As I’ve mentioned many times here on the SWLing Post, I’m something of a “content DXer.”

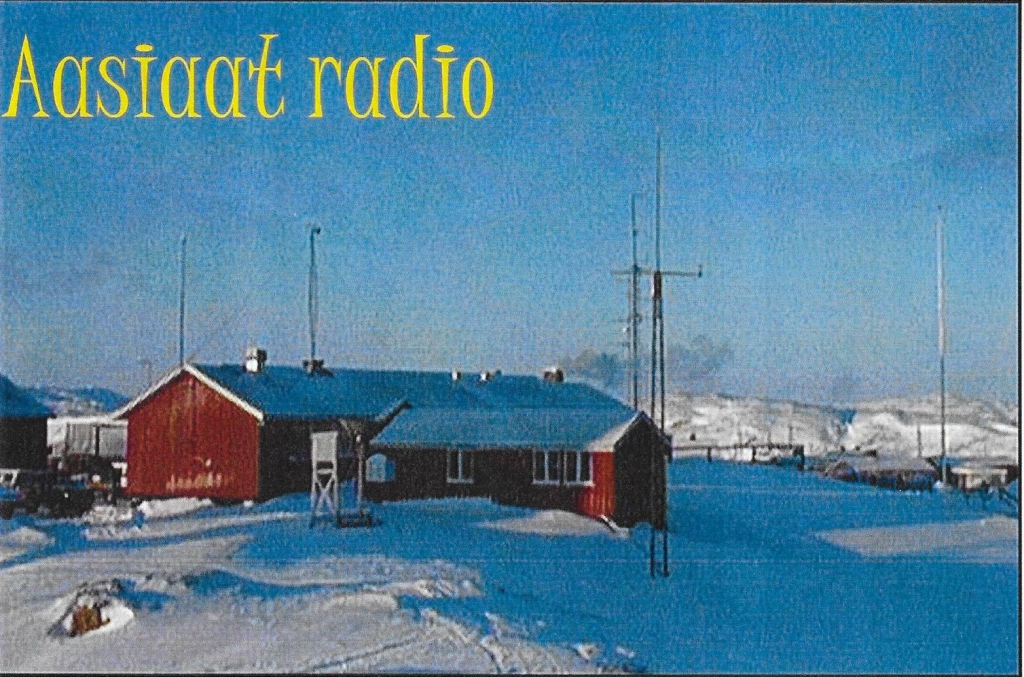

Clearly, I enjoy chasing obscure programming––news, documentaries, music, variety shows, anything the broadcasting world has to offer. Even though my favorite medium for doing this has been shortwave radio, these days, I often turn to Wi-Fi or over-the-internet radio. Wi-Fi radio offers the discerning listener the ability to track down fascinating regional content from every corner of the globe––content never actually intended for an international audience.

If you, too, like the chase, The Worldwide Listening Guide (WWLG) will be your go-to, and this recent edition––the tenth!––is the latest in a long line of handy volumes that help the listener catch what’s out there, noting that with each passing year there’s more content to catch.

Cornucopia of content

The variety of content from online broadcasters today is surely orders of magnitude more than any one individual has ever had via over-the-air (OTA) radio sources.

Though my WiFi radio offers an easy and reliable way to “tune” to online content––both real-time station streams and on-demand podcasts––the content discovery part is actually quite difficult. I liken it to browsing a large public library looking for a new and interesting book to read, but without the guidance of a librarian. The options are so plentiful that even with superb indexing and organization, one simply doesn’t know where to begin.

On the other hand––and I’m speaking from very recent experience here––if you find a good local independent bookstore, you might actually discover more meaningful titles because the bookstore selections are curated by both the proprietor and the local community.

With this analogy in mind, The Worldwide Listening Guide is essentially my local bookstore for online content and programming.

I recently received a review copy of the new 10th Edition of the Worldwide Listening Guide by John Figliozzi and, as always, I enjoyed reading it from cover to cover.

The WWLG speaks to the types of programming I enjoy as an SWL because the author, John Figliozzi, is a devoted shortwave radio and international broadcasting enthusiast.

And while the bulk of the WWLG is a detailed and beautifully organized programming guide, it’s also so much more…

“The Many Platforms of radio”

As I’ve so often said, the WWLG is a unique guide; there’s nothing quite like it on the market because it truly takes a deep dive into the world of broadcasting and content delivery both from a technology and programming point of view.

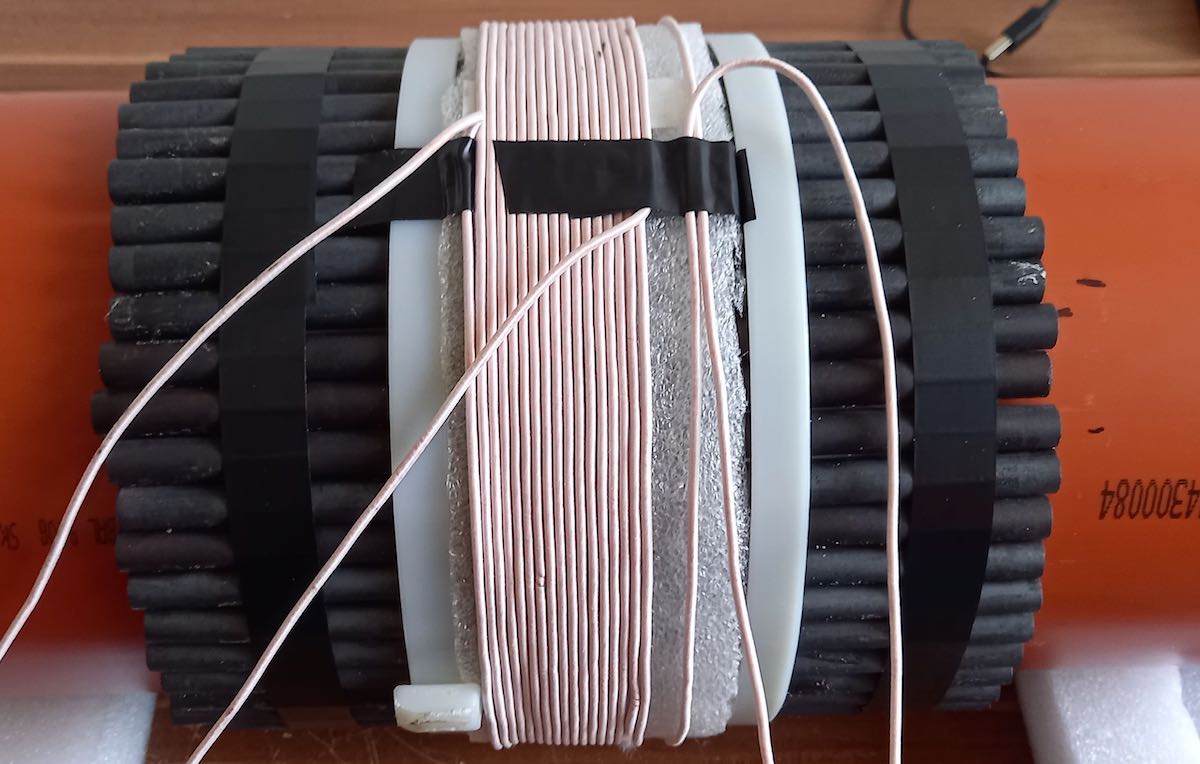

Each media delivery platform, whether on AM, Shortwave, FM, Satellite Radio, Internet (WiFi Radio), and Podcasting, has a dedicated section in the book where Figliozzi explores each in detail. He also speaks to the state of each platform both from the broadcaster’s and the listener’s perspective.

Indeed, each chapter dedicated to these topics very much reminds me of the old Passport to Worldband Radio that I first picked up in the 1990s. The WWLG serves as a primer, but also speaks to the health and potential longevity of each platform.

I appreciate the fact that Figliozzi also addresses the nuts-and-bolts side of both over-the-air and online broadcasting. For while I’d like to think that I’m reasonably knowledgeable about the world of radio, I find I always discover something new in each edition.

There’s a surprising amount of information packed into this slim, spiral-bound volume. The Worldwide Listening Guide is enough to keep even a seasoned content DXer happy for years…or at least, until the latest edition comes out!

In short? The WWLG is a bargain for all it offers, and I highly recommend it.

The 10th edition of The Worldwide Listening Guide can be purchased here:

Note that at time of posting copies of the WWLG can be pre-ordered at Universal Radio. Amazon.com will soon have links to purchase the 10th edition when they’re in inventory. I assume the W5YI group will also have the 10th edition available for purchase soon!