Radio Waves: Stories Making Waves in the World of Radio

Radio Waves: Stories Making Waves in the World of Radio

Because I keep my ear to the waves, as well as receive many tips from others who do the same, I find myself privy to radio-related stories that might interest SWLing Post readers. To that end: Welcome to the SWLing Post’s Radio Waves, a collection of links to interesting stories making waves in the world of radio. Enjoy!

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributors Tony, Dan Robinson, Michael Bird for the following tips:

USAGM CEO Michael Pack thanks interim heads of agency’s five broadcasting networks (USAGM)

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Today, U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM) Chief Executive Officer Michael Pack thanked officials who will serve in an interim capacity as the heads of the agency’s two federal organizations and its three public service grantee broadcasting networks.

- Elez Biberaj, who has led Voice of America (VOA)’s Eurasia Division since 2006, will serve as VOA’s Acting Director.

- Jeffrey Scott Shapiro, previously Senior Advisor at Office of Cuba Broadcasting (OCB), will serve as OCB’s Acting Director and Principal Deputy Director.

- Parameswaran Ponnudurai, who has been Vice President of Programming at Radio Free Asia (RFA) since 2014, will serve as RFA’s Acting President.

- Kelley Sullivan, who has been a Vice President at Middle East Broadcasting Networks (MBN) since 2006, will serve as MBN’s Acting President.

- Daisy Sindelar, who has been with RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty (RFE/RL) for nearly two decades, will serve as RFE/RL’s Acting President.

CEO Pack sent, in part, the following message to staff:

“The experience of these talented men and women, their knowledge of the networks, and their commitment to the standards of journalism will allow us to launch into the next exciting chapter of our agency. Dr. Biberaj, Mr. Shapiro, Mr. Ponnudurai, Ms. Sullivan, and Ms. Sindelar will serve critical roles in allowing our networks to become higher performing and to more effectively serve our audiences. For their willingness to step up and help lead this effort, I am deeply appreciative. I am excited to serve alongside them as well as with all of you.”

Virginia Air & Space Center Ends Relationship with Ham Radio (ARRL News)

Virginia Air & Space Center (VASC) Executive Director and CEO Robert Griesmer has advised that the Center’s amateur radio station exhibit will be discontinued, effective July 1, when the Center, in Hampton, Virginia, reopens. VASC is the official visitor center for NASA’s Langley, Virginia, facility. The KE4ZXW display station was shut down on March 13. It was to be out of the VASC by June 30. A main feature of the exhibit was the ability to communicate with amateur radio satellites and with the International Space Station.

Randy Grigg, WB4KZI, of the VASC Amateur Radio Group said the station’s equipment would be relocated. “Thanks to all who have supported KE4ZXW during the last 25 years, especially the volunteer operators who manned the station during that time,” Grigg said. “To the many visitors we have met and school groups that have stopped by and talked with us about ham radio, communications, satellites, and STEM Program related subjects, thank you!”

On June 30, it was announced that the Virginia Tech Amateur Radio Association (K4KDJ) in Blacksburg will be the new host for the KE4ZXW Amateur Radio Demonstration. — Thanks to Randy Grigg, WB4KZI, and Ed Gibbs, KW4GF[…]

Why WWV and WWVH Still Matter (Radio World)

Last year was one of both celebration and uncertainty for WWV, the station adjacent to Fort Collins, Colo., that transmits automated time broadcasts on the shortwave bands.

On the plus side, it marked the 100th year of WWV’s call letters, making the site, operated by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, one of the world’s oldest continually operating radio stations.

On the negative side, WWV and its sister time station WWVH in Hawaii nearly missed this centennial. That’s because NIST’s original 2019 budget called for shutting down the pair, along with WWVB, the longwave code station co-located next to WWV, as a cost-saving move.

Fortunately, these cuts never happened, and WWV, WWVH and WWVB seem likely to keep broadcasting the most accurate time from NIST’s atomic clocks, at least for the immediate future. (No further cuts have been threatened.)[…]

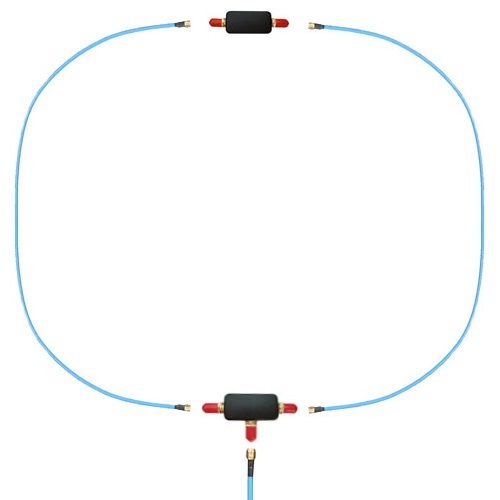

Another Shortwave WebSDR operational in Iceland (Southgate ARC)

On June 27, a new KiwiSDR web software defined radio became operational in Iceland

A translation of the IRA post reads:

The new receiver is located in Bláfjöll at an altitude of 690 meters. It has for the first time used, a horizontal dipole for 80 and 40 meters.

The KiwiSDR receiver operates from 10 kHz up to 30 MHz. You can listen to AM, FM, SSB and CW transmissions and select a bandwidth suitable for each formulation. Up to eight users can be logged into the recipient at the same time.

Ari Þórólfur Jóhannesson TF1A was responsible for the installation of the device today, which is owned by Georg Kulp, TF3GZ.

Bláfjöll: http://blafjoll.utvarp.com/The other two receivers that are active are located at Bjargtångar in Vesturbyggð, Iceland’s westernmost plains and the outermost point of Látrabjarg and at Raufarhöfn. Listen at:

Bjargtångar: http://bjarg.utvarp.com/

Raufarhöfn: http://raufarhofn.utvarp.com/The IRA Board thanks Ara and Georg for their valuable contributions. This is an important addition for radio amateurs who are experimenting in these frequency bands, as well as listeners and anyone interested in the spread of radio waves.

Source IRA https://tinyurl.com/IcelandIRA

KiwiSDR Network

http://kiwisdr.com/public/

Do you enjoy the SWLing Post?

Please consider supporting us via Patreon or our Coffee Fund!

Your support makes articles like this one possible. Thank you!