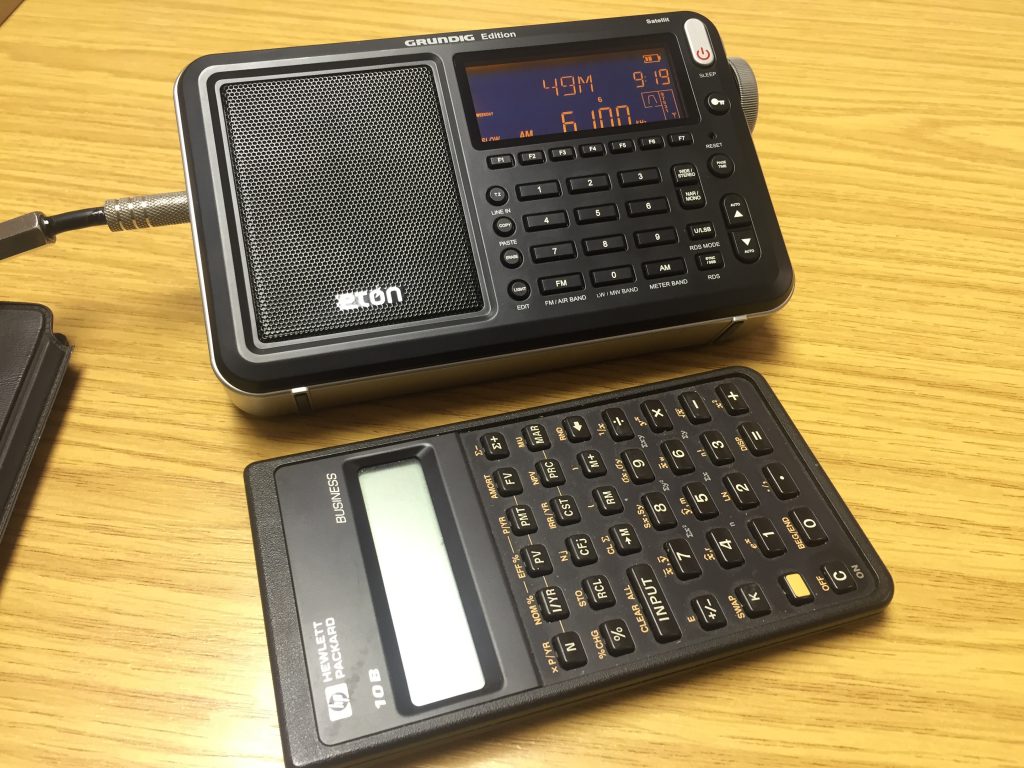

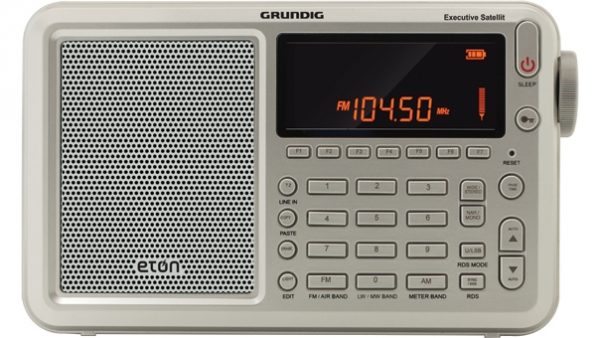

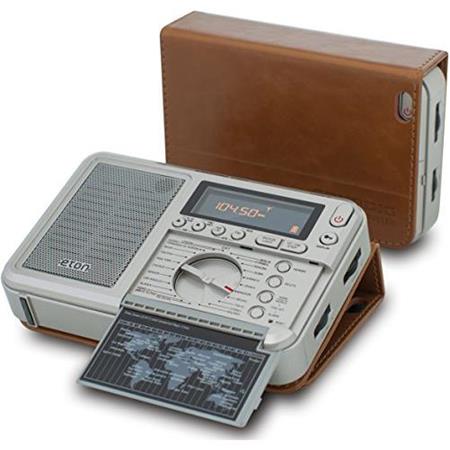

Hi there, it’s been about three weeks now since I started DXing with the Eton Satellit and I thought it time to post an updated review, based on my experiences thus far, along with some recent catches. Noting that other radio hobbyists with a strong presence online have been posting neutral to negative reviews on this receiver, I would just like to point out, perhaps rather obviously, that no receiver is perfect and just as importantly, the criteria on which a portable radio is judged will be different from user to user, based on their listening habits. I am almost exclusively engaged in DXing with the Satellit, whilst others will be listening on the broadcast bands on a more casual basis. I know that for some, the ultimate quality and finish of a product is as important as performance and they would make their physical assessment in a very detailed manner. I on the other hand focus mainly on performance and as regards quality, I’m reasonably satisfied if it doesn’t fall apart in my hands, straight out of the box! That actually happened – and it’s sort of where I draw the line 🙂 I guess the point is, I try to respect everyone’s opinion, irrespective as to whether we are in agreement or not and I believe that’s healthy for the future of our hobby.

Ok, back to the Satellit. Firstly, I am able to confirm that in terms of ultimate sensitivity, this portable is very close to my Sony ICF-2001D – one of the most highly regarded portables ever made. The delta in performance between the two is most perceptible on the weakest of fading signals that intermittently deliver audio with the Sony, but can’t be heard on the Eton. On stronger signals, my experience is that either radio might provide the strongest and or highest fidelity audio. I have a series of comparison videos already in the can, which will be uploaded to the Oxford Shortwave Log YouTube channel soon.

In terms of selectivity, the digital bandwidth filters work very well, although I note that even on the narrowest setting (2 kHz) when operating in a crowded band, adjacent channel QRM can occasionally still sound quite pronounced, as compared to my Sony ICF-SW55 or ICF-2001D receivers. As regards synchronous detection, this is more of a hit-and-miss affair. Subscribers to my channel might notice that in nearly all of my reception videos featuring the Eton Satellit, I have not engaged the SYNC. That isn’t to say it doesn’t work, however, even with selectable sidebands, the SYNC mode often appears to increase the overall signal amplitude and noise floor, without positively influencing the SNR. However, it’s interesting to note that signals on the Satellit in AM mode often almost match the ICF-2001D in SYNC mode, in terms of overall SNR. More on that to come.

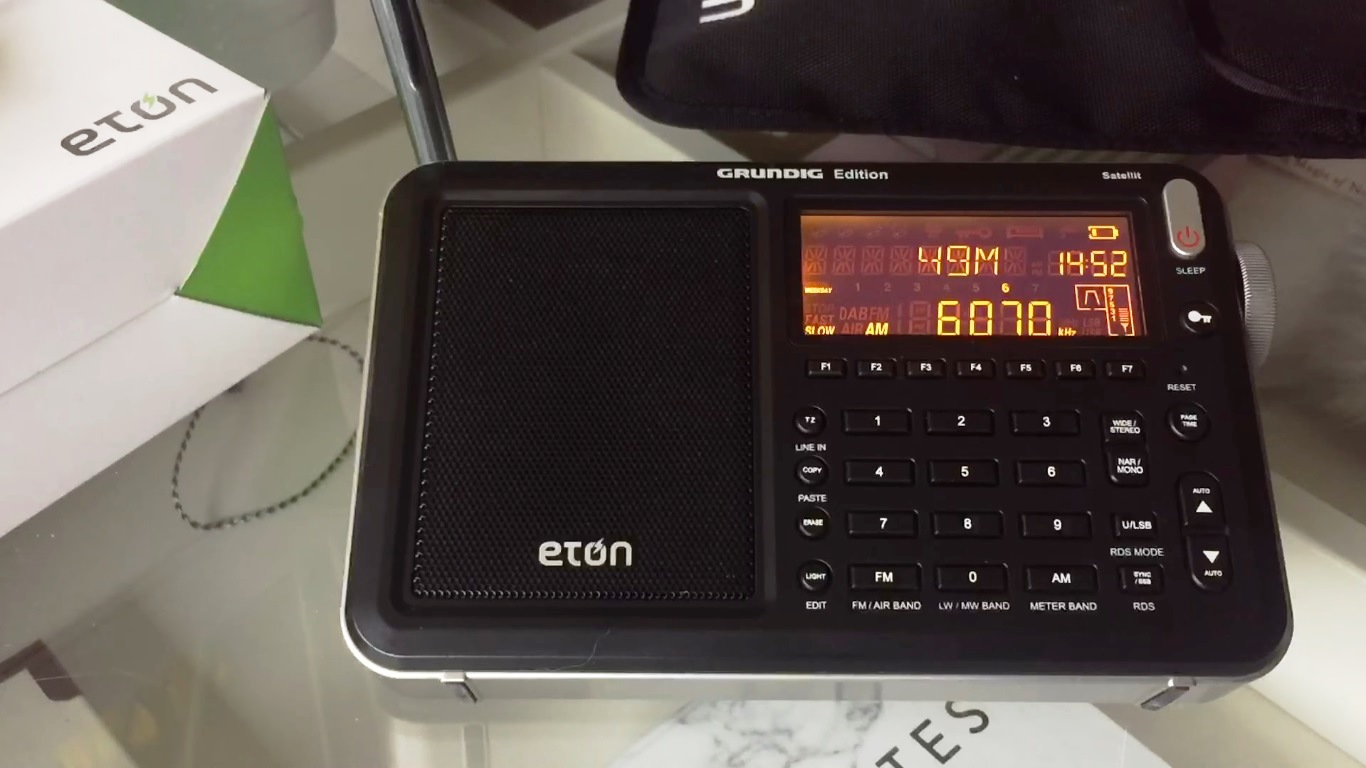

There are a number of ways to tune the radio; manually using the tuning knob (and this has a decent feel/ resistance to it), direct frequency input which requires pressing the ‘AM’ button to engage, automatic search and access to 700 memory locations, via 100 screen pages. In the real world – and by that I mean ‘my world’ which is most often in the middle of a field, or the woods, all of the above tuning options are as ergonomic as most of my other portables. With regard to SSB reception, there are fast, slow and fine tuning options with a maximum resolution of 10 Hz and this works very well to reproduce natural sounding speech in LSB and USB modes. The tuning speed/fine options are engaged by pressing the tuning knob inwards towards the set – quite a neat idea. With SSB and SYNC there’s always a little pause whilst the electronics engage – a set of chevrons appear on the screen to indicate the receiver is actually doing something. It’s similar to the Sony ICF-SW77 where you effectively toggle between SYNC USB and LSB and wait for lock. Not an issue for me, but it might annoy some, particularly those who have experience with the ICF-2001D, where SYNC engagement is instantaneous, if the signal is of sufficient strength. A small point, but worth making.

So, overall, a brilliant little radio that in my opinion is completely worthy of the ‘Satellit’ branding, at least in terms of ultimate performance. As I mentioned previously, one of the most experienced DXers I know, with more than 3 decades of listening to the HF bands and an owner of a number of vintage Satellit receivers noted that the Eton Satellit outperformed them – and by some margin. To further demonstrate this, I have included links to recent reception videos. In particular, I copied three of the regional AIR stations with signal strength and clarity that had never previously been obtained. I also copied HM01, the Cuban Numbers Station for the first time on the 11 metre broadcast band, Sudan and Guinea on the 31 metre broadcast band (a whopping signal from Guinea) and Polski Radio 1 on longwave. I hope you find them interesting. Since featuring the Satellit on my channel, one of two of my subscribers have purchased this radio and thus far have been very happy indeed with it’s performance.

Ultimately, I have to strongly recommend this portable to anyone interested in DXing and in particular those that embark on DXpeditions. I just hope that should you decide to buy one, you receive an example that performs was well as mine. Embedded reception videos and text links follow below, In the mean time and until my next post, I wish you all great DX!

Click here to watch on YouTube

Clint Gouveia is the author of this post and a regular contributor to the SWLing Post. Clint actively publishes videos of his shortwave radio excursions on his YouTube channel: Oxford Shortwave Log. Clint is based in Oxfordshire, England.