to put back into service as well as a BC-696A Command Set transmitter that I hope to eventually put back onto the air in the 80-meter amateur band. It would be wonderful if I had a B-17G in which to install these items—or even just room to build a replica B-17G radio operator position!

73,

Eric McFadden, WD8RIF

http://wd8rif.com/radio.htm