Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Mark Hirst, who shares the following guest post:

A Radio Postcard from Seoul

Hechi is a mascot for the Seoul Metropolitan Government

by Mark Hirst

I recently spent a very memorable week in Seoul, motivated to travel there by Hallyu or the Korean Wave, a cultural phenomena exemplified by the TV show Squid Game, animated movie K-Pop Demon Hunters, boy band BTS, and girl group Blackpink.

While I can credit Netflix and its huge library of Korean TV and film content for introducing me to K-drama, it was KBS World Radio and its Weekend Playlist programme on shortwave that led me to K-pop.

Early on in my holiday planning, I discovered that KBS has a public exhibition called KBS ON located in their headquarters building. Later during the trip, radio would appear unplanned in one of the other museums I hoped to explore.

Travelling to Seoul of course was a unique radio listening opportunity to hear and record stations that would otherwise require a Web SDR or internet streaming. Armed with a relatively recent copy of WRTH, I was able to compile a list of radio stations with the intention of making some short audio and video recordings.

What follows is a description of my experiences at KBS ON, some historical references to radio at the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, and notes about the radio stations I was able to hear during my stay.

All photos are my own.

The Korean Broadcasting System

The Korean Broadcasting System or KBS is the national broadcaster of Korea, providing radio, TV, and internet based content to its national audience. KBS World is the outward facing arm of the organisation providing similar services to an international audience.

The headquarter buildings of KBS are located in Yeouido, an area of Seoul that also hosts Korea’s National Assembly Building. Technically a river island, Yeouido is bordered by the Han River, offering spectacular views of central Seoul and a skyline familiar to K-drama fans everywhere.

The main KBS building is a short walk from Yeouido station on Line 5 and Line 9 of the Seoul metro system. Your route takes you through Yeouido Park where you can see a preserved Douglas C-47 cargo plane dating from the Korean War.

The main building sits along side several other KBS related areas including the KBS Hall and KBS Art Hall. Even to the untrained eye, it’s obvious that the facility is communications related with a prominent red and white antenna tower on the main building, with red scaffolding on an adjacent block housing another tower and communication dishes.

Other notable locations at the site include a roadway and building entrance where K-pop idol groups arrive every Friday to record Music Bank, a programme that showcases the latest hits of the music genre. This photo opportunity is so popular with fans that it has a dedicated playlist on the KBS World English YouTube channel.

KBS ON Exhibition Hall

The KBS ON Mural featuring the mascot Kong

The KBS ON exhibition is part of a range of locations promoted by the official visitor guide to Seoul, details of which can be found here.

Accessing the exhibition is through distinctive blue bordered doors into a large reception area. The exhibition proper then begins at the top of a short flight of stairs.

Although all sections of the tour are in Korean, section overviews are also provided in other languages. QR codes link to audio commentaries to provide the remaining explanations for non-Korean visitors.

The audio commentary supports the following languages:

- Korean

- English

- Simplified Chinese

- Japanese

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Vietnamese

- Spanish

The tour proceeds through a series of linked sections and topics which are described below.

KBS History

This section is comprised of information panels outlining the origins of KBS. Originally known as the Gyeongseong Broadcasting Station (callsign JODK) beginning in 1927, the name KBS emerges in 1945 following the liberation of Korea from Japan. KBS was established as a public broadcaster in 1973.

On Air

Through a series of large screens, this section describes the various channels KBS provides including terrestrial TV, international radio, cable, and Digital Multimedia Broadcasting, a radio transmission technology developed in South Korea.

Current Affairs / Culture programme

As a public broadcaster, this section highlights the current affairs and educational output of KBS.

Virtual Studio

This interactive section demonstrates the familiar ‘blue screen’ or chroma key technology used in news and weather forecasts. Visitors are encouraged to present their own Korean weather forecast!

Drama

The visitor is treated to a display of props and magnificent costumes from Korean period dramas, with panels and displays highlighting the role of KBS in driving growth in the K-drama industry.

Props and Costumes

Entertainment programme

Supported by large screens, this area showcases a range of local programming including talent and variety shows.

Music Bank

While the shows in the previous sections will be unfamiliar to most, Music Bank is more well known to overseas fans of K-pop. This high profile programme features live performances every Friday evening from the big names of the genre with a lottery system for fans to attend recordings.

Vertigo

This section demonstrates AI based technology developed by KBS to allow a single fixed camera to track individual members of an idol group simultaneously as they sing and dance on stage. Previously, these so-called ‘fancam’ shots required a separate camera for each performer incurring extra costs and logistics problems.

Examples of Vertigo in action are shown on large screens, featuring performances by girl groups STAYC and Illit.

Visitors can step on to a virtual stage adjacent to the displays where a single camera will automatically track your face and body without physically moving. Continue reading →

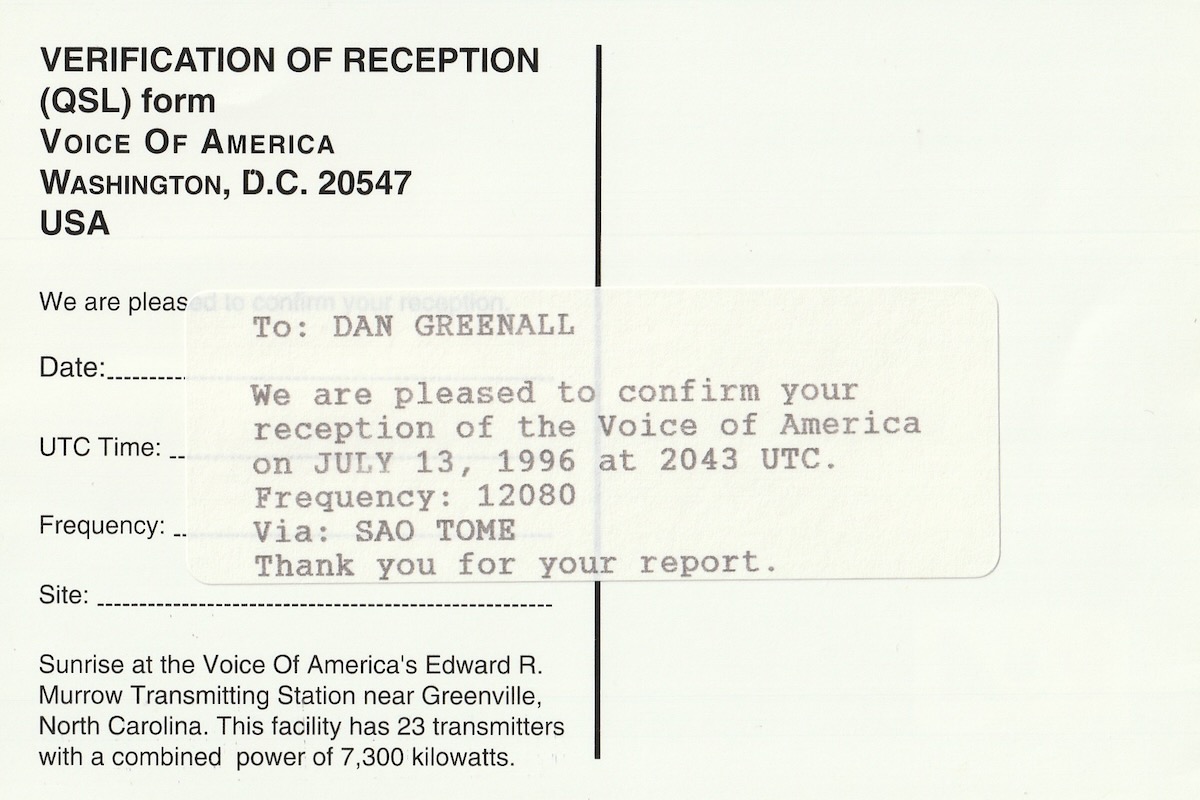

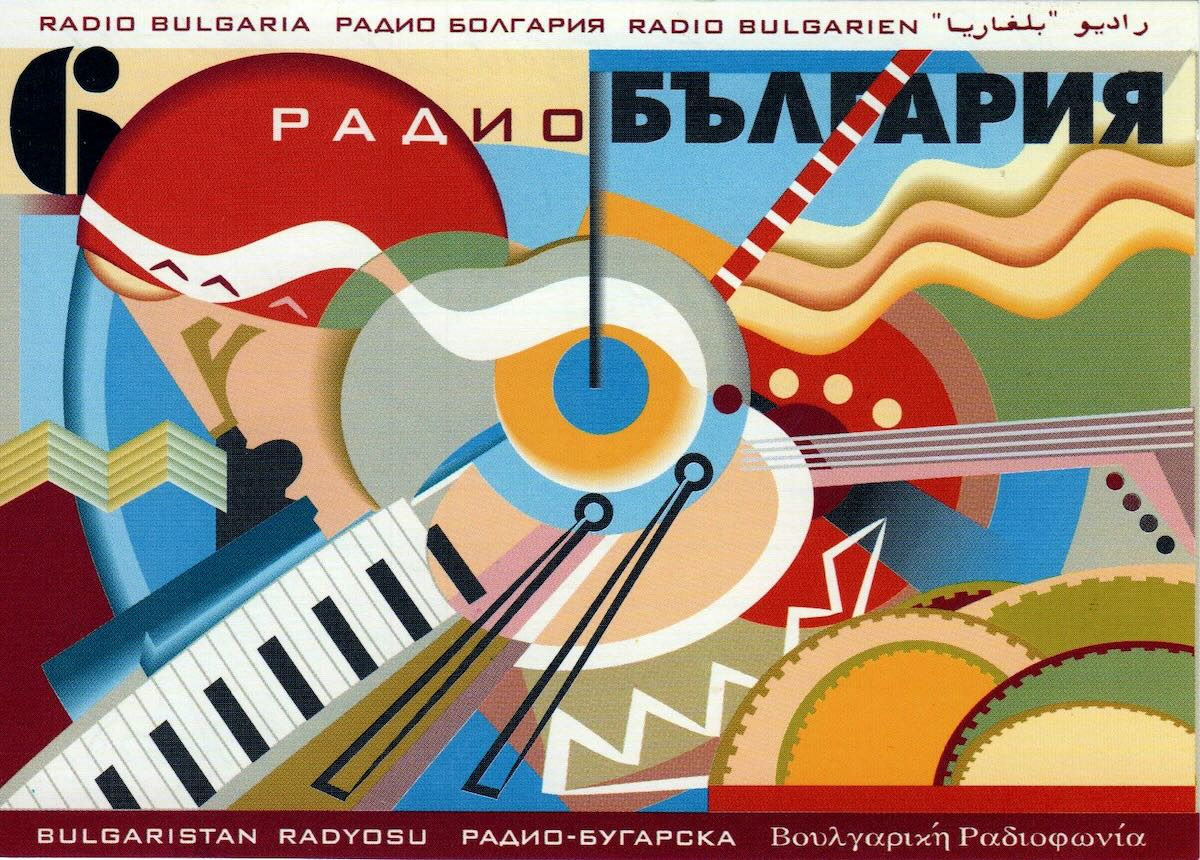

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Paul Jamet, who shares the following update and QSL card images related to Bulgarian National Radio (BNR) and Radio Bulgaria.

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Paul Jamet, who shares the following update and QSL card images related to Bulgarian National Radio (BNR) and Radio Bulgaria.