Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Gary DeBock, who shares his extensive 2021 Ultralight Radio Shootout.

Many thanks to SWLing Post contributor, Gary DeBock, who shares his extensive 2021 Ultralight Radio Shootout.

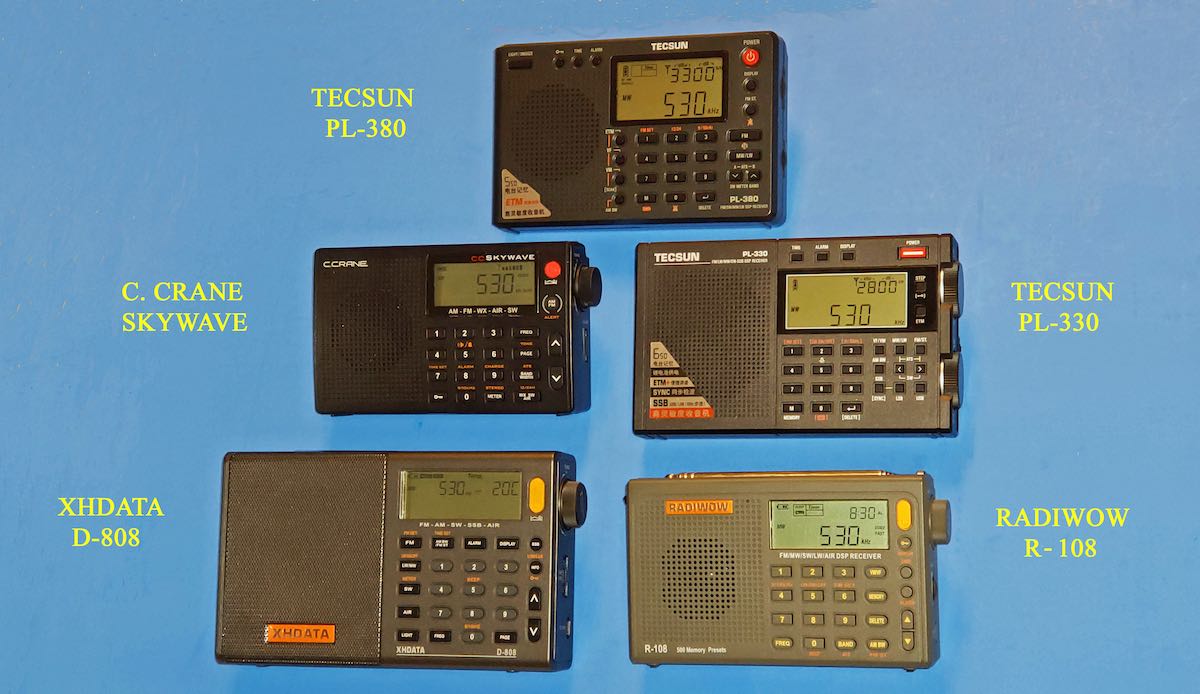

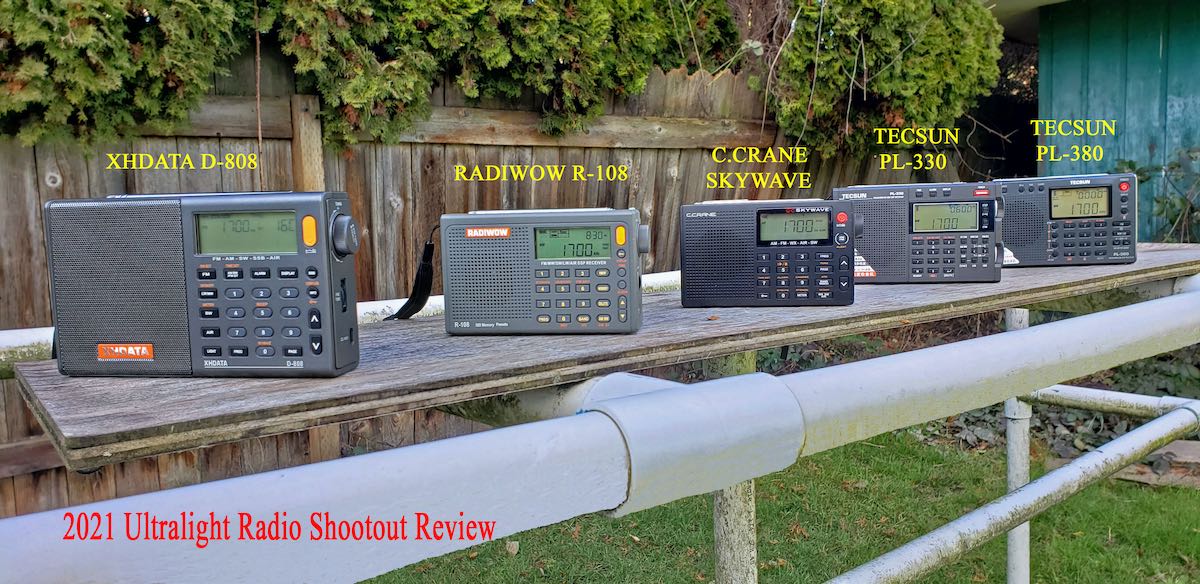

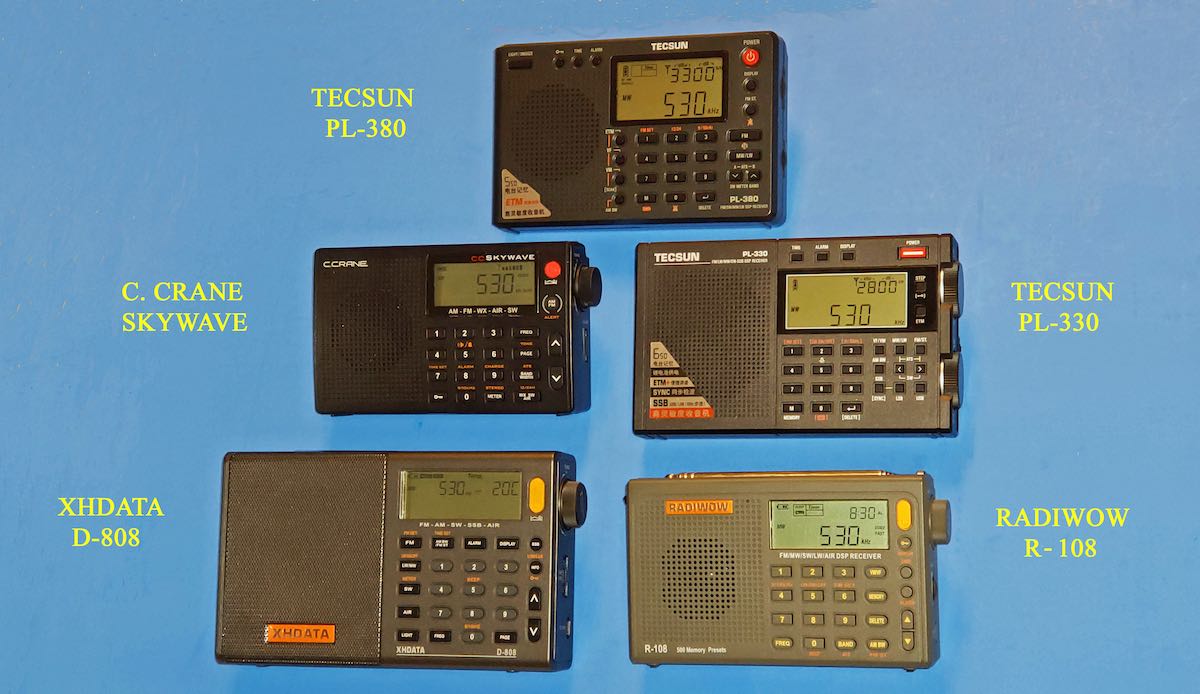

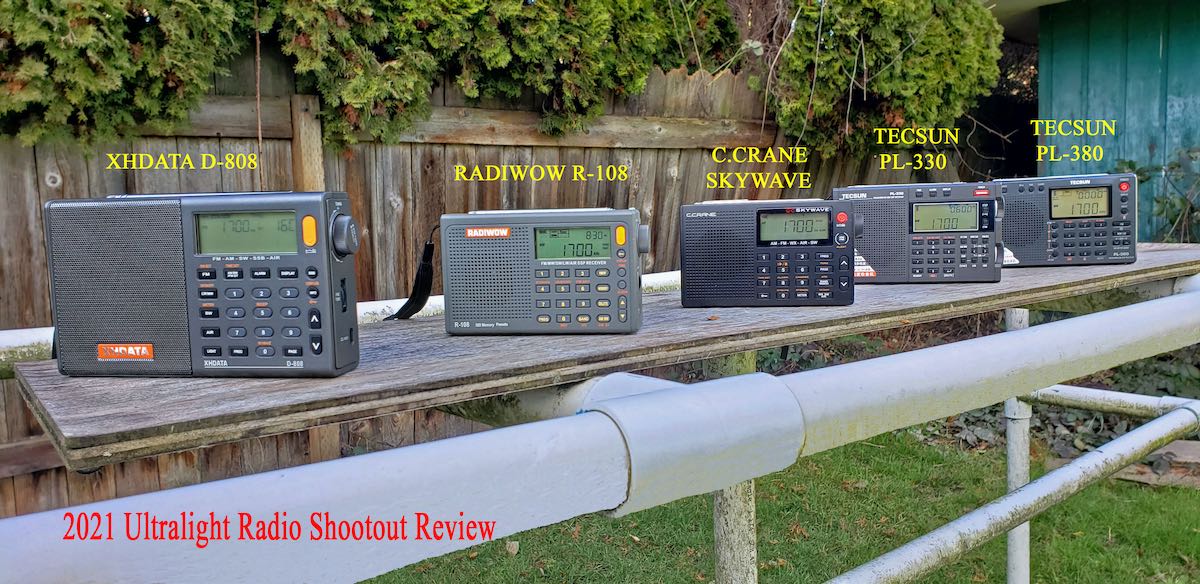

This is truly a deep dive featuring five popular ultralight portable radios and examining mediumwave, shortwave, FM, and AIR Band performance.

The review is an amazing 40 pages long! In order to display the entire review, click on the “Continue reading” link below.

2021 Ultralight Radio Shootout

Five Hot Little Portables Brighten Up the Pandemic

By Gary DeBock, Puyallup, WA, USA April 2021

Introduction The challenges and thrills of DXing with pocket radios have not only survived but thrived since the Ultralight Radio Boom in early 2008, resulting in a worldwide spread of the hobby niche group. Based upon the essential concepts of DXing skill, propagation knowledge and perseverance, the human factor is critical for success in pocket radio DXing, unlike with computer-controlled listening. The hobbyist either sinks or swims according to his own personal choices of DXing times, frequencies and recording decisions during limited propagation openings—all with the added challenge of depending on very basic equipment. DXing success or failure has never been more personal… but on the rare occasions when legendary DX is tracked down despite all of the multiple challenges, the thrill of success is truly exceptional—and based entirely upon one’s own DXing skill.

Ultralight Radio DXing has inspired spinoff fascination not only with portable antennas like the new Ferrite Sleeve Loops (FSL’s) but also with overseas travel DXing, enhanced transoceanic propagation at challenging sites like ocean side cliffs and Alaskan snowfields, as well as at isolated islands far out into the ocean. The extreme portability of advanced pocket radios and FSL antennas has truly allowed hobbyists to “go where no DXer has gone before,” experiencing breakthrough radio propagation, astonishing antenna performance and unforgettable hobby thrills. Among the radio hobby groups of 2021 it is continuing to be one of the most innovative and vibrant segments of the entire community.

The portable radio manufacturing industry has changed pretty dramatically over the past few years as much of the advanced technology used by foreign companies in their radio factories in China has been “appropriated” (to use a generous term) by new Chinese competitors. Without getting into the political ramifications of such behavior the obvious fact in the 2021 portable radio market is that all of the top competitors in this Shootout come from factories in China, and four of the five have Chinese name brands. For those who feel uneasy about this rampant copying of foreign technology the American-designed C. Crane Skywave is still available, although even it is still manufactured in Shenzhen, China—the nerve center of such copying.

Prior to purchasing any of these portables a DXer should assess his own hobby goals, especially whether transoceanic DXing will be part of the mission– in which case a full range of DSP filtering options is essential. Two of the China-brand models use only rechargeable 3.7v lithium type batteries with limited run time, which may not be a good choice for DXers who need long endurance out in the field. A hobbyist should also decide whether a strong manufacturer’s warranty is important. Quality control in some Chinese factories has been lacking, and some of the China-brand radio sellers offer only exchanges—after you pay to ship the defective model back to China. Purchasers should not assume that Western concepts of reliability and refunds apply in China, because in many cases they do not. When purchasing these radios a DXer should try to purchase through a reputable seller offering a meaningful warranty—preferably in their own home country.

One of the unique advantages of Ultralight Radio DXing is the opportunity to sample the latest in innovative technology at a very reasonable cost—and the five pocket radio models chosen for this review include some second-generation DSP chip models with astonishing capabilities. Whether your interest is in domestic or split-frequency AM-DXing, FM, Longwave or Shortwave, the pocket radio manufacturers have designed a breakthrough model for you—and you can try out any (or all) of them at a cost far less than that of a single table receiver. So get ready for some exciting introductions… and an even more exciting four band DXing competition!

Continue reading →

Continue reading →