Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Dennis Dura, who shares this CE Outlook article examining the trend of major automakers removing AM/FM radios from new vehicles and what it means for the 12-volt ecosystem. With AM/FM being increasingly omitted in favor of digital monthly subscriptions and mobile-connected audio services, this article explores the implications for listeners, aftermarket options, and the broader impact on radio accessibility in cars. Read more here: https://www.ceoutlook.com/2026/01/15/car-makers-remove-am-fm-what-it-means-for-12-volt/

Category Archives: AM

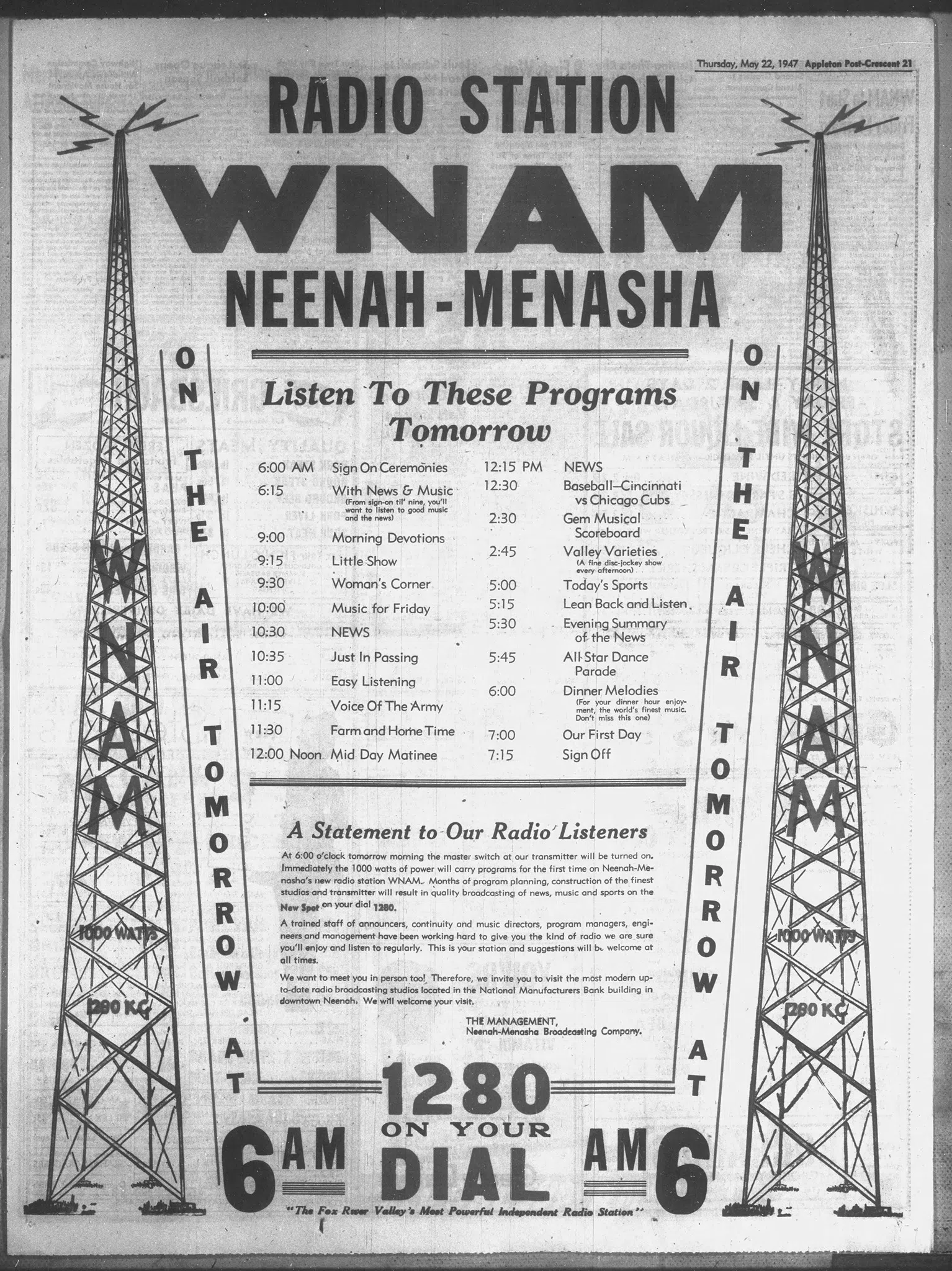

WNAM Final Broadcast and DX Test Announcement: December 30-31, 2025

The following announcement was shared by Loyd Van Horn of DX Central:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

1280 – WNAM DX Test Announcement

Dec 27, 2025

The Courtesy Program Committee (CPC) of the National Radio Club (NRC) and the International Radio Club of America (IRCA) announces a special DX Test for distant listeners for radio station WNAM on 1280 kHz in Neenah-Menasha,WI. The test is scheduled for Tuesday, December 30th and Wednesday, December 31st starting at Midnight local Central Standard Time through 5:05 AM Central Standard Time (This equates to 0600 to 1105 UTC on 30 December and 31 December).

This test is scheduled to run for 2 minutes after ABC News at the top-of-the-hour each hour from Midnight to 5am local Central time. ABC News runs from :00-:03 after the hour. The DX Test will run from :03-:05 after the hour, each hour of the window.

These test transmissions are being broadcast in conjunction with the final days of broadcast of WNAM. WNAM is scheduled to cease broadcast operations at 11:59 PM Central Time on December 31st.

These test transmissions are a way to honor the history of WNAM in its service to the community as well as provide an opportunity for DXers to hear WNAM one last time – or possibly the first time!

The test will consist of an assortment of classic station jingles, sweep tones, voice IDs, morse code and other sounds.

WNAM will be operating at their daytime power/pattern for the duration of the test events.

In addition, listeners/DXers are invited to tune in WNAM’s special 3-hour farewell broadcast on Wednesday, December 31, starting at 9:00 PM Central Standard Time. This will include a “recreation” of the station’s glory years as “Blue 128” complete with airchecks from previous on-air staff.

RECEPTION REPORTS & QSL REQUESTS

All reception reports will be verified through the station directly with a special QSL that was developed for the occasion. Reception reports along with MP3 recordings or .MP4 video recordings of your reception should be emailed to:

[email protected]. Please be sure to use the subject line: “WNAM 1280 DX TEST RECEPTION REPORT.”

The following are recommendations are in effect in order to expedite processing and receive a QSL verifying your report:

-

- Reports via email only – this is required. An MP3 file attachment of your reception (best reception) or an MP4 video clip are preferred. While written descriptions will be considered along with the recording, they may not suffice alone for verification.

- Reports must be submitted within 30 days of the test.

- The report must include your name, location, and return email address, clearly grouped together at the top of the verification request.

- Please also include a description of your receiver, antenna, and any interference noted.

- If you use a remote SDR to receive the test, you must clearly indicate that in your verification request. We will only accept one such report per DX’er. You cannot log the test on multiple remote SDRs and request multiple verifications.

The IRCA/NRC CPC would like to thank the owners and staff of WNAM}, Steve Edwards and CPC member Loyd Van Horn for helping to arrange the test.

Good luck to all DXers!

About the CPC

The Courtesy Program Committee (CPC) is a cross-functional group comprised of members of both the National Radio Club (NRC) and International Radio Club of America (IRCA) for the purpose of coordinating and arranging DX Tests with AM radio stations. These DX tests both allow radio stations to conduct valuable equipment tests on their transmitter and audio chain as well as enable DX hobbyists to receive the testing station from greater distances than would normally be possible. The CPC membership consists of: Chairman Les Rayburn, Paul Walker, George Santulli, Joe Miller and Loyd Van Horn.

For radio stations interested in coordinating a DX test with the CPC, please visit the following Web site for more information:

https://amdxtest.blogspot.com/

For more information on the types of content heard during a DX test, the video “An introduction to DX Tests” is available at DX Central:

Check Your Time with the LM Chime

by Dan Greenall

Shades of the 1970’s. Commercial AM radio (in English) the way it used to be. Heavy on nostalgic music from the 1960’s to the 1990’s, plenty of good old style jingles, and of course, the LM chime every hour.

Decades ago, the “LM” used to stand for Lourenco Marques Radio as the station was based in this city in Mozambique. Today, it is Lifetime Memories Radio, and broadcasts to Maputo and the surrounding area, where it can be heard on 87.8 FM. The station also broadcasts on 702 kHz medium wave from a transmitter near Johannesburg, South Africa, and can be heard worldwide via Kiwi SDR or online stream here https://lmradio.co.za/

Decades ago, the “LM” used to stand for Lourenco Marques Radio as the station was based in this city in Mozambique. Today, it is Lifetime Memories Radio, and broadcasts to Maputo and the surrounding area, where it can be heard on 87.8 FM. The station also broadcasts on 702 kHz medium wave from a transmitter near Johannesburg, South Africa, and can be heard worldwide via Kiwi SDR or online stream here https://lmradio.co.za/

In addition to the live stream, be sure to read about the rich history of the station that began in 1936. The station was shut down in 1975 when Mozambique gained independence, but has re-emerged in the 21st century. A visit to the LM Radio museum is well worth the trip. https://lmradio.co.mz/history/

In 1973, I was able to hear Radio Clube de Mocambique on 4855 kHz shortwave from here in Canada. If you listen closely, you can hear the LM chime.

In 1973, I was able to hear Radio Clube de Mocambique on 4855 kHz shortwave from here in Canada. If you listen closely, you can hear the LM chime.

Give them a listen, but first, check out these sample recordings made between November 27 and December 8, 2025, through a Kiwi SDR located near Johannesburg:

2025-11-27:

2025-11-28:

2025-11-28:

2025-11-29:

2025-12-04:

2025-12-08:

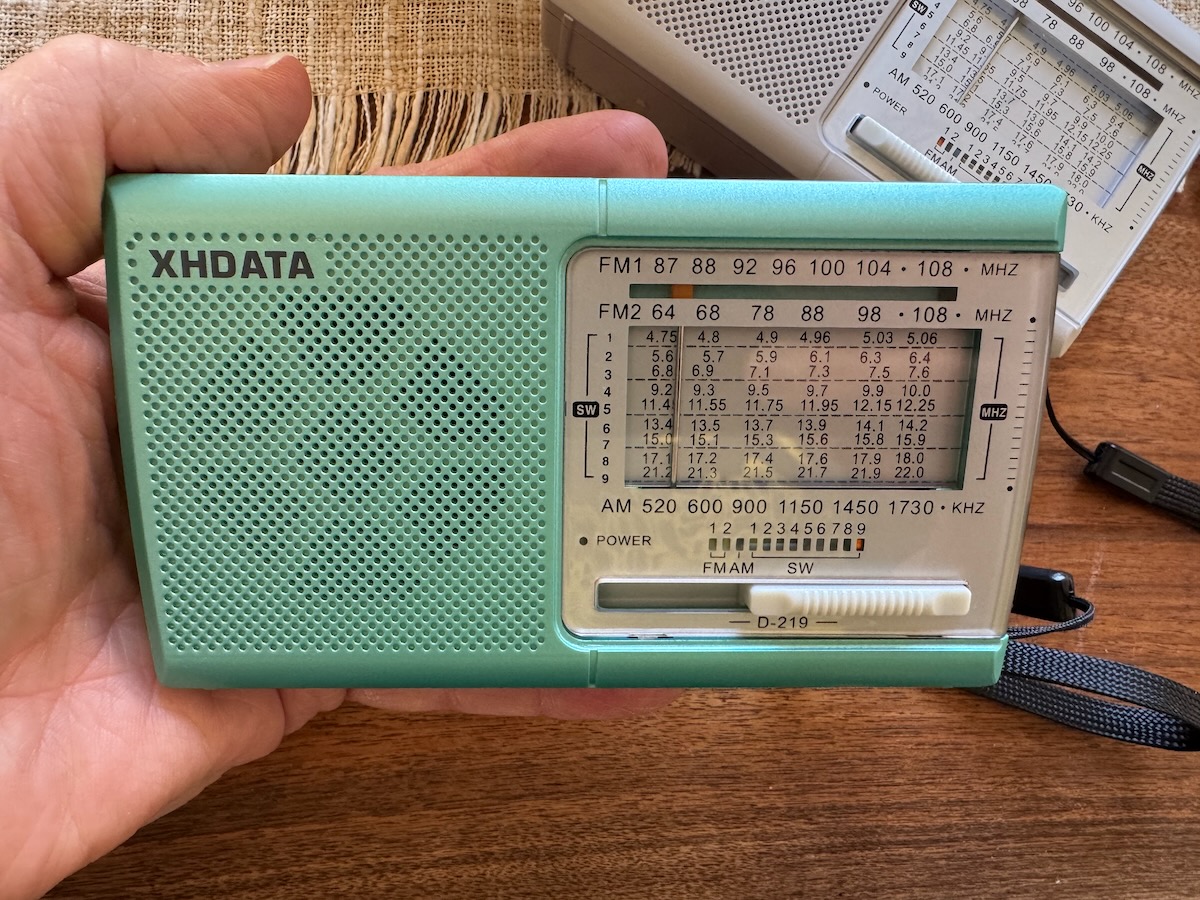

Rediscovering Simple Radio Joy with the XHDATA D-219

It’s been a long while since I’ve written a receiver review. Years ago, I cranked them out several times a year and genuinely loved the process–evaluating performance, quirks, economics, and overall user experience. Writing reviews is, to this day, one of my favorite things to do.

But over the past four years, my reviewing work shifted more toward amateur radio and portable operations, especially as my QRP activities ramped up. And as many of you know, the SWLing Post now has an incredible group of contributors who regularly write thoughtful reviews, taking some of the pressure off of me.

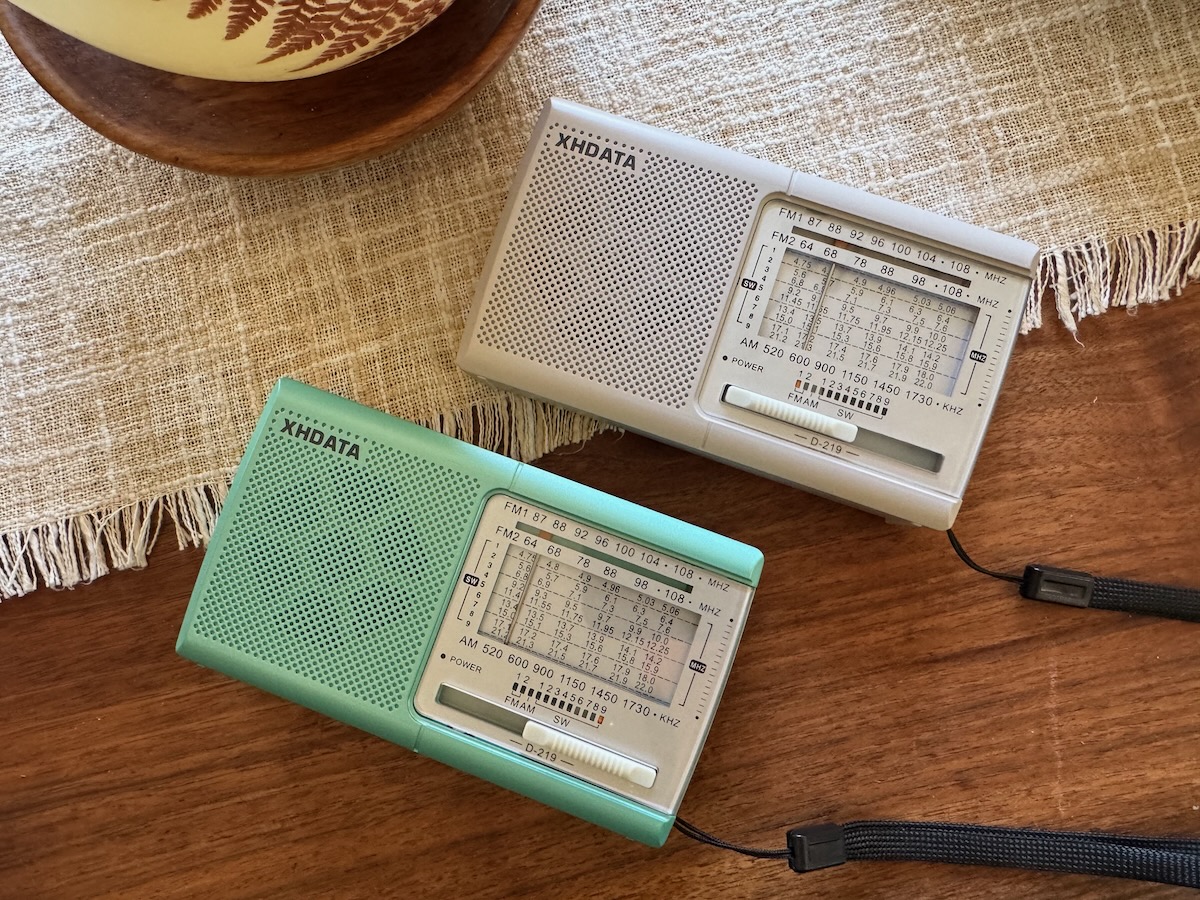

So when my contact at XHDATA reached out a few weeks ago asking if I wanted to try two new color variants of their ultra-affordable D-219, I surprised myself: instead of passing it along to one of our contributors, I decided I wanted the chance to revisit the world of simple, inexpensive portables firsthand.

Why? Because I’d been hearing surprisingly positive things about this little radio—and because it reminds me of the DX-397, a tiny analog portable I used for years after working at RadioShack right out of college.

This review, then, is less about testing a product and more about rediscovering the joy of having a simple, super-basic radio at hand.

This review, then, is less about testing a product and more about rediscovering the joy of having a simple, super-basic radio at hand.

Disclosure: XHDATA is a generous long-time sponsor of the SWLing Post. They sent both of these D-219 radios free of charge. Honestly, I don’t know many companies that would send out a sub-$20 product as a review loaner–it probably costs them more in shipping.

As always, I’ll be gifting these units back out once I’m finished. And in this case, I’ll also be buying three more myself for Christmas gifts… one of those, I’ll keep.

Design & First Impressions

Let’s be clear: the D-219 is a simple radio. It looks like something straight out of the mid-1990s, with:

Let’s be clear: the D-219 is a simple radio. It looks like something straight out of the mid-1990s, with:

- an analog tuning dial

- band-switching sliders

- a dedicated on/off switch on top

- a small, lightweight plastic enclosure

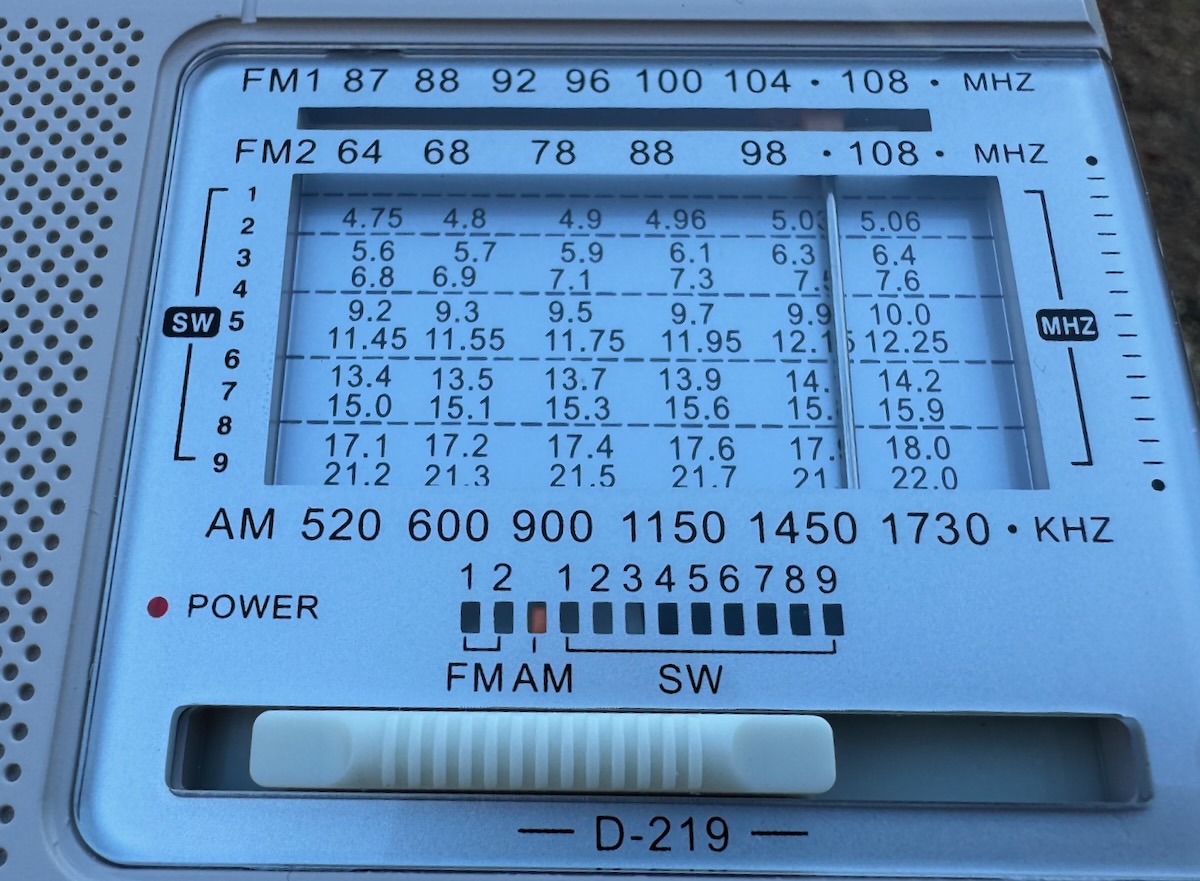

But inside, it’s very much a modern radio. The D-219 is based on the Silicon Labs Si4825-A10 DSP chip, meaning that although tuning feels analog, you’re actually listening to a DSP-based receiver stepping through the band in predetermined increments.

XHDATA sent me two new color options: off-white and light silver-green. Both look great in person.

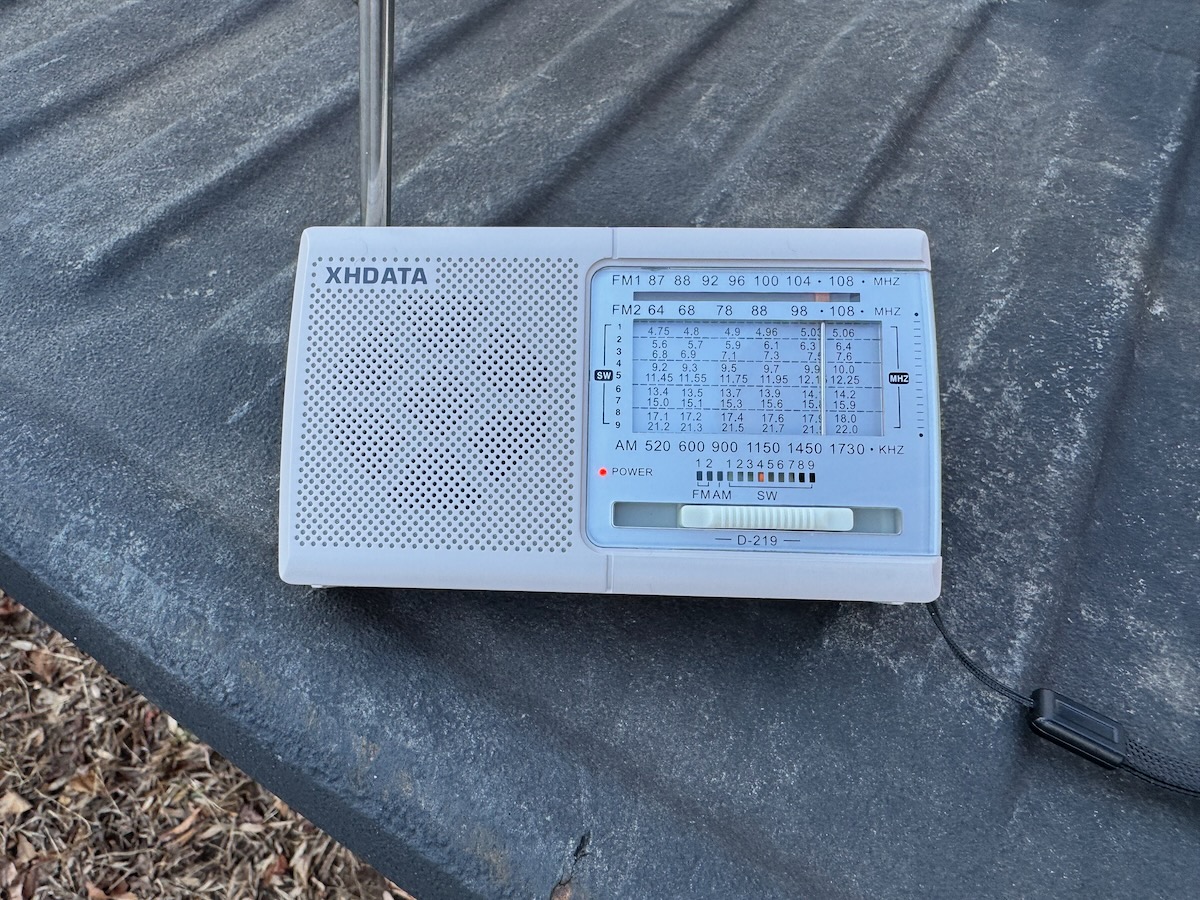

Using the D-219 Outdoors

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been doing a lot of work outside—stacking firewood, yard projects, general winter prep. The D-219 became my little companion radio during all of it.

I mostly listened to:

- Mediumwave

- A bit of shortwave

- and FM radio

Audio Quality

The audio surprised me. It’s a tiny speaker, so don’t expect brilliant fidelity, but it’s perfectly listenable and cuts through outdoor noise when the volume is up.

Performance

FM performance is excellent—far better than I expected. I have a handful of “benchmark” distant FM stations that many small portables struggle to hold onto. The D-219 locked onto them easily. DSP chips often shine in FM, and this was no exception.

FM performance is excellent—far better than I expected. I have a handful of “benchmark” distant FM stations that many small portables struggle to hold onto. The D-219 locked onto them easily. DSP chips often shine in FM, and this was no exception.

Mediumwave was the biggest surprise. I have a regional AM station–WTZQ 1600 kHz–that I enjoy during the day, especially around the holidays. Only about half of my small portables receive it well enough to be pleasant.

The D-219 locked it in better than most of my other inexpensive portables.

That alone impressed me.

Shortwave performance is quite good for the price. Sure, it lacks an adjustable filter, and tuning steps mean you don’t get that smooth, fluid band-scanning experience like a proper analog receiver. But overall, it works pretty well.

On 31 meters, for example, tuning felt natural and not cramped–something many ultra-cheap shortwave radios struggle with. It helps that the selected shortwave bands have enough tuning bandspread that you don’t have to use micro adjustments during tuning (I’m looking at you, XHDATA D-220!).

Back in the Cold War era, when the bands were jammed shoulder-to-shoulder, a radio like this would have been harder to use. But today, with fewer simultaneous signals, it’s totally workable.

Real-World Utility

In the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, I’ve become even more vocal about keeping at least one AM/FM/SW radio as part of your personal preparedness kit. The D-219 checks many boxes:

In the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, I’ve become even more vocal about keeping at least one AM/FM/SW radio as part of your personal preparedness kit. The D-219 checks many boxes:

- Runs on AA batteries

- Very low power draw

- Lightweight and pocketable

- Small enough to disappear into a backpack or glove compartment

I’ve been using mine heavily for two weeks on a pair of Eneloop rechargeables and haven’t had to recharge yet.

Two of the D-219s I’m buying will be stocking stuffers for my daughters, just so they always have a reliable source of news and info while at university–even if the power or internet goes down.

Two of the D-219s I’m buying will be stocking stuffers for my daughters, just so they always have a reliable source of news and info while at university–even if the power or internet goes down.

Why This Radio Works

I’m sure own more than three dozen portable radios here at SWLing Post HQ—from high-end benchmarks to tiny ultralights. Normally, I advocate for buying a good-quality receiver instead of “throwaway” electronics.

But I don’t think the D-219 is a “throwaway” radio; being based on the Silicon Labs DSP architecture, it doesn’t have an insane component density–inside, its board is almost roomy. Looking at it, I think I could make modest repairs myself as long as the chip still functions.

Sometimes simple designs translate into long life rather than an early landfill destiny. Of course, only time will tell, and I will post an update if my radio experiences any issues.

This is why I’m comfortable giving them to my daughters as everyday radios. And frankly, I’d much rather they lose or break a $13 D-219 than my old Panasonic RF-65B, PL-660, or ICF-SW7600GR–some of my most cherished (and irreplaceable) legacy portables.

The D-219 is also a perfect glove box radio. One to grab and listen to when you’re waiting on your spouse/partner to finish a yoga class, or waiting on your kids at schoool.

In Summary

If you’re looking for a true benchmark portable, obviously, this isn’t it.

If you’re looking for a true benchmark portable, obviously, this isn’t it.

But if you want:

- a fun, capable, ultra-affordable little radio

- something to give as a holiday stocking stuffer

- a simple preparedness radio that uses AA batteries

- a pocketable MW/FM/SW companion

- a “leave-it-in-the-car” radio

…the XHDATA D-219 genuinely delivers for well under $20 each.

And as someone who hates e-waste and often avoids ultra-cheap electronics, I’m betting this radio will age better than most. Its internal design is refreshingly simple and built around the reliable Si4825-A10 DSP chip. There just isn’t much inside to fail.

For the price, performance, and sheer fun factor? The D-219 is a solid option.

Purchase options:

- Buy directly from XHDATA

- Purchase from Amazon.com (note: this affiliate link supports the SWLing Post)

Giuseppe’s Clever Homebrew Ferrite Antenna for MW and SW Listening

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Giuseppe Morlè, who writes:

Dear Thomas,

I’m Giuseppe Morlè, IZ0GZW, from Formia in central Italy on the Tyrrhenian Sea.

This is one of my builds from a few years ago: the T Ferrite antenna. It’s a minimal antenna designed mainly for mediumwave, but it also performs well on shortwave.

Inside the tube at the top are two 12 cm ferrite rods with 32 turns of telephone wire wrapped around them—this section is for mediumwave. Then, on the outside of the tube, I added four more turns for shortwave. A variable capacitor of about 1000 pF completes the circuit.

Shortwave is activated with an alligator clip. When the clip is removed, only the mediumwave section is active.

I tested this antenna with my old Trio 9R-59DS from the 1970s—a tube receiver still in perfect condition. To my pleasant surprise, the receiver paired beautifully with the antenna.

These tests were done on mediumwave in the early afternoon yesterday while it was still light outside. With the antenna placed above the receiver inside my shack, I was able to receive stations from across the Mediterranean basin and Eastern Europe, even in areas where the sun had already set. I really enjoy testing this antenna before evening, and I’m very satisfied with its performance.

You can see the results in this video on my YouTube channel:

I hope this will be of interest to the friends in the SWLing Post community.

Best regards to you and to all,

Giuseppe Morlè, IZ0GZW

We always enjoy checking out your homebrew antenna designs, Giuseppe! Thank you!

Carlos Tunes Into an Earthquake Alert on NHK

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Carlos Latuff, who writes:

I was listening to the news on the radio when I was caught by surprise with this earthquake alert!

NHK earthquake alert, listened in Porto Alegre, Nov 25, 2025, 09h09 UTC:

Configuring the “News Cruiser” for your emergency radio

Rob, W4ZNG, endured three weeks without electricity on the Mississippi Gulf Coast as a result of Hurricane Katrina.

When he and I spoke about his experience (and what any one of us might want in our “fertilizer hits the fan” radio kit), he mentioned that during Katrina, all of the local broadcasters were wiped out. There was a local low-power FM broadcaster who got permission to increase power to 1,000 watts and was broadcasting where to get food and water. There was a New Orleans AM station that was on the air, but all of its coverage was “New Orleans-centric.” After a few days, some local FM broadcasters, working together, cobbled together a station that they put on the air and began broadcasting news. Rob also began DXing AM stations at night to get additional news.

Hold that thought for a moment.

A few weeks ago, Andy, W2SRA, pops up on the Radio Monitoring Net (which I run on Tuesday nights) with a list of “Rolling News” medium wave stations that can be heard at least some of the time from my location in the Capital District of New York State. Rolling news stations broadcast news ‘round the clock.

The list includes:

- 780, WBM, Chicago, IL

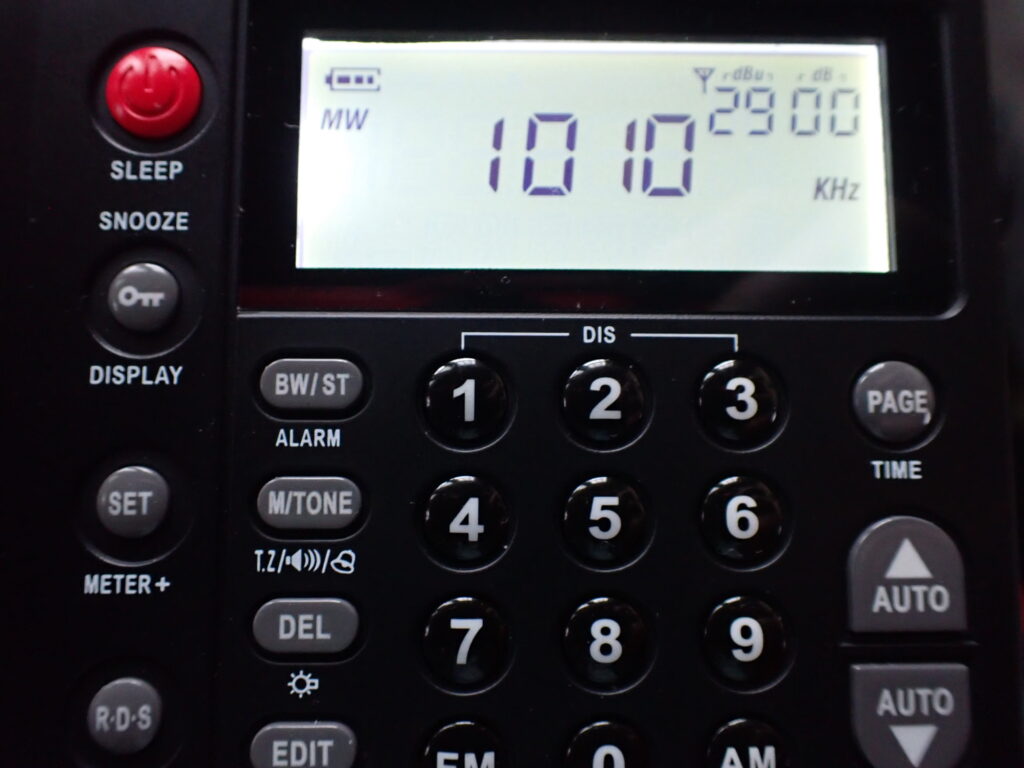

- 1010, WINS, New York City

- 1030, WBZ, Boston, MA

- 1060, KYW, Philadelphia, PA

- 1090, WBAL, Baltimore, MD

- 1130, WBBR, New York City

- 1500, WFED, Washington, DC

When I saw that list, I thought “This is a pretty good resource.”

Then a day ago, something clicked, the lightbulb went on, and I realized: “This is exactly the list of stations that I would want if I were in the same situation as Rob after Katrina, where my local stations were dark, and I wanted to know what was going on! I named the list: the News Cruiser.

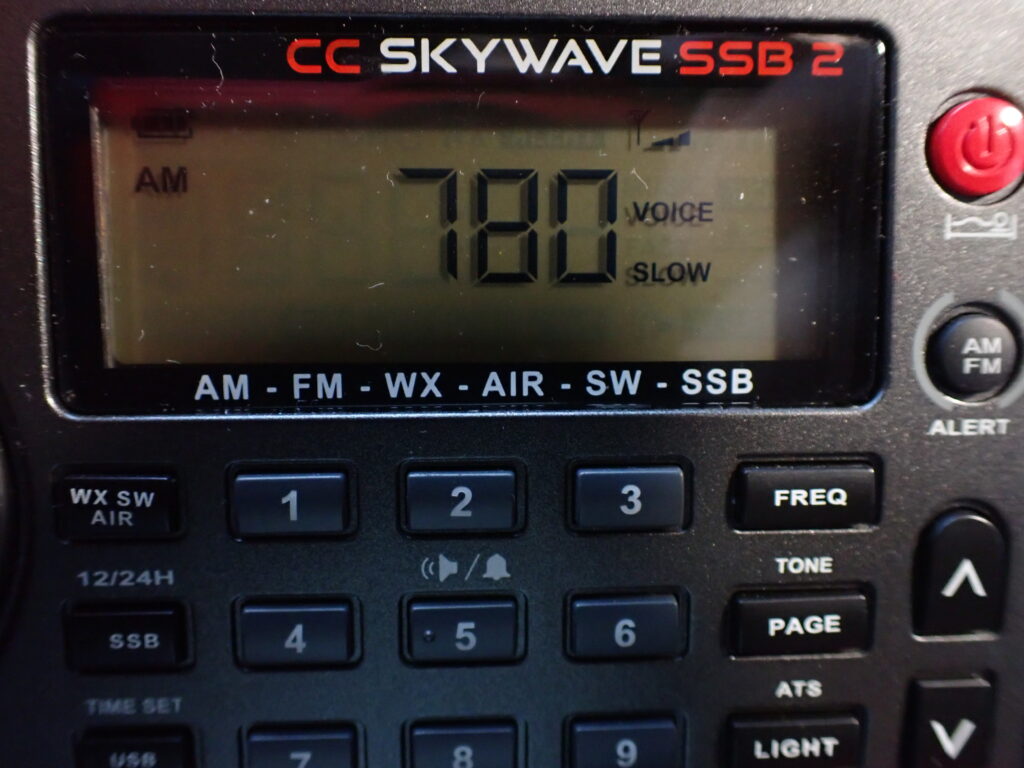

So, in the predawn hours, I decided to put the News Cruiser list to the test. I plugged the frequencies into several of my radios, and here is what I found. With the CCrane Skywave SSB 2, the signals ranged from copyable with noise to marginal to uncopyable, depending on the station. With the CCrane CCRadio SolarBT the results were better, but often tough to copy. Neither of these radios has the ability to connect to a medium wave loop antenna through a direct wired connection, although they can be inductively coupled to a loop such as the Terk AM Advantage.

The CCrane 2E, a much bigger radio with a much bigger internal ferrite bar antenna, produced markedly improved results. All three of these radios can be powered by off-the-shelf AA or D cells, which I considered to be an advantage during an emergency.

Two other radios, the Qodosen DX-286 and the Deepelec DP-666, which are powered by rechargeable batteries, acquitted themselves quite well when hardwired to the Terk AM Advantage loop antenna, but I prefer radios that can accept off-the-shelf commercial batteries.

If you live in North America, you can create your own News Cruiser list for your emergency radio by consulting https://radio-locator.com/ and using the search function to find stations that broadcast in the “News” format.

Once you have assembled your list, test it out with the radio you would grab in an emergency and see how well they perform. You might find the perfect combination that you like or you might discover that there is some room for improvement.

In any event, I heartily recommend that every household has an emergency radio that can be easily deployed to discover essential information when the fertilizer hits the fan. The point is to discover what works for you and to discover it before it is needed.

Further, I would very much like to know what works for you no matter where in the world you are located. Let me know in the comments below.