Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, DanH, who shares the following guest post:

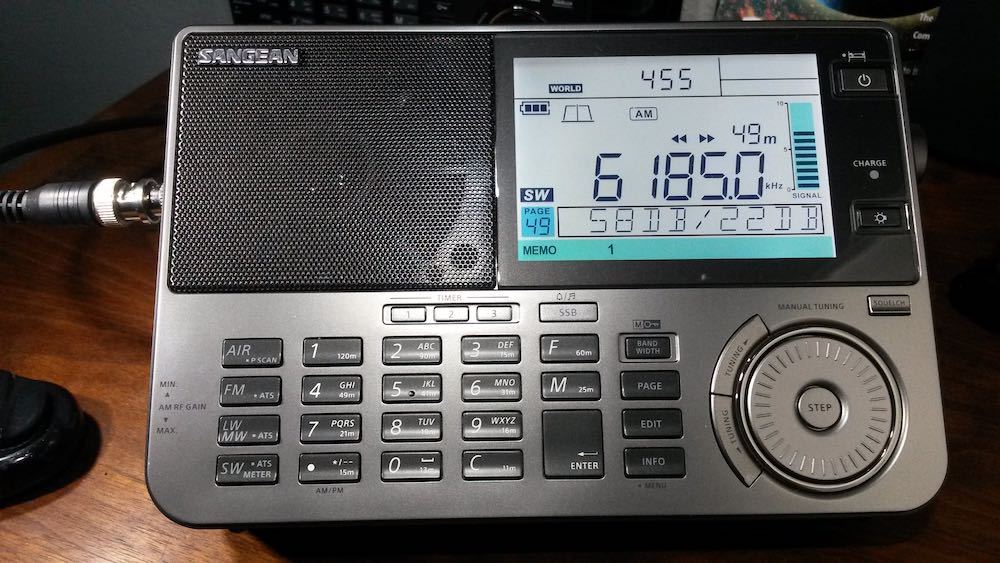

Sangean ATS-909X2 First Impressions

by DanH

A few hours spent tuning a new radio are enough to make me feel confident that I know most of the new features and how to use them. Then several days, weeks or months later I discover overlooked features and I figure out new ways to operate the radio. Sometimes I actually read the operating instructions again. Understand that I received my new Sangean ATS-909X2 only three days ago so this early report is hardly a comprehensive review nor was it intended as such. At this point I’m looking mostly at shortwave and medium wave performance.

My first experience with the new Sangean ATS-909X2 was online at the Amazon shopping site. On December 16, 2020 I pre-ordered the radio for US $459.99 (list price). The radio didn’t ship and the prices dropped a couple of times. Each time I cancelled the order before it shipped and ordered it again at the lower price. In the end I ordered my 909X2 for $297.95 and paid for it with credit card bonus points and a little more that I had on my Amazon gift card.

The 909X2 arrived on Friday afternoon, February 19. I devoted the first 24 hours to tuning around on SW and a little MW only. I deliberately made no videos at this time and devoted my radio time to exploring the bands. The latest addition to the ATS-909 series is a well thought out evolution of the radio and much more than a 909X with a cosmetic facelift. The 909X2 retains the excellent speaker sound of its predecessor, the tuning knob is unchanged from late production 909X, the solid build quality remains the same as does the general layout, performance, size and weight. SSB audio for the 909X2 remains at a lower level than for AM, like 909X. I don’t like having to turn the radio volume up for ECSS or SSB. Like 909X, the new radio excels with external antennas and is not easily overloaded by a lot of wire antenna.

Like 909X, 909X2 occupies an interesting niche in the portable multiband world. It is a little too large and heavy for a travel radio but over the years I have packed it many times in my carry-on bag. Sometimes I am willing to sacrifice extra clothes if it means bringing the best radio. These radios excel on a desk or radio room work station. The radio is big and powerful enough to provide top notch sound for all modes. Late at night I run mine with Sennheiser HD 280 Pro headphones. With 909X2 you get top performance in a small package. It is an over-used metaphor but think of a 1950 – 60’s communications receiver in a small package, plus VHF air band and FM. The speaker audio sounds better for broadcasts than many Amateur rigs.

There are many new features with the 909X2. Instead of charging NiMH batteries like Eneloop in series the 909X2 monitors each cell individually and identifies failing cells for you. SSB resolution is now selectable 10 – 20 Hz, auto-bandwidth control may be used on all bands except SSB on HF. There are many more memory slots available in three separate banks. The LCD has dimmer settings, soft muting is switchable for FM and the keyboard beeper may be shut off! Instead of hidden features the 909X2 has an INFO/MENU button for customizing your operating options.

The new bandwidth choices make a real improvement in LW, MW, SW, FM and VHF airband signal quality especially when adjusted in tandem with the audio tone control. Automatic bandwidth control selects the bandwidth that offers the best signal-to-noise ratio. Now I understand why the 9090X2 shortwave bandwidths are relatively closely-spaced: auto control shifts quickly between multiple bandwidths. Too much space between bandwidths would sound jarring. The auto bandwidth control is most useful during heavy fading and has improved my ability to copy words on poor AM broadcast signals. This feature does add an odd effect to fading signals: the audio tone quality will shift as different bandwidths are selected. This feature is not something that I would leave ON as a default for shortwave listening but it is definitely a welcome tool when needed.

MW performance is as good as the 909X but with improvements made possible with more bandwidth and memory slot availability. I found that 909X2 LW is generally better than 909X with fewer MW images. I am hearing substantially more LW beacons on 909X2. LW activity is very limited here on the US West Coast.

10 Hz SSB resolution means that ECSS is excellent on the 909X. I can tune a shortwave music broadcast on the 909X2 without warble. This was impossible with the 909X 40 Hz resolution.

The 909X sold near US $220 for most of the last five years with a few rare Amazon holiday sales at the $190 level. Then the prices jumped another $30 post-Covid 19, as did prices for other radios in this range.

Is 909X2 worth the additional money right now? I say yes! Mine is a keeper.

I do not believe that there will be significant improvements coming along any time soon. Sangean is a private Taiwanese company with its own factory located in PRC. 20 pre-production units delivered to Europe in January are not the same batch as the retail production units released by Sangean USA this month. Sangean USA has two of the pre-production units. They did not offer these for sale. The first retail production units arrived at Sangean USA in mid-February before the Lunar New Year. If there are significant changes for 909X2 we won’t see those radios for at least another 6 – 8 weeks. I can’t see much need for significant changes anyway.

Believe it or not I have been very busy with the Sangean ATS-909X2 and haven’t tried FM or VHF air band on it yet!

This video is a companion to my first impressions written here. Hearing and seeing video is hard to beat. SW and MW features are shown in real-life reception conditions. I test for the dreaded LCD/hand capacitance internal noise and have a look, listen and comparison for telescopic whip performance. And you will hear DX too, not just Brother Stair. You need to see and watch auto bandwidth control to believe it.

Wow! Thank you so much for sharing this, Dan. Very encouraging. We look forward to publishing your updates as you get to know the 909X2 even better!

Sangean ATS-909X2 Retailers:

- Amazon.com ($289.00) (affiliate link)

- Universal Radio ($319.95)

- Ham Radio Outlet ($359.96)

- Sangean Shop Retail Europe (€329.00)

- Sangean’s full dealer list

All prices are current at time of posting (22 Feb 2021).