Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Dan Greenall, who shares the following guest post:

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor Dan Greenall, who shares the following guest post:

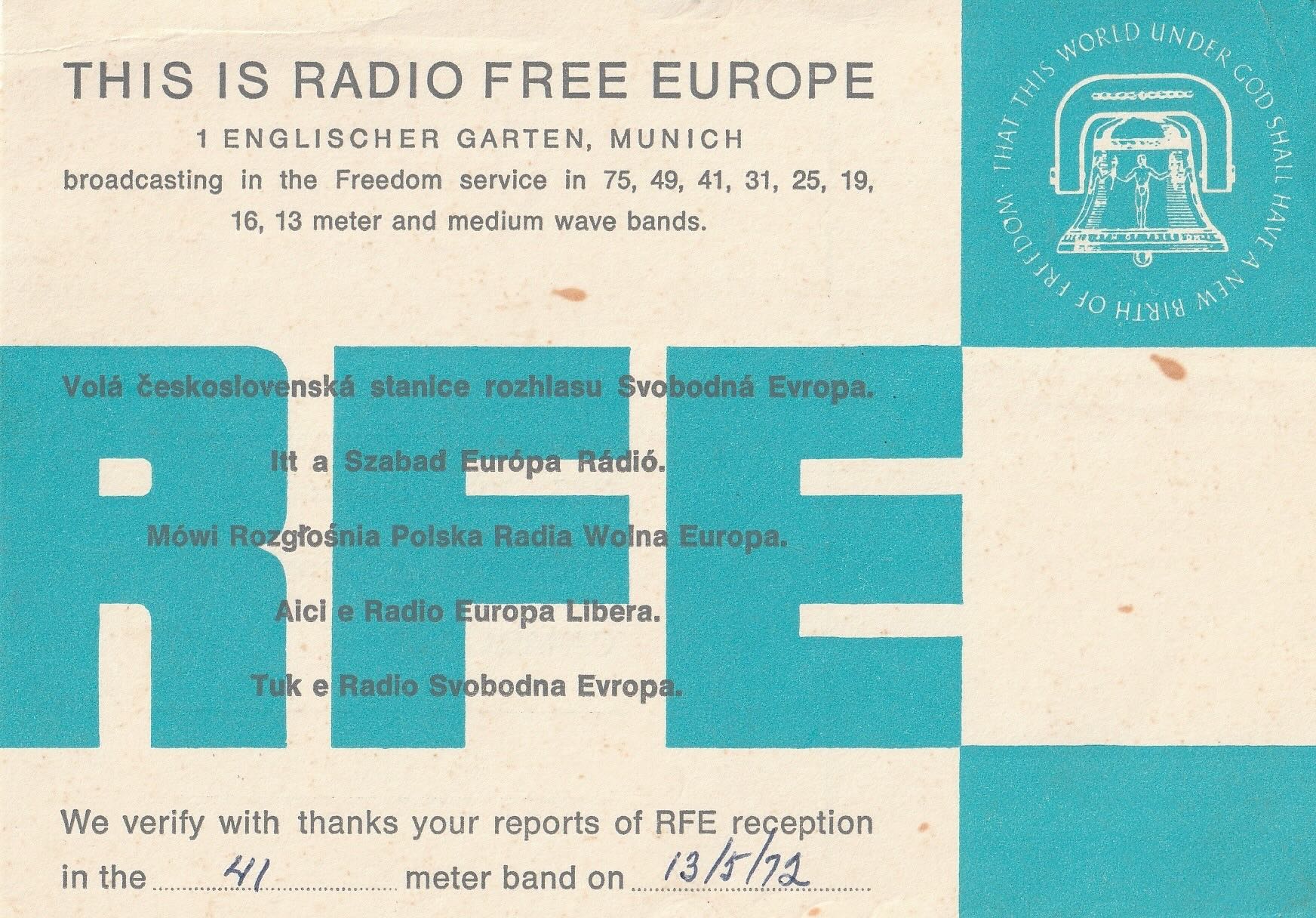

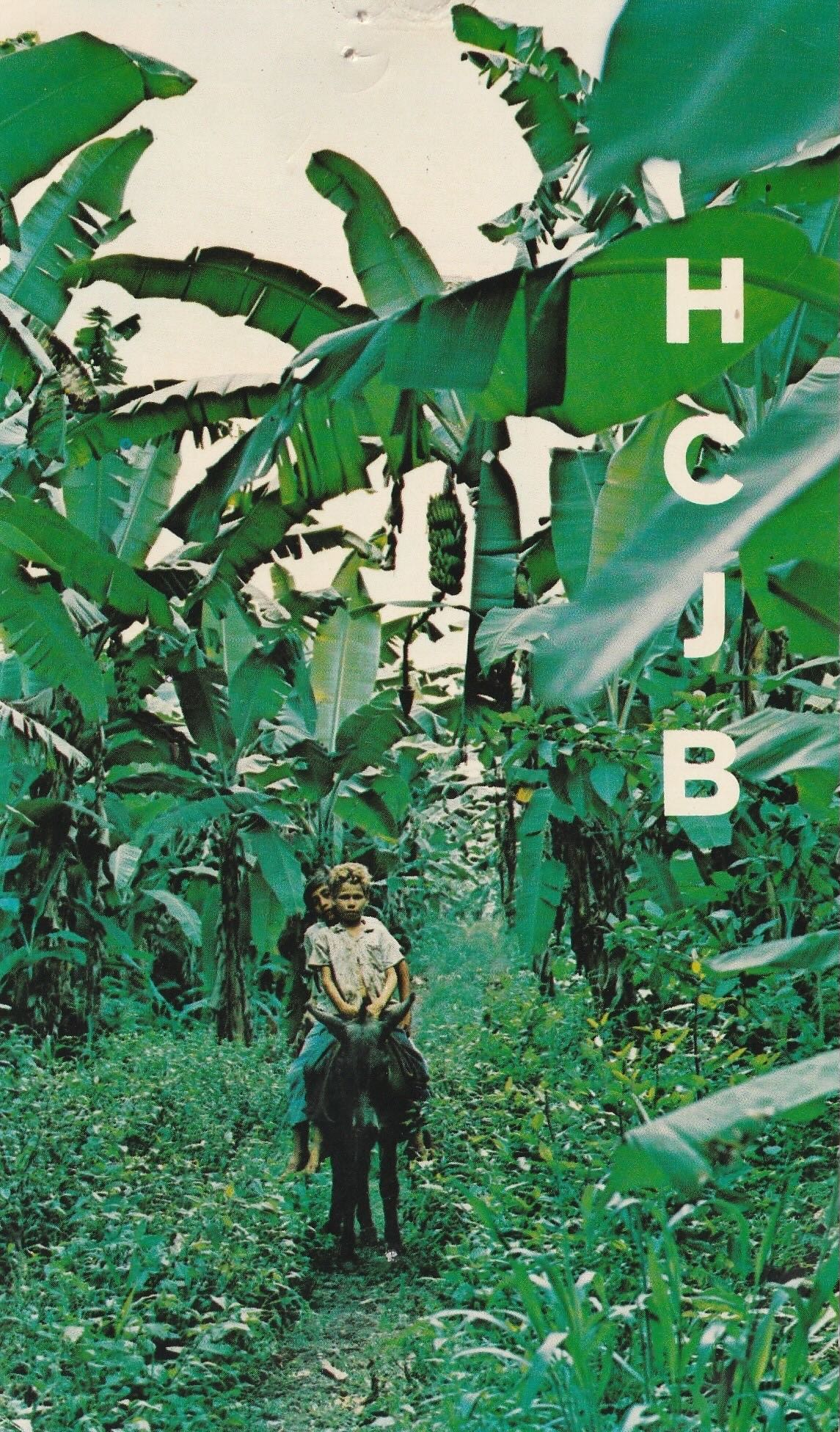

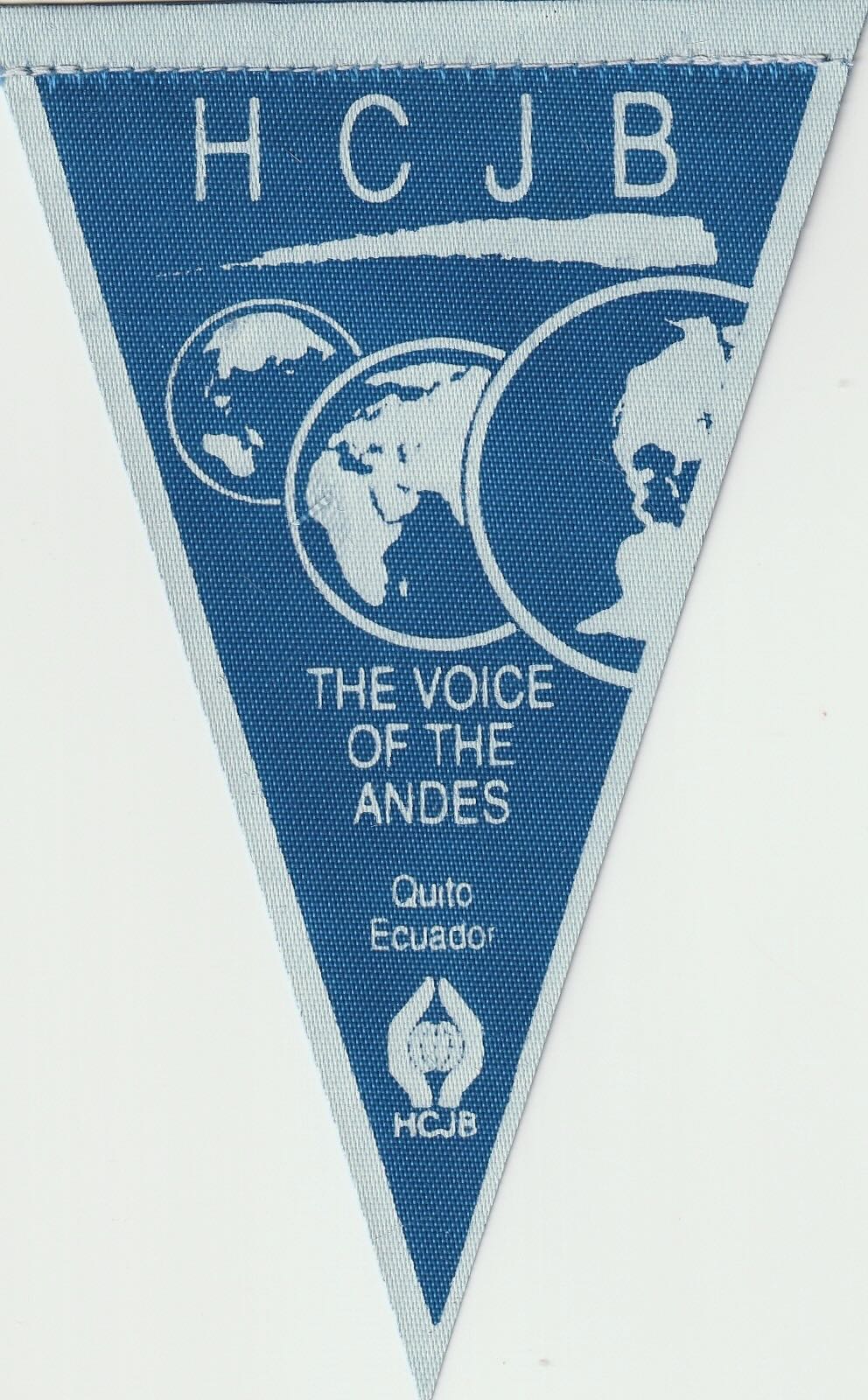

Europe on shortwave in the 1970’s

by Dan Greenall

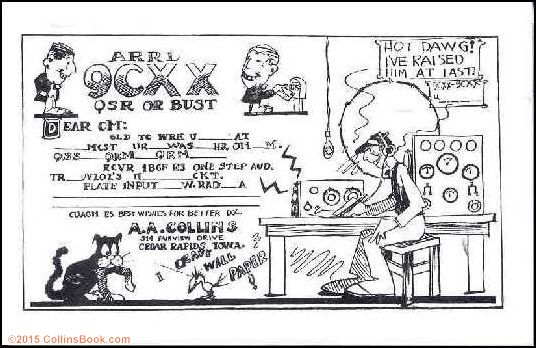

During the golden years of shortwave listening, many European countries had an international shortwave service and broadcast programs to North America (where I live) in English. As a result, these stations were usually among the first that a newcomer to the hobby would find. However, since there was no internet or e-mail, schedules often had to be found in the various club bulletins and hobby magazines. QSLs arrived through the postal system and could often take months to arrive.

I soon developed the habit of making a brief recording of each station as additional “proof of reception,” and many of these have survived to this day. These were typically made by placing the microphone directly in front of the speaker of my receiver. In recent years, they have been uploaded to the Internet Archive, and links to some of them from the early 1970s can be found here.

[Note that each title links to the Archive.org page where you can find more information and QSLs.]